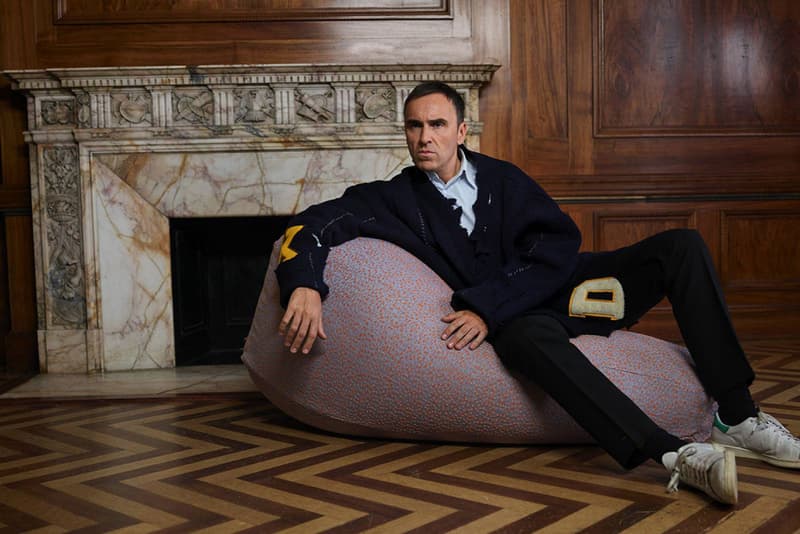

Raf Simons Reveals More Reasons Behind Why He Left Dior

“The reason why I came to Calvin is because it has the highest and the lowest and everything in between, so you can reach out to everybody.”

In a recent interview, Raf Simons spoke at a greater length on why he left Dior. After spending three years at the highly-esteemed fashion house, the Belgian designer decided to part ways before surprisingly joining Calvin Klein. In the interview, the popular designer talked about how he used to be enamored with Helmut Lang, but unable to afford any of his pieces. “Of course you want some connection for yourself, but some brands it’s just not possible. You could not even buy a lace of a sneaker, it’s just too expensive,” noted Simons. He then goes on to say that, “To be really honest, the attraction and the reason why I came to Calvin is because it has the highest and the lowest and everything in between, so you can reach out to everybody. Which, in high fashion, is not always easy. It was not something that was possible at Dior, for example. It is possible at Calvin Klein.”

Check out an excerpt of the interview below, and read the full piece at Amuse.

In another interview, Simons talks about Rick Owens and how fashion isn’t built to last.

What materials do you dislike working with?

I’m always scared of somebody asking me, “What do you not like?” because everything is an evolution, so it might come back to me if I feel it’s right. But, for example, when things go more plasticky. And yet in that time — you could almost call it plastic time — during the 60s and the 70s, designers made very strong suggestions for living environments. Joe Colombo with Visiona, this whole kind of world where there was a lot of experimenting with plastic.

It’s just a personal thing that I don’t like to sit on something that has plastic, but I think the suggestion was interesting because it was more connected to environment. It was more placed in the idea of how we live our lives. In the 60s, we were dreaming about the future and the space age, the possibility of travelling to the moon, inventions. And out of that came all that kind of space age furniture. First, romantic, and afterwards quite liberated.

More and more, I think that the design world becomes very object-oriented — always about designing a piece, an object. It’s not a critique, but what I kind of miss a little bit is the suggestions from people actually responsible for all these designs to place it more in the reality of our lives — what it is about, or what it could possibly be about. Because it can be anything. It can be reality, it can be a future dream. Now, I think, it’s done by decorators. And I just keep wondering how one person — a designer, a furniture designer — could push it further. Visiona and Joe Colombo is for me the biggest example. I just think it was incredible how he kind of imagined, for himself and the people he was designing for, new living. New ways of living, new possibilities.

John Waters talks about his artworks — Mike Kellys, Cy Twomblys — as his roommates and about what it’s really like to live with pieces art.

It’s very inspiring to me to connect to the thought processes of other people. And it’s not always about that specific work. If I have Sterling around me, it’s because I’m really interested in his thinking and it feels good to have that around me. The same for other artists’ work I live with. Sometimes I know them and sometimes I don’t. Sometimes they are my generation and sometimes not. I haven’t read the John Waters book, but it’s like you say: interesting because they’re all different kind of characters in a way.

Sometimes I’m scared to talk about it because people can also think you’re pretentious when you always connect to art and you’re not in the art world. But I cannot explain it. It’s something I am connected to since I was 16. It’s like breathing air, or drinking Coke Zero. It’s a daily thing, an automatism. If I have a moment, I’m looking at art sites to inform myself about shows and reviews because I have less and less possibility to go around. Of course, going around is the best experience.

Does it bother you that someone may be so influenced by your work but never have the chance to touch it?

Well, with Calvin underwear now that could be possible! To be really honest, the attraction and the reason why I came to Calvin is because it has the highest and the lowest and everything in between, so you can reach out to everybody. Which, in high fashion, is not always easy. It was not something that was possible at Dior, for example. It is possible at Calvin Klein.

I remember when I was a young kid — not 16, more like 19 or 20 — I was obsessed with Helmut Lang. I couldn’t afford it, but I was connected. That was my world. Fashion-wise, it was my world. And at one point, I could maybe buy a shirt, but I was completely a Helmut Lang kid. It’s more about how you connect to it in your mind, I think. Of course you want some connection for yourself, but some brands it’s just not possible. You could not even buy a lace of a sneaker, it’s just too expensive.

I spoke with Willy [Vanderperre] before his recent show at Red Hook Labs, and there was a similar motivation. He made stickers and pins and patches in limited editions so that they were still art objects, but accessible to young people.[Willy and I] are very close, so it’s always one way or another about having a connection to youth. Like the Sacco, the ultimate teenage element. Back in the days when I was studying industrial design, I wanted a Sacco so badly but I could not afford it. So I would just copy the pattern and make one. It’s nice, you know, this kind of do it yourself. I am the same with my brand. If I can be inspiring for kids, I’m already super happy. If that means that if I do a black coat and they find one in a vintage store and they tape it up, I love it! That’s interesting to me.