In an eco-anxious world, it has become difficult to tell whether brands are truly invested in ecological change or employing subtle marketing spins. As consumers become increasingly aware of environmental issues, brands have taken to eco-friendly narratives as convenient shortcuts to higher profits. It’s much easier, after all, to lay claim to sustainability than to practice it. If there’s one label challenging this dissonance, it’s BOTTER. Founded by Rushemy Botter and Lisi Herrebrugh in 2017, early collections called attention to the pollution growing around their Caribbean homes of Curaçao and the Dominican Republic. “As a child, I very clearly remember the beach,” says Lisi. “I could see my father snorkeling through the water and seeing the beautiful coral reef. Now, you can’t even take a swim without catching something between your fingers or stepping on glass.” The two believe there should be substance tied to sustainability. “For us, it’s not about screaming that you’re doing it,” Rushemy explains. “It’s about doing it in silence.”

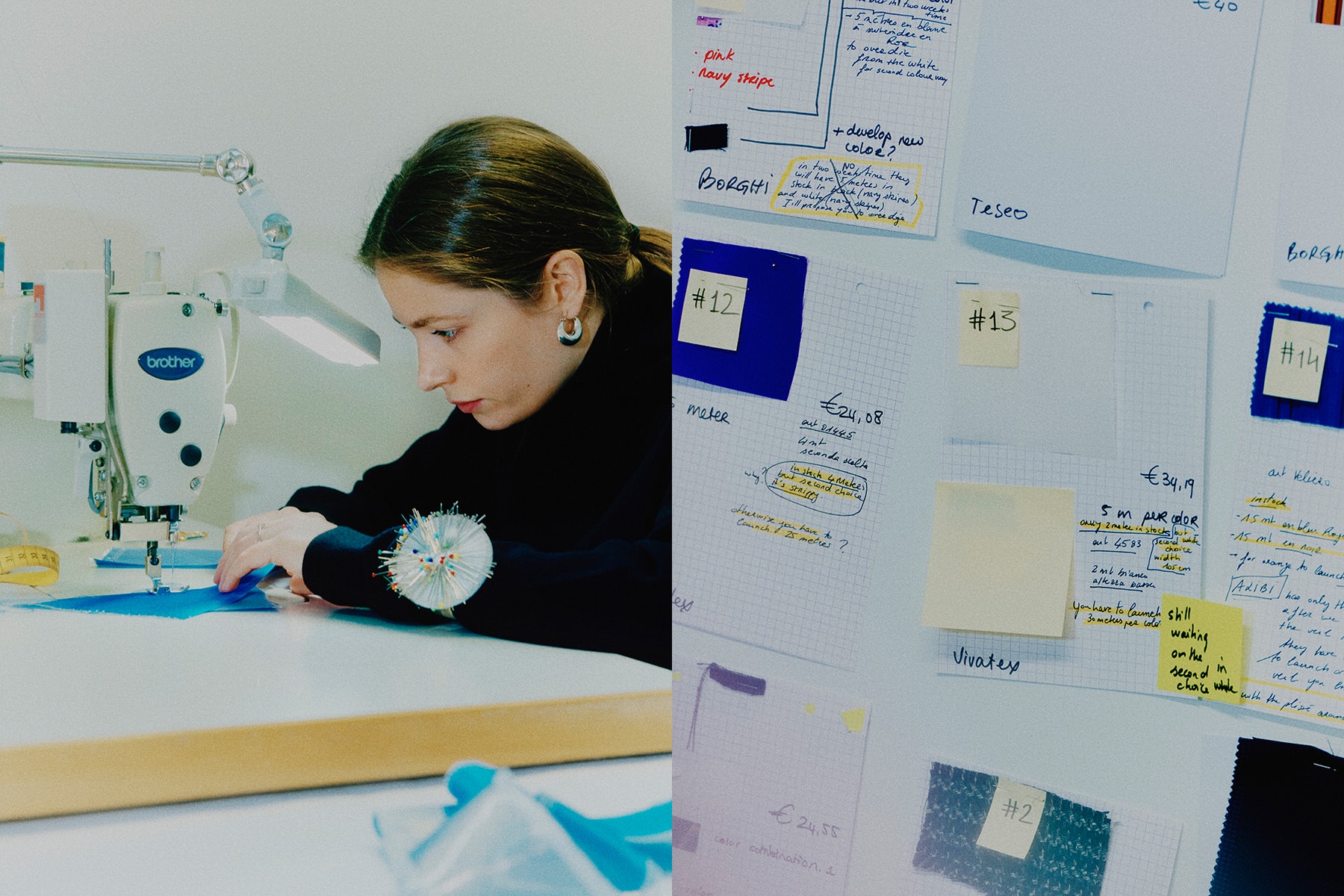

Spread between the design-conscious city of Amsterdam and the breezy sun-stained coasts of the Caribbean, Herrebrugh’s and Rushemy’s cross-cultural roots are reflected in vibrant colors, exaggerated volumes, and eco-friendly textiles. The duo first started working together at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, a school whose alumni include Raf Simons, Martin Margiela, and Dries Van Noten, to name a few. “In Antwerp, they push you to dream big, to create fairytales, and to be conceptual. It’s all created by hand, and it’s all manual.” In just a few years, the two have managed to win the 2018 Festival d’Hyère’s Grand Prize, were finalists for the 2018 LVMH Prize, and were appointed creative directors of Nina Ricci in the summer of 2018.

We sat down with the duo ahead of their Fall/Winter 2020–21 show to discuss their work, their appreciation for individuality, and what they believe to be the most urgent sociopolitical issues.

When did you guys realize you wanted to collaborate together to start BOTTER? How has the vision for the brand changed since day one?

L: I think our vision grew very early. We had this big dream about starting something together. It was an organic thing. We talked about a lot of things, and we really felt like it was the right time to start it. We had nothing to lose.

R: We also felt we were doing something quite personal and unique. I was in my second year at the Academy in Antwerp when Lisi came to live with me, presenting our collections and working in Antwerp—it’s a tough school.

L: It’s a bubble, but we were already participating in competitions in our second year.

R: We didn’t just work on school projects. We saw school as an opportunity to work with other people and connect. In Antwerp, you have sculptors, painters … the artist community is really big. You’re connecting with other worlds and building relationships.

Living in Europe and studying in Antwerp, what does that shift of coming and going to your respective homes look like?

L: Rushemy was born in Curaçao, and I was born in Holland, but the bond with my family in the Dominican Republic is very strong. It’s very different in the Caribbean compared to Europe. You have to take care of your parents, your parents have to take care of their parents, and we all live in the same house.

R: We were raised in both the Caribbean side and the Dutch side, but we have friends and family on both, so the shift isn’t that big for us. I think you can see that in our collections—the structured, sober side as well as the more colorful and playful side.

“People see whether you’re being genuine or trying to be someone you’re not, and they’re more curious when you’re being genuine.”

So what does your brainstorming process look like?

R: We’re constantly looking around. We collect things, make pictures, print them out, put them in a book. Everything we find interesting, we put in. It’s how we were trained.

L: We archive things. It’s not structured or anything, but it’s just a big book piling up or a big file on our phones. We’ve done a lot of files and sketches. Archiving is like settling ideas.

What does it mean to be progressive or avant-garde in fashion today?

L: We don’t believe you need to be shocking to be noticed. There are a lot of brands that focus more on creating beautiful seams and developing solutions. You just need to stick to your own universe. I really believe there is a customer for everybody.

R: It’s about being true to yourself and not being insecure about showing who you really are. When we create, we have fun. People see whether you’re being genuine or trying to be someone you’re not, and they’re more curious when you’re being genuine.

In some ways, being environmentally friendly is becoming a “trend.” What are your thoughts on this?

L: I think we got a little afraid of the word “sustainability” because it’s true, it’s kind of a marketing tool. For us, we started this out of honesty and out of real worry.

R: For us, it isn’t about screaming out we’re doing it. It’s more about doing it in silence, and if it shows, that’s a plus.

L: Everything we do has a personal touch and requires a lot of research. It’s easy to find random sustainable fabrics, but finding a particular fabric, making sure it integrates well with the collection and seeing what a supplier’s doing for the environment takes more time. It’s very important for us to create lasting designs, and I think it’s a sustainable way of thinking.

“I think we got a little afraid of the word “sustainability” because it’s true, it’s kind of a marketing tool. For us, we started this out of honesty and out of real worry.”

The SS18 “Fish or Fight” runway incorporated inflatable toys. This seems like a recurring theme in your shows. What do you want to convey with this?

R: We are very conceptual designers. Sometimes we want our shows to be digestible, but for us it’s much deeper. There are multiple meanings for the blowup dolphins. For example, you can think of plastics in the ocean affecting dolphins. You can also see it from the perspective of local Caribbean residents selling toys to tourists—they work all day in the burning sun so they can feed their families. We want to keep the conversation open and not push the ideas in your face. We want people to start asking questions.

THIS STORY WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN HYPEBEAST MAGAZINE ISSUE 28: THE IGNITION ISSUE AS “SHIFTING CURRENTS”. FIND OUT MORE HERE.

Photographer

Julien Lienard