How London's Menswear Broke the Mold

An oral history of the city’s industry-disrupting talent, as told by its designers.

You are reading your free article for this month.

Members-only

Every fashion capital would have you believe it’s the best one. Paris has the prestige. Milan has its own household names and the backing of an extraordinary textiles industry. And New York, while checkered in its fashion week history, has produced undeniable stars.

But few would argue with the fact that London is the home of innovation. Its combination of esteemed fashion colleges, underground cultures and proximity to continental Europe has created a melting pot for creatives. And while it’s not without its flaws — particularly, its tendency to launch untested designers into brands before they are ready — the city’s creatives have been at the forefront of all of the disruptive innovations in menswear over the last two decades, from luxury sportswear to the rise of gender-neutral design.

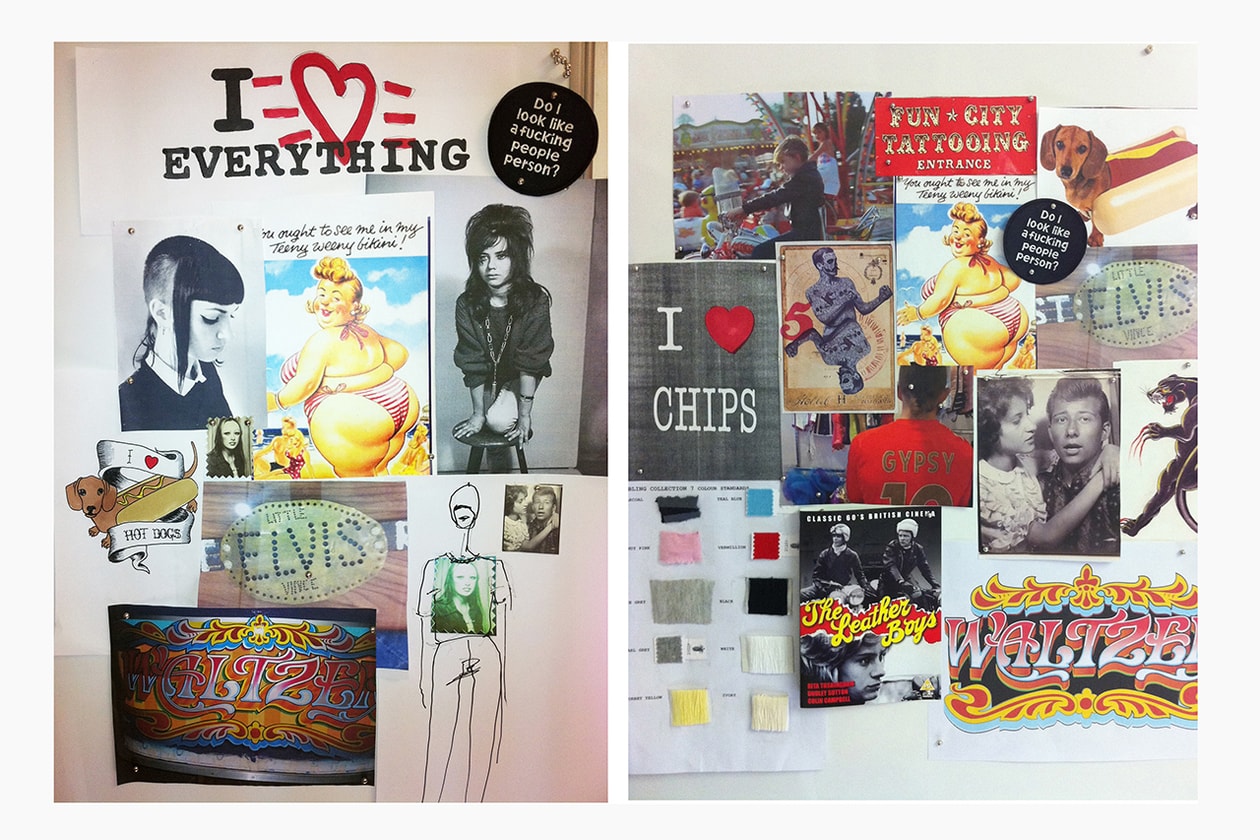

Fashion East — the talent incubator scheme set up by Lulu Kennedy, which celebrates its twentieth anniversary this year – can lay claim to a large part of the praise for that. Designers selected for support receive sponsorship to manufacture and present their collections, receive industry mentorship and, perhaps most importantly, access financial support that allows them to develop their work without external commercial pressure.

“There was a lot of snobbery around: a sense that sportswear and tracksuits can’t be luxury fashion.”

It’s a scheme that has no counterpart in any other fashion capital and has met with considerable success. The roster of designers who received sponsorship and support from Fashion East reads like a roll-call of British design talent: Kim Jones, Craig Green, JW Anderson, Grace Wales Bonner and Martine Rose included.

As another season of London Fashion Week begins, and Fashion East enters its third decade, HYPEBEAST asked its most notable alumni — who span age, gender and background — to recount each of their rises.

On meeting Lulu Kennedy, and getting into Fashion East:

Cozette McCreery, SIBLING: I actually started off by doing the door at Fashion East shows. It must have been around 2005, or 2006. I used to work the door at [legendary East London club night] Boombox, so people started bringing me in to help them at their shows. We all sort of knew of Lulu: she was always around.

Martine Rose: When I did my first fashion installation in 2007, I invited everyone I knew, which was mates, and mates of mates. Lulu came, and she invited me to participate in Fashion East off the back of it. I remember her sprinting down the road, which I was charmed at — I was no-one, and she was running to see my weird installation like it was a Chanel show.

Christopher Shannon: Weirdly, I wasn’t approached by Lulu, as she was away. It was someone at Topman who asked me, and then you had to get voted in, in the beginning of a very X Factor-esque scenario. It was Mandi Lennard and Sarah Andelman from colette, and they liked my work, and then I got the call.

Aitor Throup: For me, it was through [fashion critic] Sarah Mower, who had introduced me — it was towards the end of 2006, and they invited me to be involved in January 2007.

Carri Munden, Cassette Playa: I used to go to Fashion East shows as a student, as I knew Lulu from the club scene in the mid ’00s: nights like Kashpoint and Super Super. She was always just so sweet and kind. I started making collections after I graduated, and I contacted Lulu myself.

Charles Jeffrey: Mine was a funny story. I was doing my MA at [Central] Saint Martins in 2017, and they do a big space where they have all of the students work on display. And I had just been told by one of my teachers, “I don’t think you’re a designer, you won’t ever get a job in a house with this portfolio, maybe you should make weird objects and see how that goes, or continue to do club nights.” Then Lulu asked if I wanted to do Fashion East.

Eden Loweth, ART SCHOOL: I was interning for Grace [Wales Bonner] just as she got into Fashion East. I met her and she said that she needed some help, and I ended up working with Grace for the three years that I was at uni. It completely changed my life, as I met Lulu through that. It was so surreal because people like me don’t get these opportunities — I had a very sheltered, home-schooled upbringing. But Lulu believed in me through everything. She’s been a mother to me. Probably the single-most important person in my adult life.

“It was all quite chaotic: I was appearing in Vogue, but I didn’t have any money.”

On London:

Cozette McCreery, SIBLING: Because of the way East London was [in the late noughties], you could always find people. You would go to the Bricklayers Arms, or the George and Dragon, or even the Joiner’s Arms at the time and you would meet people like Lulu or Louise Gray or Gareth Pugh or Giles [Deacon] or Jonathan Saunders. It was quite a mix.

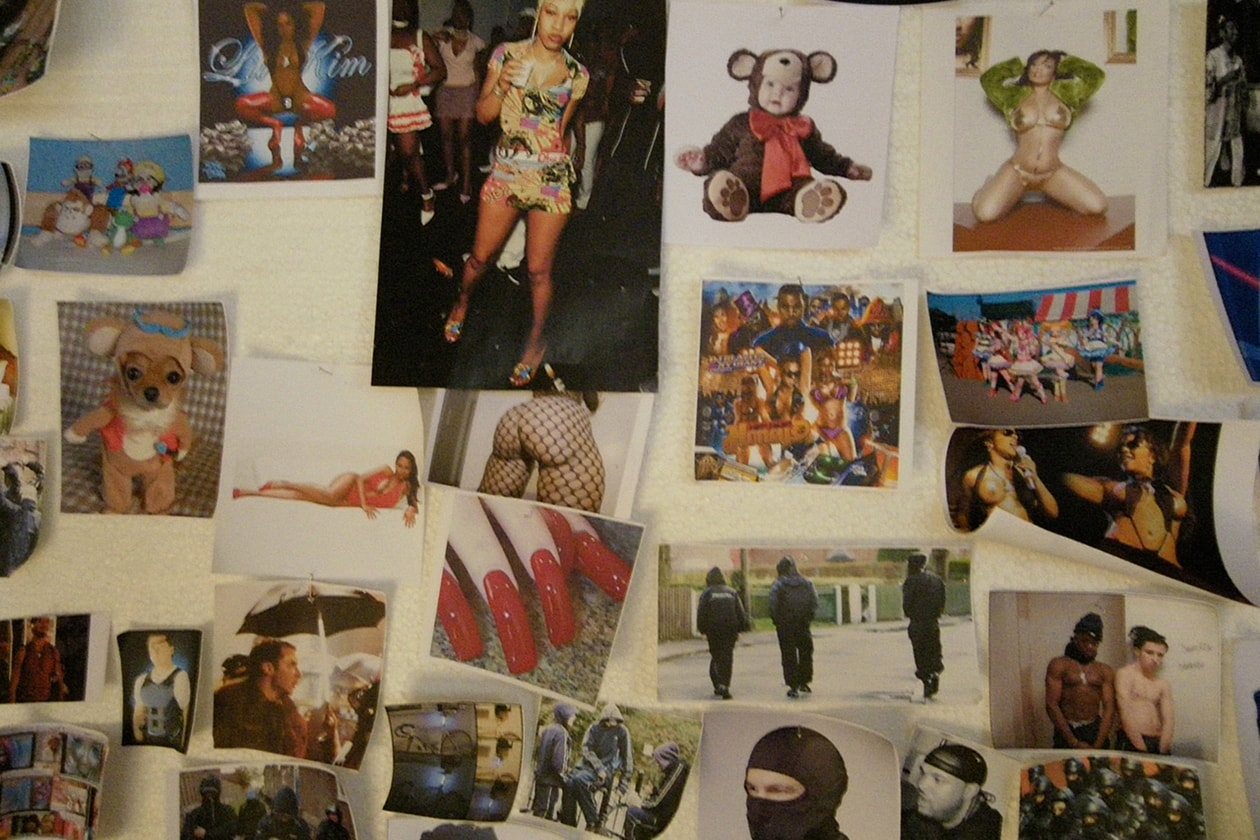

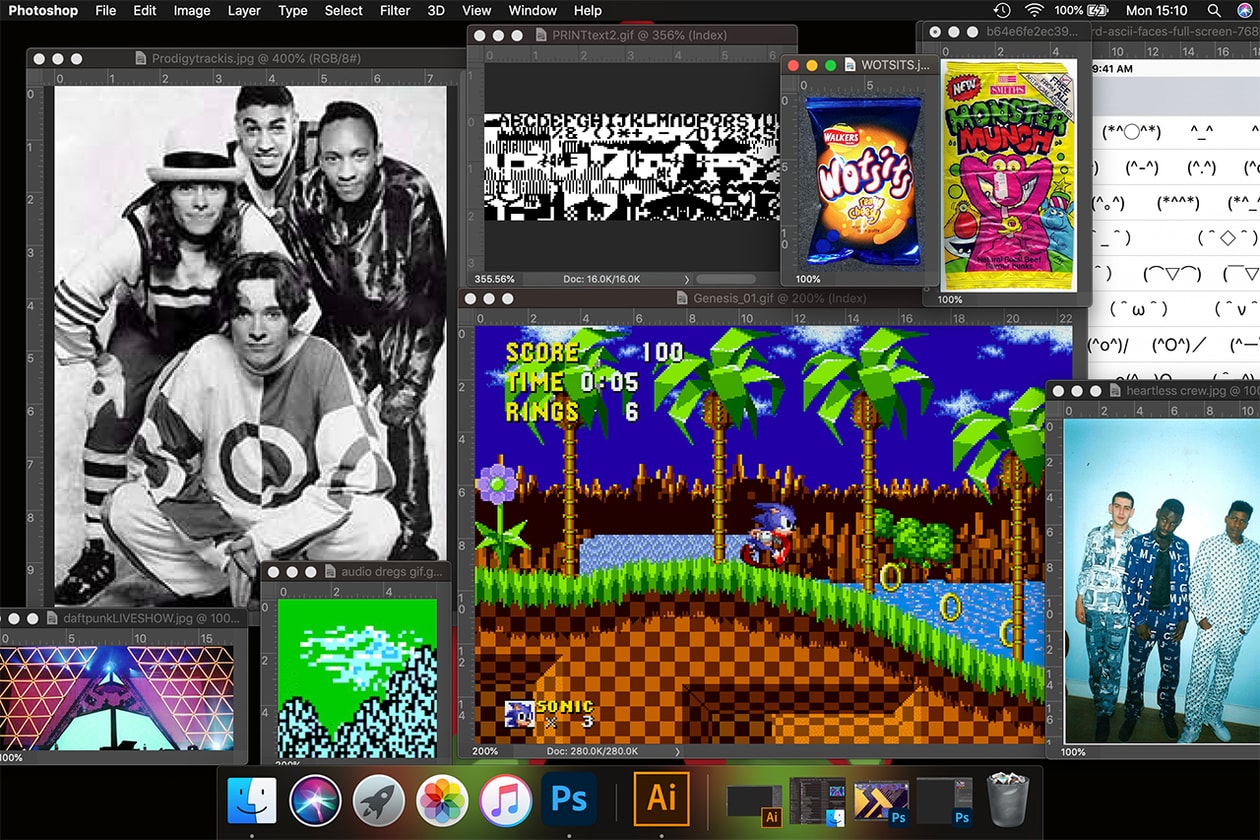

Nasir Mazhar: There was loads happening in East London. It hadn’t been so gentrified yet. There was a lot of going out. And there wasn’t this external interruption from social media: if you were at certain places, you were there because you knew about it through your friends, it wasn’t because you’d seen it on Instagram.

Dr. Noki: I was right in the thick of all these different crews from London, coming from Camden, Soho, Portobello. And it was the Shoreditch days proper: off my head, wrecked out my tits, surrounded by more people off their tits, wrecked and rave going toxic.

Martine Rose: It was obviously alternative, but all of those places were communities in the truest sense of the word. I considered it the creative hub of the fashion community: there were a lot of parties, but not in a slacker way, in an essential way. Culture is fashion and fashion is culture. You can’t do one without the other.

Grace Wales Bonner: At the start I wasn’t really acknowledging London within my work. Quite intentionally, I wanted it to feel like it could have come from anywhere. I look at things from an Afro-Atlantic perspective. It had to have a global spirit.

Astrid Andersen: It was still such an inspiring place when I was coming up in 2011. It was Nasir [Mazhar], Christopher Shannon, Cottweiler, Shaun Samson and me. It felt like we had a place because now people were watching and listening and we were being noticed. We still didn’t know what we were doing, but that was the beauty of it and what made it so inspiring. No one really knew exactly where it was going.

On the menswear community:

Thom Murphy, New Power Studio: By and large the London scene is quite friendly. Most of the people kind of know each other, or had been to school together or used to hang out in East London. So I think there’s always a certain amount of friendliness, but there has to be competitiveness as well.

Martine Rose: It wasn’t really competitive for me. Honestly, it was like a family. Menswear is different to womenswear, as it’s so much smaller – there was a tiny cohort of menswear designers. And menswear designers were outsiders in the fashion community, so we naturally clubbed together in that way.

Cozette McCreery, SIBLING: When you do menswear, you kind of feel like the underdog. You don’t get the sponsorship that womenswear does, which is insane. There’s this definite gender divide when it comes to support from big companies. You always feel like you’re fighting your own corner.

Craig Green: I became really good friends with all the designers I showed alongside. Everyone supported each other in London at the time because everyone was in the same boat. No one really had businesses. We were all just starting out and trying things out together. Some of them I’m still friends with now, and they’re relationships I’ve built over that time.

Astrid Andersen: I started doing the shows at the same time as Craig [Green] and that’s one of the most profound relationships I have within fashion now. We had so many shared moments where we were both a mess, but also the happiest we’d ever been.

James Theseus Buck, Rottingdean Bazaar: It was different for us, as we were rarely in London. Most of the time designers at Fashion East hang out outside of their work or visit each other’s studios. But we had a more distant experience.

Nasir Mazhar: I always felt like a bit of a backstreet designer. I hadn’t really come up the same way, I was a bit of an outsider. I was previously a hairdresser, so I didn’t know loads of fashion people. I just didn’t feel proper, I didn’t feel like a real designer. I don’t think I did for years.

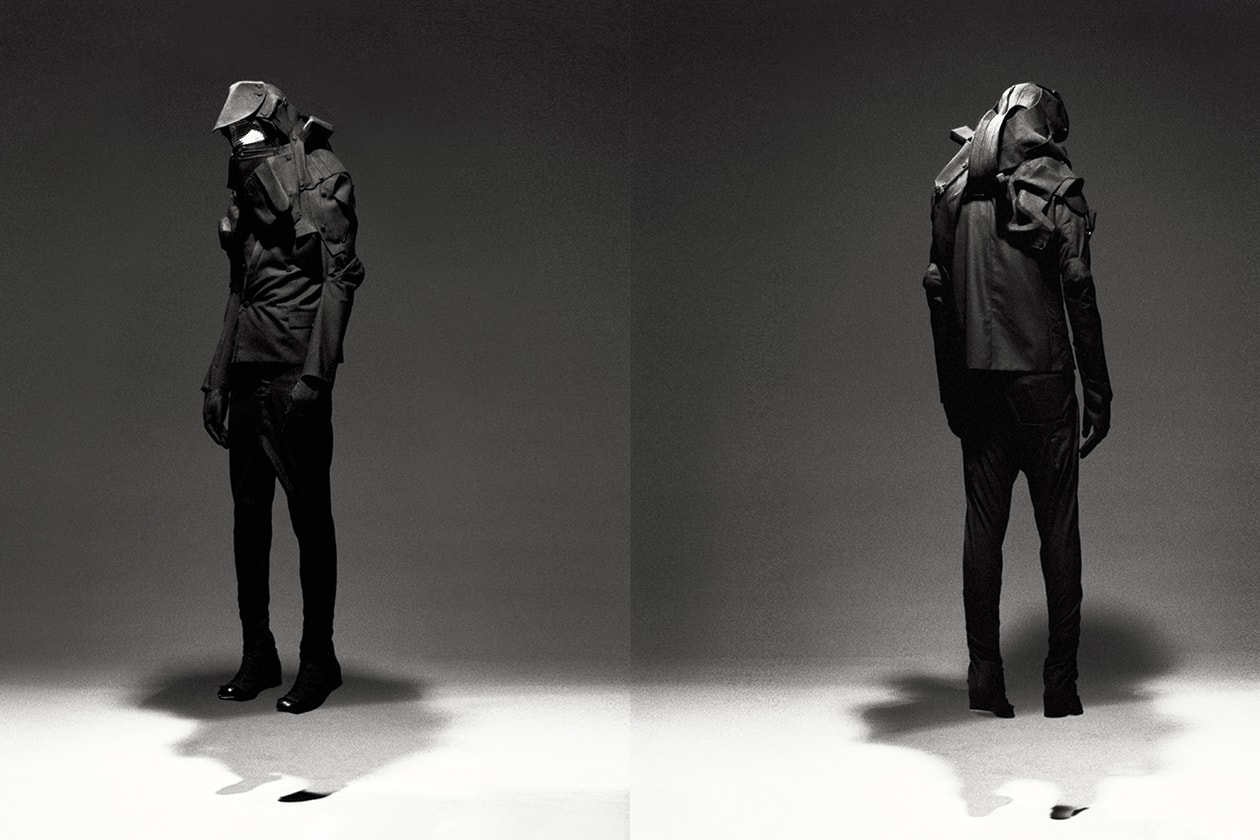

Aitor Throup: I felt like the odd one out. Like I was trying to say something that had a narrative that was beyond — I think all good fashion has a narrative that goes beyond fashion, obviously — but, it certainly felt like it was a contrast with some of the other things that were around at the time.

Grace Wales Bonner: I had my head down quite a lot, and I was really in my own world. I wasn’t really looking at what was going on around me.

Charles Jeffrey: I started at the same time as Grace, and we always got on really well. She feels like a little sister. It felt like we were two opposite ends of the spectrum: she had her very together, polished, heavenly, intellectual collections and mine were these grotty, crazy, drunk, bedraggled creatures. It was nice to have that contrast.

On their first presentations:

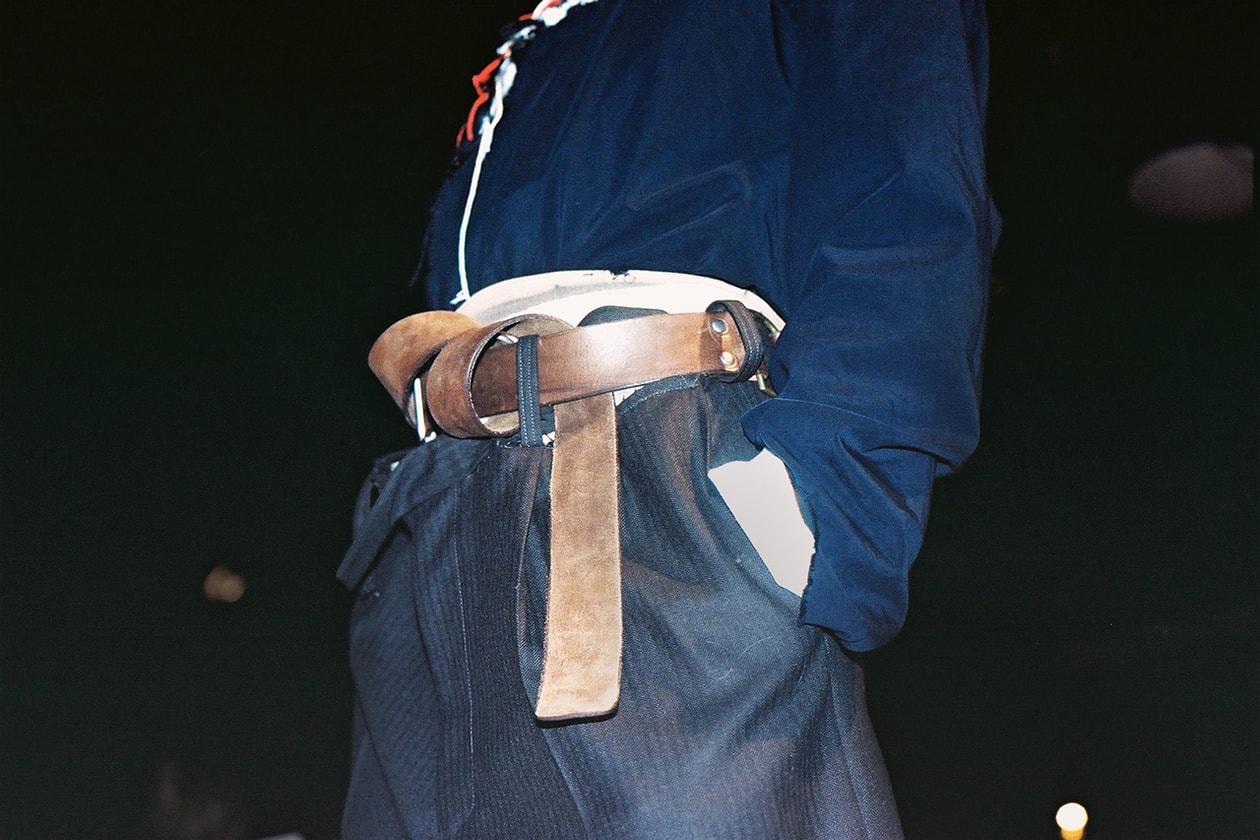

Craig Green: It was a big shock. I think we were underprepared for how chaotic it could be. We lost some important elements, and we found them two minutes before the show started. Without them it would have been a big disaster.

Cozette McCreery, SIBLING: It was all so ad-hoc. We got all our friends together, the George sorted out alcohol, Bistrotheque did the food, Rob Meyers photographed a whole group of friends from my Myspace feed – back when that was a thing. I remember it being incredibly busy, which was a total bonus. It did all look professional, and then I think we all went to the pub afterwards.Then that evening, BEAMS Japan came up and said “I want to buy this.”

Nasir Mazhar: The first time I made clothes, for these presentations, was the first time I’d ever made a garment. I’d never made anything other than headwear before. I suppose that’s what was exciting about it – all these new people coming up with new ways to show things and show different things, compared to just conventional maxi-dresses or whatever people do.

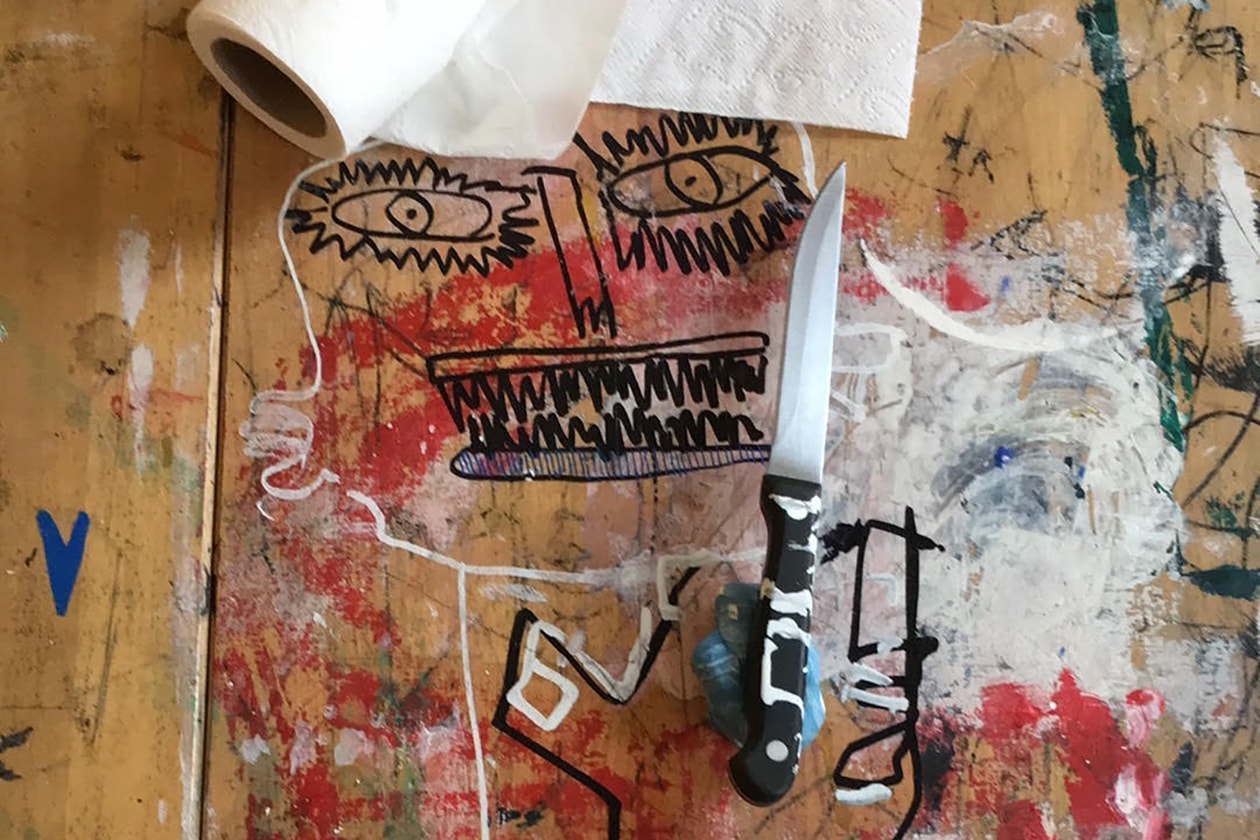

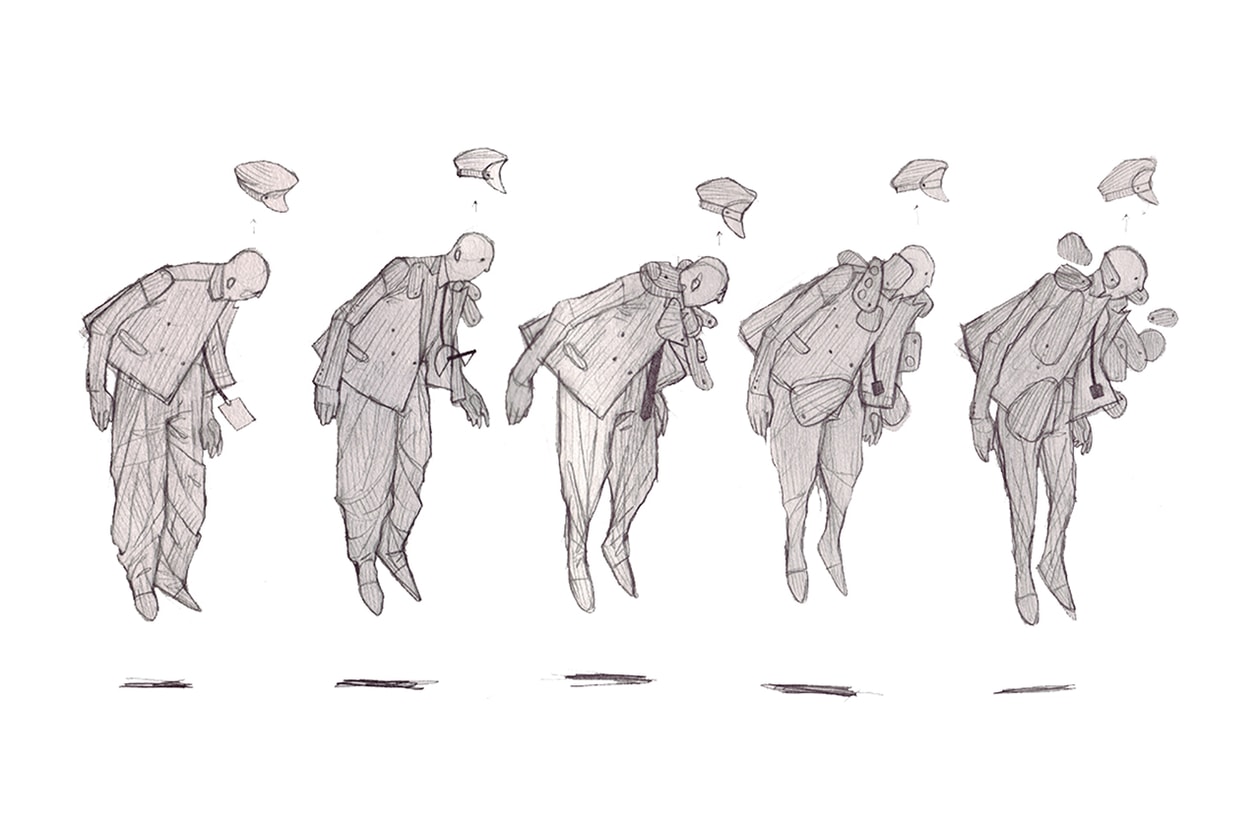

Aitor Throup: I didn’t want to do a catwalk, I knew from the very beginning that I wasn’t interested in that, I wanted to install sculptures and treat it more like an art gallery and be very narrative-driven. She gave me full reign and I ended up making these two suits, suspending them. There was a concept that each suit was made from these miniature sculptures that I’d made, and the tiny little patterns that I’d extracted from these sculptures were also exhibited and suspended. We told a full story.

Thom Murphy, New Power Studio: We did one presentation with a mobility scooter. I had this idea of using one as part of the presentation, so we had this guy drive that down the catwalk and that was hilarious. I’d seen a reference and thought would be great, then the assistants would question it and I’d chicken out a bit. But it had to work because it was such a daft idea.

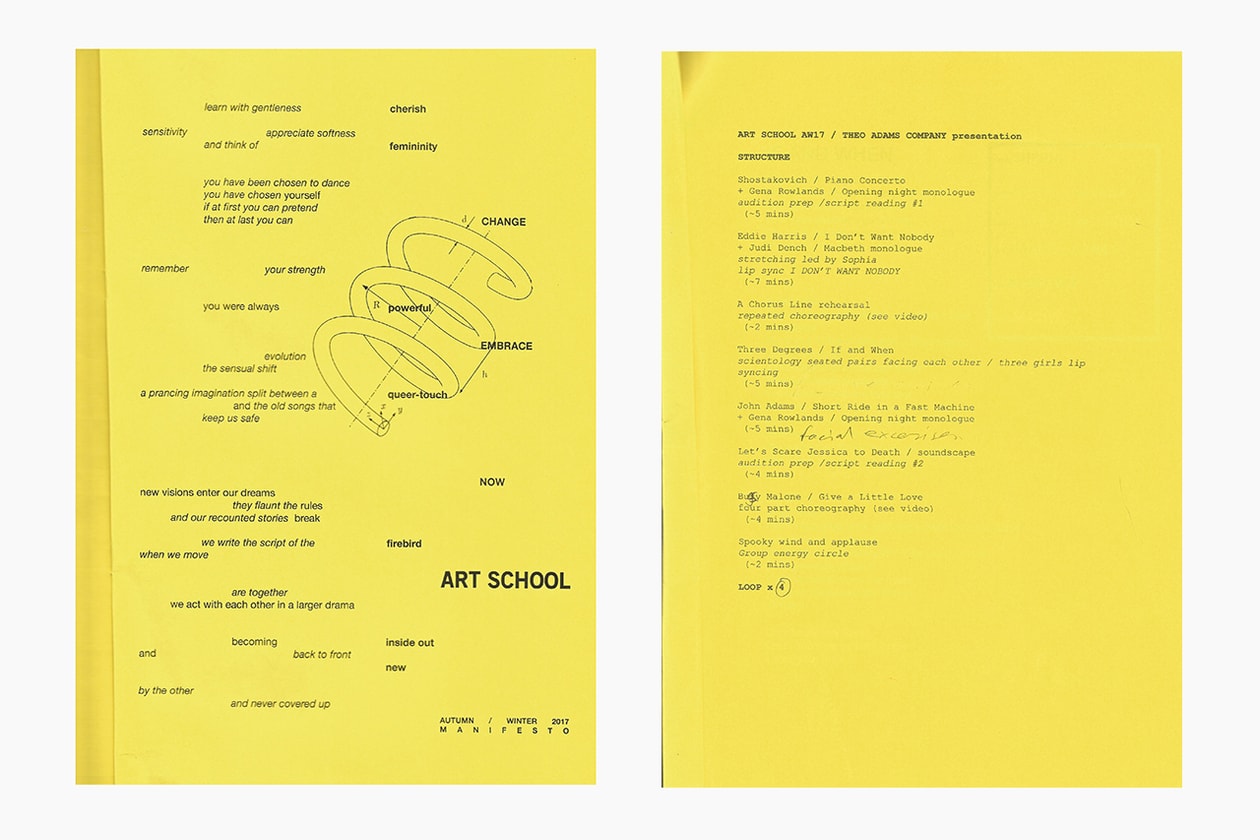

Eden Loweth, ART SCHOOL: We did a presentation, which I don’t usually like as a format – as a queer person I wanted the full fantasy of a catwalk. But we found this space in the old Selfridges hotel, and got together a group of people for a performance. We planned it in four hours the night before the show, and they stayed up all night to memorize it. It was so mental. I thought I’d f*cked it. But then Selfridges wanted to buy the whole collection there and then, so it blew up immediately.

Luke Brooks, Rottingdean Bazaar: There was less pressure for us, because of the way we were showing: we did a series of badges which we presented in a shop space. They had things in them like balloons, pubes, fag butts. So we were kind of like an add-on to Fashion East.

On disrupting the system:

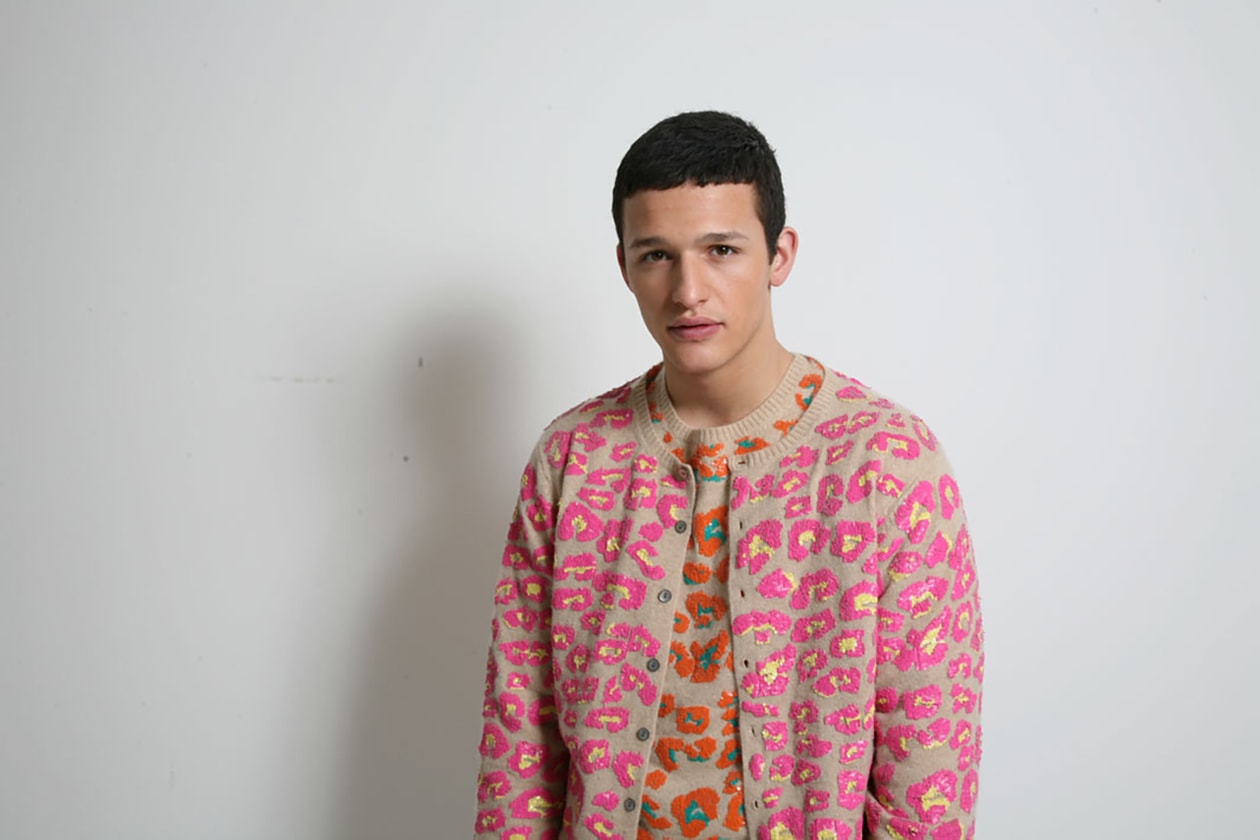

Christopher Shannon: I remember my first show feeling really rebellious, because I’d never seen Reebok Classics on the runway before. I think there was a lot of snobbery around from the press. At the time it did feel quite controversial, because it didn’t look like what anyone else was doing in London or Paris. There was definitely a sense that sportswear and tracksuits can’t be luxury fashion. It wasn’t until around my fourth show that everybody started jumping on the bandwagon.

Carri Munden, Cassette Playa: I was working with Thom [Murphy] on the casting for our show. We were doing street casting, which wasn’t really a thing at the time, but it was really important to me. The models who were at agencies at the time I didn’t connect with and I wanted to show a different kind of masculinity, I hate that word and I think it’s overused, and I wasn’t thinking in those terms at the time, but diversity… whether that’s racially or a body type. That was a really big part of that show.

Christopher Shannon: You would not believe how white the modeling agencies were at that point, it seems insane now. That took ages to change.

Eden Loweth, ART SCHOOL: People were very shocked by having so many trans models in our show. Even now, it’s still a conversation that we’re having to talk about. It shows how, at the time, nobody really understood why we were doing this and I think for the first time, a lot of people felt that what we were trying to didn’t look like tokenism — it was integral to the way the brand was developing and that’s what interested people.

Grace Wales Bonner: My collections were reacting to what I saw as a lack within fashion in general: I was trying to create space for a more nuanced representation of Black culture within fashion, that was less stereotypical and repetitive. I wanted to show something more sophisticated.

Aitor Throup: Systemic racism has been a running narrative throughout my work. Through my own experiences of being an immigrant in two different countries in my formative years, going from Argentina to Madrid, spending five years there, then from Madrid to England, where I faced that much more so. It affected me quite deeply. There was a tension in the air for sure that seemed connected to these themes, which funnily enough seems that again a relevant consistent topic in the news as of late.

On business:

Christopher Shannon: I picked up a lot of stores quite fast and, in a way, I looked quite amateurish in those stores. We just weren’t set up to sit next to Margiela and Dries Van Noten.

Grace Wales Bonner: It wasn’t about commerciality, or having a brand, at first. I was thinking about it more as an intellectual study.

Astrid Andersen: I remember trying to decide whether to price something at €40 or €100. I didn’t know what I was doing. It’s kind of funny looking back on it now. We still talk about those times now.

Thom Murphy, New Power Studio: It can be a great thing to start with a show first and then get a business together afterwards – and it’s a very London thing, because there’s lots of opportunities to do that. But you kind of do another show, do another show, do another show and then you haven’t really got much business underneath it really. It’s OK and it can work, but it also can not. You’re always catching up to do the next show.

Charles Jeffrey: It was all quite chaotic. I was appearing in Vogue, but I didn’t have any money.

Eden Loweth, ART SCHOOL: You’re often very young, and you’re in the public eye, and that can be especially difficult if you’re a queer person like me or Charles.

Christopher Shannon: So many designers were doing these platforms and then ended up in loads of debt three seasons later with mental health issues. It’s not without its huge risks.

Dr Noki: I’m not really fashion-built; I’m not very good at being around the fashion industry. I did try, but it was going nowhere. Press was drying up. It didn’t really feel like I could go further with it, so I kind of pulled away and started working on my art again.

Craig Green: It was a bit of a friends and family operation for me. Everyone got involved. I don’t know how much we spent, but the first collection cost next to nothing. The sculptures were made out of B&Q fences that we smashed up and painted, and most of the clothes were made out of calico that we’d washed and painted. It was really make-do. I think it’s almost amazing if you look back that you can do something with nothing and with the right people.

Grace Wales Bonner: What was special about Fashion East is that it gave me space to develop my ideas. It gave me time to explore my design identity. In a way, that innocence was quite liberating. And eventually it did lead me to find things that were commercially successful.

Cozette McCreery, SIBLING: It’s like a finishing school, really.

Reporting contributed by Jack Stanley, Eric Brain, and Tayler Willson.