"You Can't Stop the Wheel": The Relentless Reality of Running a Label

For many designers, having your name on the label is the dream. Until you actually do it.

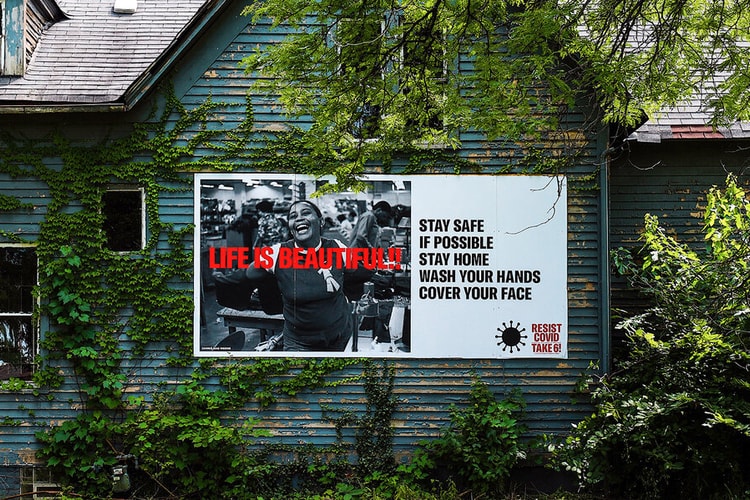

What do you know about “the system”? If you’ve read anything about fashion in the past couple of years, probably just enough to know that it’s bad. It needs fixing, beating or pulling out of its existential crisis, depending on what you read. “The system” has become fashion’s equivalent of “the Man”: an indiscriminate term used to gesture towards a host of separate ills within the industry. What’s clearer is that COVID-19 — and the lockdowns that have followed it — has laid these problems bare. In May, the British Fashion Council and the Council of Fashion Designers of America released a joint statement, explaining that the virus had shown that “the fashion system must change.”

The pandemic has already taken its toll on emerging fashion brands. In June, the New York-based label Sies Marjan – which had been applauded by the press and stocked by the world’s most esteemed luxury retailers – announced that it would be closing permanently. Sadly, it’s a near-certainty that many more brands will follow in its footsteps. But while the chaos of 2020 has undoubtedly accelerated the demise of several labels, it has only exacerbated a pre-existing problem at the heart of the “broken system”: the fashion industry’s relentless search for novelty, which has created a conveyor belt of “new names to know.”

While some manage to transform that initial hype into a viable business – Heron Preston, Jonathan Anderson and Simon Porte Jacquemus, for instance – many more find themselves cast adrift, as the industry moves on to its latest name, often in spite of their inexperience and the untested commercial reaction to their work. And despite widely-publicized initiatives by retailers and industry bodies to offer (frequently unqualified) “support” to emergent brands, there’s a long line of widely hyped brands that have quietly vanished from the runway schedules in New York and London: Tim Coppens, Meadham Kirchhoff, Thomas Tait, and Orley, to name a few. So what happens after that? Is there life after closing your label?

“Ironically, as soon as we started to win awards, it all started to go downhill.”

It was during the 2008 recession that Agi Mdumulla and Sam Cotton founded their brand, Agi & Sam. “We couldn’t get jobs anywhere else, basically,” says Cotton. “So we thought, f*ck it. Let’s just do something ourselves, and have some fun with it.” The two had met while interning at Alexander McQueen in London and decided to collaborate shortly after. “I guess we were quite naive,” says Mdumulla. “We definitely didn’t go into it with a plan or expecting that we’d make a load of money. We just thought our points of view were strong enough that people might be interested in it.” Though both had creative backgrounds, neither had much experience in business. “Nothing had set us up to understand how to run a brand,” Cotton says. “I’d picked up a few things from working for other designers. But in general, if we didn’t know how to do something, we just had to Google it.”

Their ascent was swift; by the time they produced their fourth collection, in 2012, they had generated enough industry noise to attract sponsorship from Topman. It allowed them to show on the runway at London Fashion Week for the first time, as part of the MAN fashion showcase. The British press quickly touted them as “the buzz of the men’s fashion scene,” and store buyers followed soon after. “After that first show, we were on cloud nine for about two months,” says Mdumulla. “The euphoria of it all being received so well – it felt like we were suddenly moving up the rungs of the ladder. And the business side of it wasn’t so daunting at the start – we just figured it out as we went along, and the orders from stores were so small that it was manageable.”

By 2014, the pair had won the Emerging Talent category at the British Fashion Awards, and been named as two of GQ magazine’s Men of the Year. Their fall collection of that year proved to be a turning point: inspired by Mdumulla’s Masai heritage, it was widely agreed to be their best yet. Overnight, their orders quadrupled, and they found themselves carried by prestige retailers including Barneys, MATCHESFASHION and Browns. “For me, that’s when it all went a bit mental,” says Mdumulla. “Ironically, as soon as we started to win awards, it all started to go downhill.”

Suddenly, the pair were elevated to a level of fame within the industry that they hadn’t anticipated – or even wanted. “I didn’t care about my face being on anything,” says Cotton. “Neither of us did. If anything, that was the part of the job we hated the most.” Though both of them are congenial and charismatic in person, they struggled with having to promote themselves. Mdumulla recalls leaving the GQ event where they had won their award, to cry outside on the phone to his father. “I had such a strong imposter syndrome,” he says, “and I really struggled with the attention. I never knew whether people were being fake and what they wanted from us.”

They found, too, that their growing stature within the industry ramped up the expectations from retailers. “Before that, we always had felt like we were in control,” says Mdumulla. “But the stores stopped making allowances for any mistakes we’d make or any growing pains. The pressure really started to mount.” Not only that, but the industry was demanding constant growth from the pair, instead of allowing them the time to nurture their ideas. “I remember saying to Agi that what we had done with the Fall 2014 collection, that was us,” says Cotton. “And there was no reason why we couldn’t keep pushing and evolving that. But everybody was telling us they wanted newness. And we were so scared that it would seem like we were repeating ourselves.”

“You’d end up sitting on thousands of dollars of unsold stock. But you’d have to say yes.”

The media loves to portray fashion designers as solitary geniuses, intuitively spinning out ideas that somehow manage to capture the zeitgeist (and the attention of consumers): the press shots that accompanied Matthew M. Williams’ appointment at Givenchy are a prime example of how they tend to be presented. In reality, most young designers – especially those without an external sales agent – must contend with the conflicting demands of dozens of external voices: store buyers, editors, key customers, publicists and collaborators, all of whom have their own priorities for the brand. Without someone to filter and mediate that stream of advice, it can quickly overwhelm. “We were young, and eager to please, and interested in hearing from all these experts,” says Cotton. “When you have so many people speaking to you, you’re trying to take everything on board because you want them to keep liking the brand.”

Cotton is keen to stress that the vast majority of the commercial advice they were given was sound and well-intentioned. “We always, always, always listened to the buyers,” he says. But they also had to navigate some damaging experiences. “This certainly wasn’t true of all the retailers,” he says, “but there were one or two buyers who would come into the showroom and just tell you to do what they’d seen other brands doing successfully. They’d seen something that worked, and they wanted us to repeat it. And we knew they’d be going around telling every other designer to do the same thing. I think that’s had a massive impact on the homogenization of fashion. It kind of f*cked the market.”

What’s more, as they began to work with more heavyweight global retailers, the financial side of the business became increasingly unwieldy. Typically, independent designers should receive a deposit from the retailers who will stock their collections, which they use to finance the production of the garments. But many of the biggest retailers refuse to provide deposits to designers, knowing that their clout is such that the designers will have to agree to extraordinarily unfair terms of sale. Furthermore, many of the larger retailers refuse to pay anything at all for the collections until 60 days after they have been delivered, meaning a designer can go for two months without any funds coming in to repay their production costs. “The better the stores, the worse the payment terms,” says Mdumulla. “It creates this huge hole in your cash flow.”

It was this instability that eventually collapsed Agi & Sam. The running costs of producing the collections, without any stable commitment from retailers or the larger brands who had committed to collaborating with them, became impossible to sustain. After showing their last collection for Fall 2017, the two decided to fold the brand. “It definitely had to end. There was no fixing it,” says Cotton. “But it was so, so sad. It was like losing a relationship. And there are so many questions: could I have done this differently, was this a mistake?”

“We’d lost our perspective on the brand,” says Mdumulla. “When we’d started it was all about not taking fashion too seriously. But by the end we’d kind of lost our way. We didn’t know what Agi & Sam was. Or who we were, really.”

“It’s a hype machine. And that’s not something that you can build a sustainable business on.”

Shaun Samson had no real idea of starting a business when he completed his MA at Central Saint Martins in 2011. “I didn’t even have plans to properly produce my graduate collection,” he recalls. Nevertheless, at his graduate show, he was approached by a publicist from the Parisian PR firm Totem, and a representative from Dover Street Market, who wanted to buy the collection for their stores. It was, as Samson describes it, a dream opportunity. “These were the kinds of people I wouldn’t even have hoped to meet. I hadn’t considered that it would even be possible.” He was — needless to say — rather green at the time. “I remember the rep from Totem coming up to me after the show and saying, ‘We want to represent you.’ I was like, ‘I don’t even know what that means!’”

One opportunity led to another, and his eponymous brand was born the same year he graduated. “Suddenly I was in all the Dover Street Markets, all of the Opening Ceremony stores, Corso Como, Harvey Nichols Hong Kong. I was very aware of the luck that I’d had so quickly. I looked to my left and my right at my peers, and only a few of them seemed to be getting these kinds of successes.” (Samson graduated in the same class as the designers behind Marques’Almeida, and a year before London’s greatest success story of this generation, Craig Green).

Like Mdumulla and Cotton, Samson soon found himself at the helm of a rapidly ascending brand, in which he quickly – and publicly – had to learn the ropes. “I had a lot of help with the visuals,” he says, noting the stylist Matthew Josephs as a major support. “But I didn’t have anyone that could help with the business.”

To survive, he formed connections with his contemporaries within the industry, particularly the other designers showing alongside him during London Fashion Week. While sharing a showroom sponsored by the British Fashion Council in Paris, they’d exchange their experiences and try to learn from one another’s mistakes. “We all had each other, so you’d hear the horror stories,” he says. “Like, ‘Oh, watch out for Barneys, because they’ll put in a big order and then they won’t pay’ – even though they’d come to the showroom acting like the kings and queens of fashion week.” In spite of the camaraderie, he learned his commercial lessons the hard way. As Samson sees it, he was placed in the unenviable position of having to make negotiations with major international stores, despite having little understanding of what he should or shouldn’t accept.

A store typically buys the entirety of its stock outright from the designer at the start of the season. Those funds help to finance the collection, and any unsold products can be marked down by the retailer at the end of the season to clear them from the shelves. However, under a “sale or return” model – a policy which is generally considered among designers to be deeply unethical and exploitative – the store waits until the end of the season before paying for any garments it has sold. Everything unsold is shipped back to the designer — and not paid for, leaving the designer with mounds of unwanted stock and no means of selling it.

“I don’t want to be the face. I just want it to stand on its own.”

“I didn’t even know that ‘sale or return’ was a thing,” Samson says now. “So I certainly didn’t know that I needed to avoid it. The buyers just told me it’s what I had to do. And these were my dream stores to be in. I only realize now that they were only doing that to me because they didn’t make any money themselves.” Samson felt paralyzed: trapped in unfair sales contracts, yet unable to ask for fairer terms for fear of damaging his relationships. “They’d do these things that are so shady, you’d end up sitting on thousands of dollars of unsold stock and the next season they’d want to come back and order more. And you’d have to say yes.”

If Agi & Sam’s resources became a slowly dwindling stream, Samson’s finances were quickly becoming a sinkhole. Without the upfront payment that the retailers should have provided him, he was forced to front the costs of production entirely from his personal finances – and, soon, with money loaned to him by his parents. “On the one hand, it was going great,” he says. “Sales were growing, the stockist list looked good, I was getting a lot of press, and my Japanese distributor was happy. But it became this hamster wheel. And you can’t stop the wheel. You have to keep going and keep going.” And all the while, the pace was increasing. At the brand’s peak, Samson worked every day of the year except Christmas Eve, returning to his studio on Christmas Day. He remembers, too, working alone on the collection while the New Year’s Eve countdown played in the background on the television. “I just remember being glad that I hadn’t gone to see my friends,” he says, “because it meant I could keep on working.”

The wheels came off before long. As the orders got bigger and bigger, Samson needed more and more money to fund the production, despite having no guarantee that the stores would pay him back for the garments he created. “I had to go back to my parents to ask for more money,” he recalls. “And by that point they didn’t have any more. So they offered to put their house up for sale for me.” It was at that moment that Samson realized his business had become unsustainable. “I was not going to make my parents homeless to fulfill store orders,” he says.

Samson put the label on hold, planning to take a moment to regroup and figure out how to save his brand. “But as soon as I paused the label, I realized how much I hated it,” he says. “It sucked. I couldn’t think about my label anymore: it was putting me in a place where I just hated everything.” He gave up his studio, returned to his parents’ home in Los Angeles and just stopped looking at his emails. In the five years since, he hasn’t checked them once.

Patrik Ervell joined the industry the better part of a decade before Cotton, Mdumulla and Samson, at a time when a burgeoning brand could still find its footing. Though he made his “official” debut for Spring 2006, his label had slowly been percolating before it was put under such an intense spotlight. “I had a fairly gentle introduction to the industry,” he says. “I was just making some T-shirts for a friend’s shop, and that was the starting point for me becoming a designer.” The friends in question were Ervell’s classmates at UC Berkeley, Humberto Leon and Carol Lim – the founders of the Opening Ceremony boutiques.

Unlike the generation of designers that followed him, Ervell was given the space to grow and evolve the brand at his own pace, adding new categories or product ranges when it made sense to him rather than capitulating to the intense pressure for constant growth. “I was lucky to have Opening Ceremony, which at that time was a kind of incubator for me,” he says. “There aren’t many retailers that support designers in that way today. I don’t think that’s been possible for at least a decade – to be able to grow your brand at a natural progression.” But by focusing on honing his aesthetic, revisiting and tweaking styles instead of aggressively expanding, he was, in fact, able to create a more sustainable and manageable business model. “I outlived a lot of my peers,” he laughs.

Nevertheless, despite a less turbulent rise through the industry, his brand wasn’t immune to the challenges faced by others. “It got complicated,” Ervell says. “Soon there was Barneys, and the other major department stores, and international retailers at one time or another. And it meant that less and less of our time is devoted to designing the collections, which is the reason why I started the brand. Because you have to run a business. And that can be tricky.”

Ervell’s objective for his brand was simple: to make beautiful products that people will want to wear. He was, and is, resistant to the idea that designers should have to constantly move their brand onwards. “‘Newness’ is the word they’re always using in our industry. ‘We need newness.’ But I’m just not interested in churning out novelties for men,” he says. “And men aren’t interested in that either.” At the same time, he received pressure from some corners to make his collections more bombastic. “Being an emerging designer – a store isn’t buying them for simple clothes,” he says. “They have other companies that take care of the nice product that people want to wear. What they come to a young designer for is something else: it’s a hype machine. And that’s not exactly something that you can build a sustainable business on, in the long run.”

Ervell, ultimately, closed his own brand too. His last runway show took place for Spring/Summer 2018. But closure wasn’t a crash-and-burn: instead, he sidestepped into a new role at the Californian contemporary brand Vince, which he joined as Vice President of Men’s Design in late 2017. He found, quite quickly, that working within an established brand offered him a new focus. “I’m spending my time designing products that people want to buy and wear. Which is actually what I wanted to do at the beginning,” he says. “You don’t end up doing that when you have your own label. I feel much more fulfilled, and happier, as a gun-for-hire.”

He believes, too, that his timing was fortuitous: as the long-tail effects of the pandemic cause ever-increasing economic chaos, the prospect of professional stability in a financially robust business is an appealing one. “I was happy to have exited the party when I did,” he says. “And I’m especially happy about it now. This is where I want to be working today, especially in this current climate I feel perfectly positioned for the next 10 years of menswear.”

Mdumulla, Cotton and Samson, thankfully, landed on their feet. After a stint working with a British luxury label, Mdumulla has begun consulting for a number of brands alongside starting a family. Though he has no immediate plans to open a new line, it’s not something he would rule out. “I’ve had time to really think,” he says. “There’s so many things I wish I’d known the first time. But I knew, even then, that the system was flawed. So I was really happy to sit for a bit, and take my time, and decide what I want to say next.”

Cotton, too, has launched a design and material innovation consultancy – and a new brand. “I’d thought I’d never want to run a brand again, ever,” he says. “F*ck that. But I met with a company that has its own factories, its own production manufacturers, its own space. So I asked if they had ever thought about starting their own line.” The result is Raiment, a contemporary label that focuses on tweaked versions of classic British designs – exactly what Cotton wanted to create from the outset of his career in fashion. And, working for a label that no longer has his name on it, he’s found comfort in the relative anonymity. “I don’t want to be the face,” he says. “I just want it to stand on its own.”

As for Samson, he’s stayed in Los Angeles since the aftermath of his brand’s closure, where he’s found work within an Italian luxury label’s U.S. studio. Like Ervell, he has come to love the stability and focus that comes with working within an existing brand – but, he confesses, there are moments when he misses the old days. “When I had my own label there was a lot of validation for me, and for my work,” he says. “And of course, that’s not the same when you’re working for another company. Ultimately, it’s not really my work: it’s in service of a creative director’s vision. I think I need to get over it. It’s probably not my place to seek validation for my work anymore.”

Would he ever revive Shaun Samson, the label? “I don’t think it would be under my own name. I don’t want to be a brand. And there’s loose ends that I don’t want to have to face. But, who knows? In the end, it was so sh*tty. But I’d be lying if I said it didn’t have its moments. If I were to start it again though, there’s one thing I do know: I wouldn’t put my own money into it.”