Top 10 National Pavilions to Check out During the 2024 Venice Biennale

The world’s biggest art exhibition is back for its 60th edition, dubbed “Foreigners Everywhere.”

“Stranieri Ovunque” or “Foreigners Everywhere”, became both the slogan and a call for action for this year’s Venice Biennale, which heralded its first South American curator, Adriano Pedrosa. Founded in 1895 and going on its 60th edition, the biggest art exhibition in the world broke a number of social barriers this year as an array of indigenous artists took center stage representing a number of major pavilions, from Jeffrey Gibson (USA) and Sir John Akomfrah (Great Britain) to Glicéria Tupinambá (Brazil) and Archie Moore (Australia).

The latter artist delved into his family tree to retrace over 64,000 years of Aboriginal histories, emphasizing the discrimination that indigenous communities continue to face in Australia. “It’s quite political, but it’s also quite poetic,” Pedrosa tells The Art Newspaper, describing the title of this year’s Biennale. Venice as a city is a fitting location for the Biennale’s theme. A city that was once a safe haven for Roman refugees, which was later colonized by both the Austrians and Napoleon Bonaparte, as well as having once served as the largest biggest center of trade in the Mediterranean.

Today, Venice is home to roughly 55,000 people, but doubles in capacity when tourists flock to its quaint canals in the high season. There are foreigners everywhere, but as Pedrosa asserts, “wherever you go, you are always, deep down, a foreigner yourself in a more subjective manner—in a psychological, psychoanalytic way of thinking of “the foreign”. It also evokes Freud’s Unheimlich, the famous text that he wrote on the uncanny, where what is strange is also quite familiar.”

Spread across the city, from national pavilions to auxiliary events, the 60th edition of the Venice Biennale is officially underway and Hypeart was on the ground touring some of the best shows to check out while its on view until November 24. Check out our top 10 pavilions below and read more about scheduled programming here.

Australia

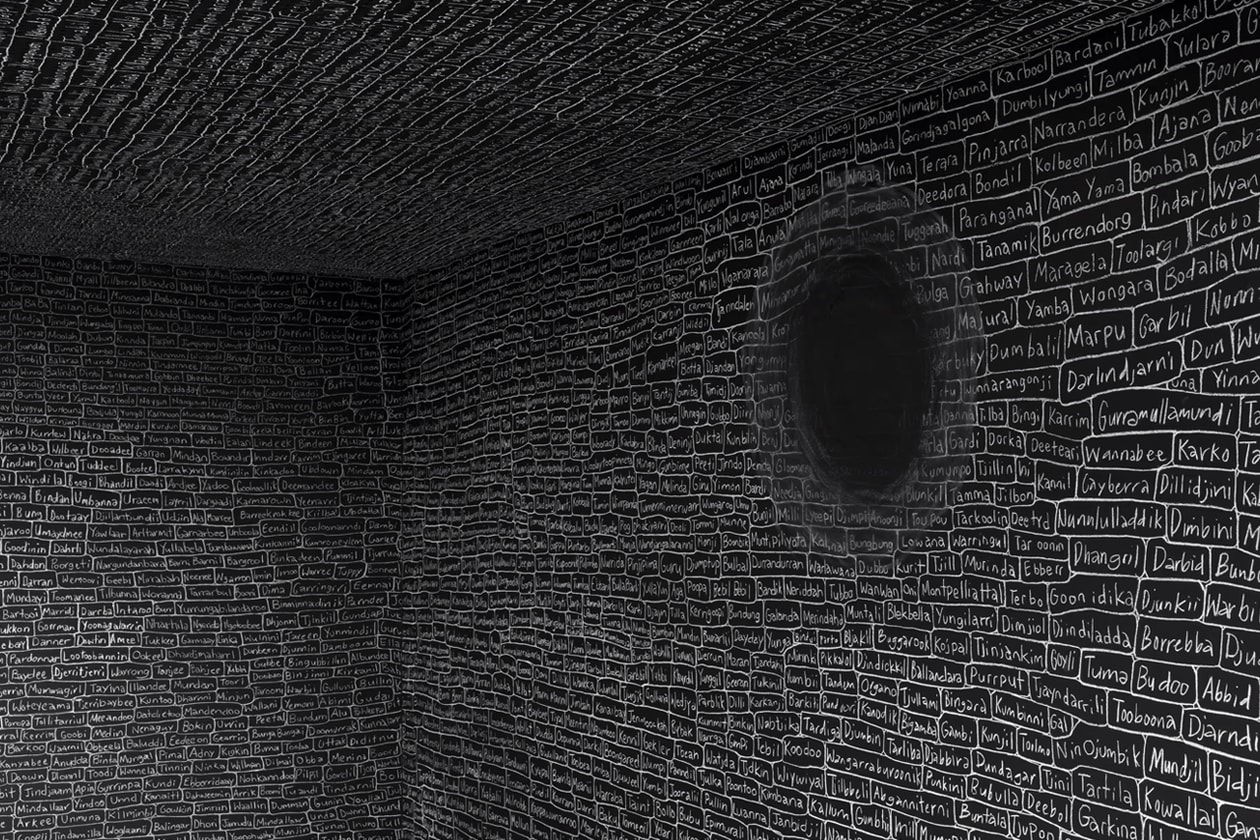

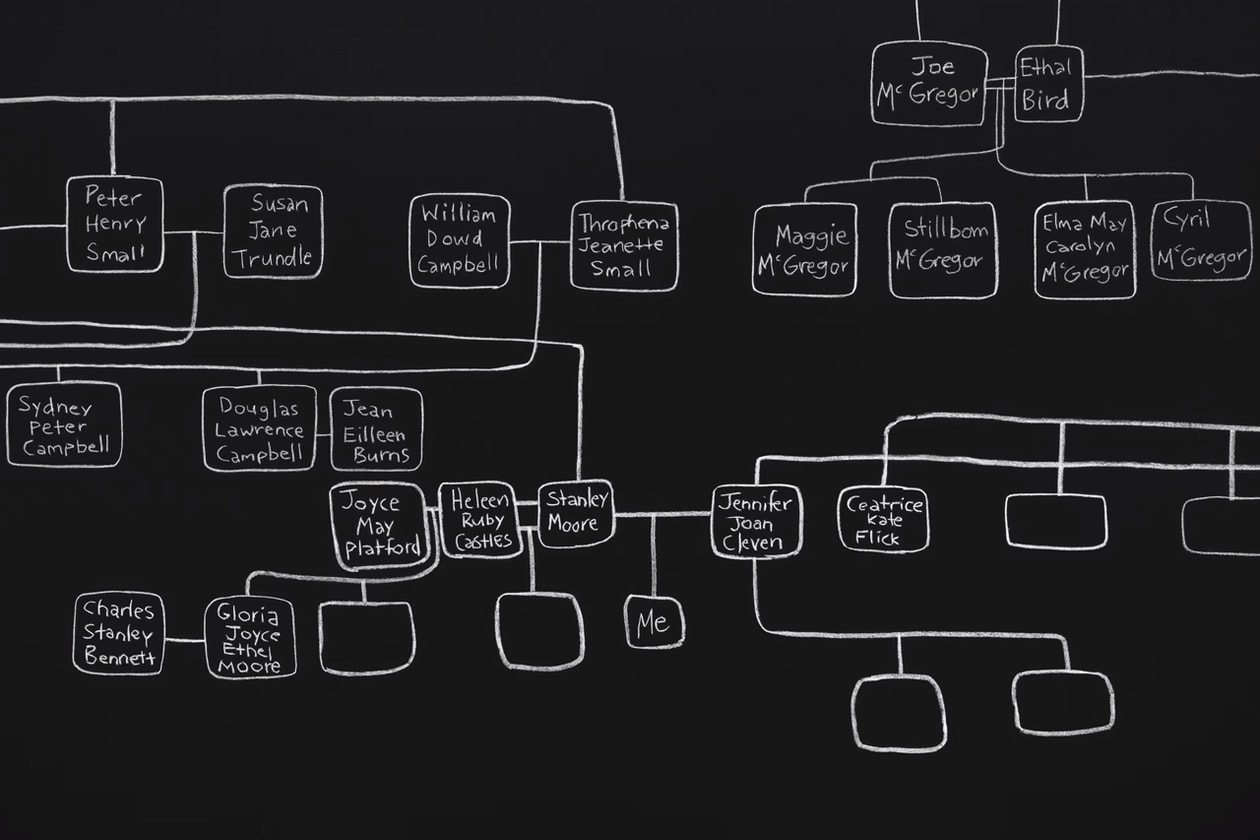

To kick off the list, we start with the Australian pavilion, winners of the Biennale’s Golden Lion award for 2024. While massive LED lights and towering displays adorned the spaces of many national pavilions, the nation down under reverted back to one of art’s first modes of expression — chalk. Over the last two months, Archie Moore, who is of Bigambul-Kamilaroi heritage, has been drawing the names of thousands of deceased Aboriginal peoples in fragile chalk on blackboard as a commentary on the inconsistent transmission of knowledge and the consequences these gaps in information have herald on future generations.

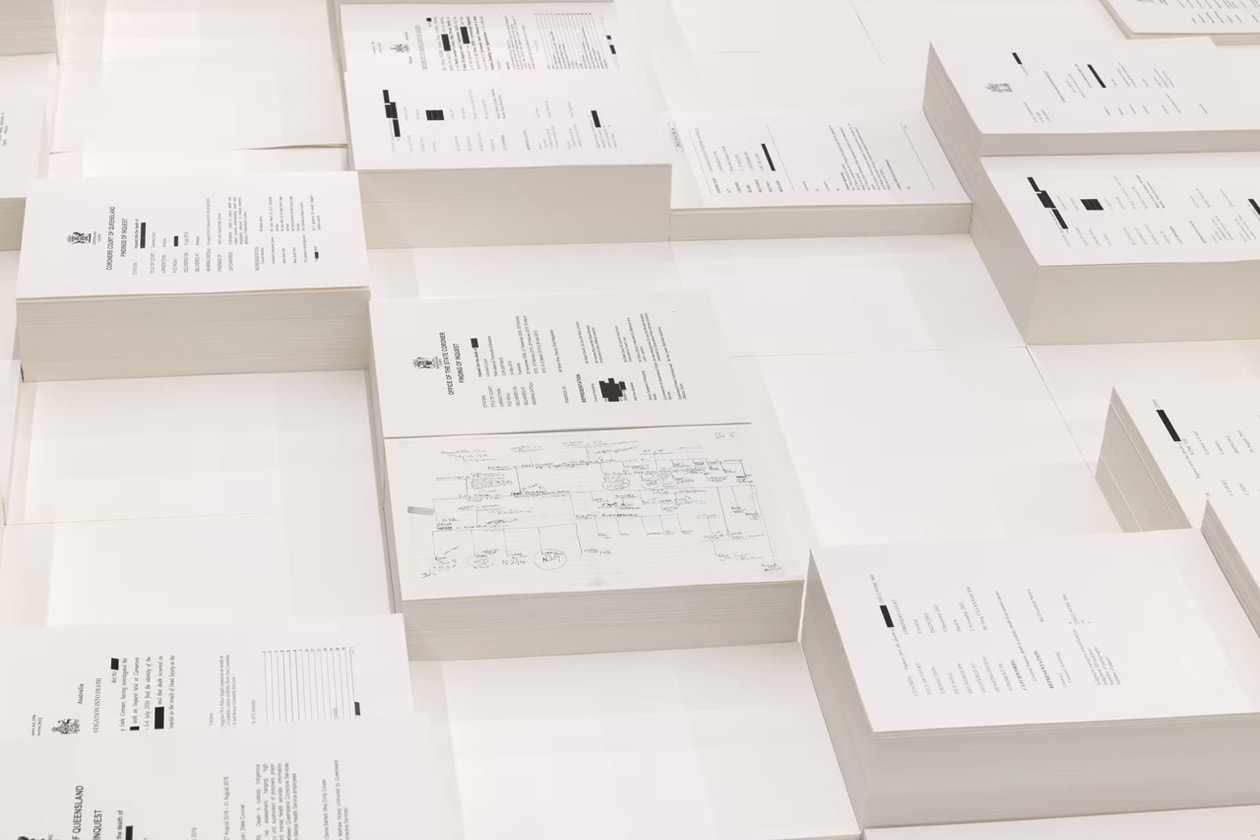

Curated by Ellie Buttrose, kith and kin starts with Moore’s own family tree, quickly extending up and across the walls of the space to cover over 65,000 years of Aboriginal histories, one of the oldest groups of people in the world. Designed by architect Kevin O’Brien, who is of the Meriam and Kaurareg peoples of the Torres Strait, two luminescent white boxes hover over a white table in the center, which holds records of 557 Aboriginal people who have died by police brutality since 1991, with gaps purposefully left between stacks to note the lapses in our understanding thus far. Surrounding the table is a pool of water that acts as a reflection on violence, abuse and Australia’s colonial history. “You have to lean across the water to glimpse them,” Buttrose tells the Guardian, “and you see your own reflection as you do. You become part of the work; you have to look at yourself in the context of all this loss.”

Scribbled on the walls are the names of Aboriginals who had to take on the names given to them by their colonizers, or circles left blank as a result of erasure or gaps in recorded information. The title of the show, kith and kin refers to friends and family today, but it’s earliest definition in 1300’s Old English denotes a native land or countrymen. “I’m just trying to give an impression of this huge amount of time and Aboriginal inhabitation on the continent,” Moore said. “And I’m including everyone in the tree. If we go back 3,000 years, humanity all has a common ancestor. So it’s about the human global family tree as well.”

Brazil

The Hãhãwpuá pavilion, as Brazil’s showcase has been renamed this year, is the first time its exhibition has actually described the struggles of Brazil’s indigenous communities by indigenous artists themselves. Glicéria and Olinda Tupinambá, who hail from the Tupinambá community of Serra do Padeiro in Northeastern Brazil, worked alongside artist Ziel Karopotó to present Ka’a Pûera: we are walking birds.

The exhibition’s title refers to harvested terrains that look infertile, but reemerge to give way to a crop of sacred and medicinal plants. Concurrently, the name alludes to a small bird that walks Brazil’s jungles, camouflaging itself to the environment, as well as the popular fighting style that was first disguised as a dance, but was actually intended as a form of self-defence by enslaved Africans and indigenous populations in the 18th century.

On view are a series of drawings, paintings, multi-media sculptures, films and installations that tell the continual resistance of indigenous people in Brazil, along with exploring themes related to human rights and the climate emergency. “The exhibition is being held in the year in which one of the Tupinambá mantles returns to Brazil after a long period in European exile, where it had been since 1699 as a political prisoner,” said curators Arissano Pataxó, Denilson Baniwa and Gustavo Caboco. “The garment spans time and brings the issues of colonization into the present day, while the Tupinambá and other peoples continue their anti-colonial struggles in their territories – like the Ka’a Pûera, birds that walk over resurgent forests.”

Czech Republic

Repatriation pervades many of the exhibitions across the Biennale, but for the Czech Republic, an emphasis on society’s violent and hierarchal relationship to the animal kingdom is of equal importance. Curated by Hana Janečková, The heart of a giraffe in captivity is twelve kilos lighter tells the story of Lenka the giraffe, the large hoofed mammal who was captured in Kenya in 1954 and shipped to Prague, where it became the first Czechoslovak giraffe. Lenka only lived for two more years, as it died and its body was donated to the National Museum of Prague whose taxidermy workshops cleared it out and displayed it until 2000.

Artists Eva Kot’átková, Himali Sign Soin and David Tappeser recreated the Czech pavilion to retell Lenka’s story as a poetic series of installations, 3D sculptural iterations of the giraffe’s bones and a captivating live performance that recreates the animal’s life and death. Most immediately visible when entering the space are two massive tunnels that mimic Lenka’s spindly neck. Aesthetically, the installation appears like the decor that one would find in a toddler’s playpen. Instead of plush animals, however, the severed limbs of Lenka’s neck, torso, head and inners surround the expanse of the room as audience members gather around a small hole in the center of the pavilion.

“What is the difference between Lenka, the animal displayed in teh zoo and Lenka, the museum object with glass eyes?” asks Janečková. “Interpreted by children, educators and older people who were Lenka’s contemporaries, the installation is conceived of as a collective body facilitating multiple forms of storytelling.”

France

Entering the French pavilion is akin to being washed away in the complex entanglement of French-Caribbean relations. Commissioned by the Institut Français and supported by the Chanel Culture Fund, artist Julien Creuzet was selected as the first Black figure to lead France’s pavilion and chose the opportunity to explore themes related to emancipation and the struggles the Caribbean diaspora continue to experience with European modernity. Creuzet, who is also a poet, dubbed his exhibition Attila cataract your source at the feet of the green peaks will end up in the great sea blue abyss we drowned in the tidal tears of the poem.

Based in Paris, Creuzet cites Martinique (where he was raised) as the “heart” of his imagination. He starts his exhibition by reinterpreting the French capital’s famous Jardin du Luxembourg through a large film display depicting a sea of abstracted figures that hover against the Roman Tuscan columns that adorn the exterior of the pavilion. Like tiny statues of remembrance floating in an abstracted sea of broken chains and looted treasures, Creuzet reflects on France’s history of slavery within Martinique — the island where more African slaves were forced to produce sugar, worth more than gold at that time, than all of the U.S., except for Louisiana.

Creuzet works in fragments, creating multi-sensorial experiences made of spiritual sculptures, ethereal and sometimes bass-heavy soundscapes that are matched by floating tarantula-like installations consisting of colorful beads and chains made to appear like coral reef. Together, “it describes an immersion in a poetry of forms and sounds, volumes and lines in movement, colorful encounters forming new language: an experience to be lived deeply,” wrote curators Céline Kopp and Cindy Sissokho.

Germany

There was no pavilion that garnered a bigger queue on opening week than Germany. Curated by Turkish-German architect Çağla Ilk, who has won the Biennale’s Golden Lion award six times in the past, Thresholds consisted of three acts created in collaboration by Israeli artist Yael Bartana, German director Ersan Mondtag, artists Michael Akstaller and Nicole L”Huillier, alongside composer Robert Lippok and musician Jan St. Werner, who together, created a poignant reflection on representation, remembrance and the precarious future of the human race.

The side of the German pavilion’s exterior was covered almost to the ceiling in soil. The dirt is symbolic, as it comes from Anatolia, Turkey, where Mondtag’s grandfather immigrated from in the 1960s to help rebuild Germany following the post-war years. “I wanted to build a monument to working men that nobody knows [about],” Mondtag said in a previous interview, describing the forgotten history of immigrants, such as the director’s grandfather who enlisted in an asbestos factory and died due to cancer related to his work. Anatolian soil is further used across the floor, walls and inner structure of the German pavilion, creating a foggy and unnerving effect on the lungs as you traverse the space.

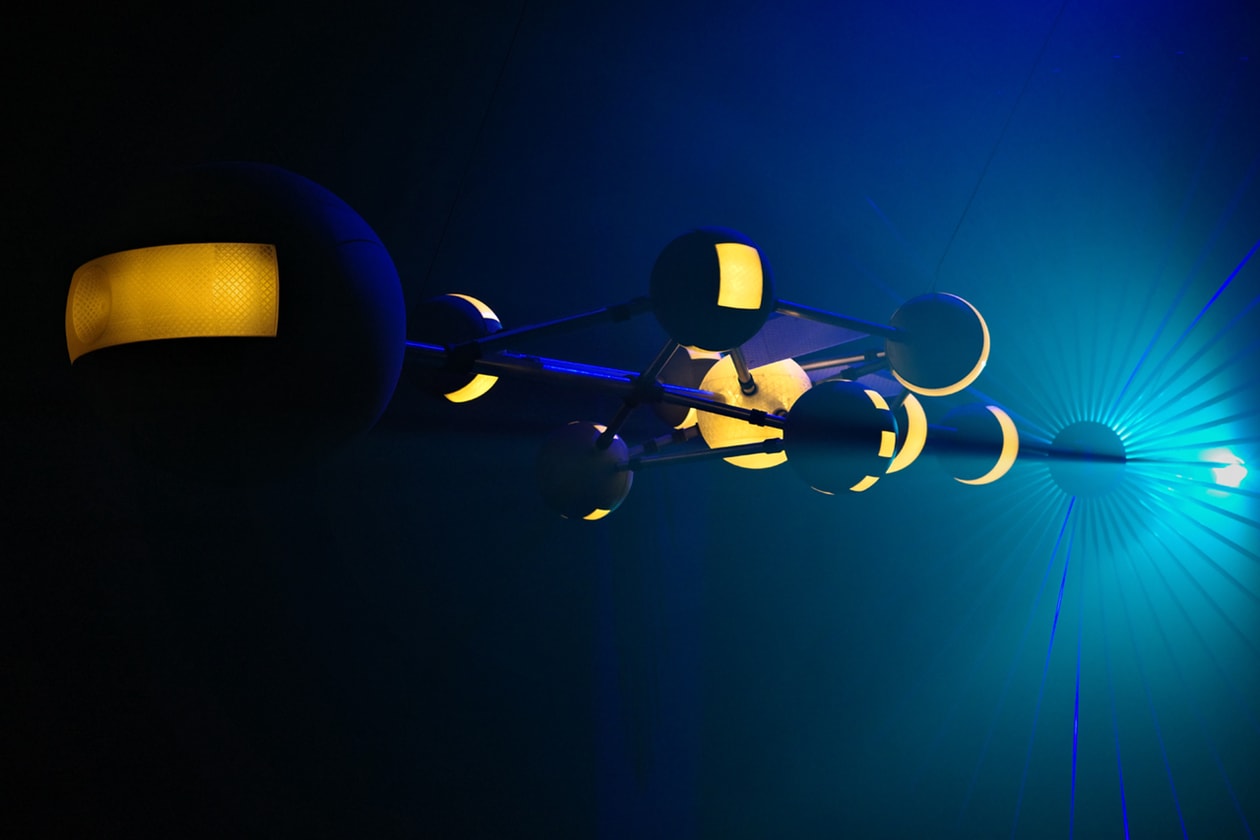

Audiences are immediately confronted by a large sculptural spaceship in the left room of the entrance, that is similar to the vessel in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). In the center lies a large curvilinear LED display showing the aforementioned spaceship as it jettisons across the cosmos, which cuts to scenes of modern-looking humans in mythological garbs performing rituals that our ancient ancestors would have done. Sonically, it feels as if being in a beating drum, a reckoning towards an uncertain future far away from the only planet humanity has known. The dirt-covered structure at the heart of the pavilion was actually made to mimic a worker’s apartment, as four live performers reenacted melancholic fragments of their life.

The migration story of Mondtag’s grandfather is “symbolic of the untold stories of millions of others who shaped the post-war era,” wrote Ilk. “In this respect, Mondtag opens up a space for the historiography of underrepresented groups that contrinue to receive little attention in a global discourse.”

Great Britain

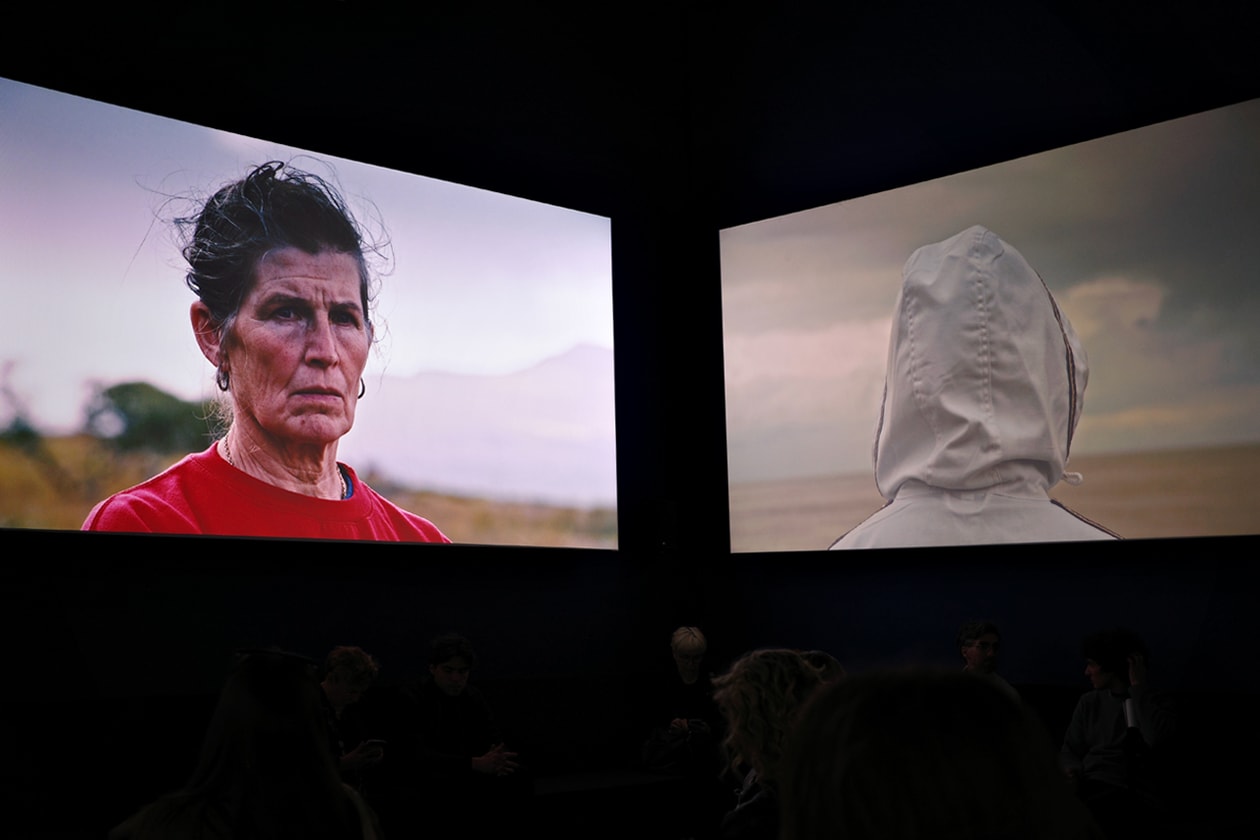

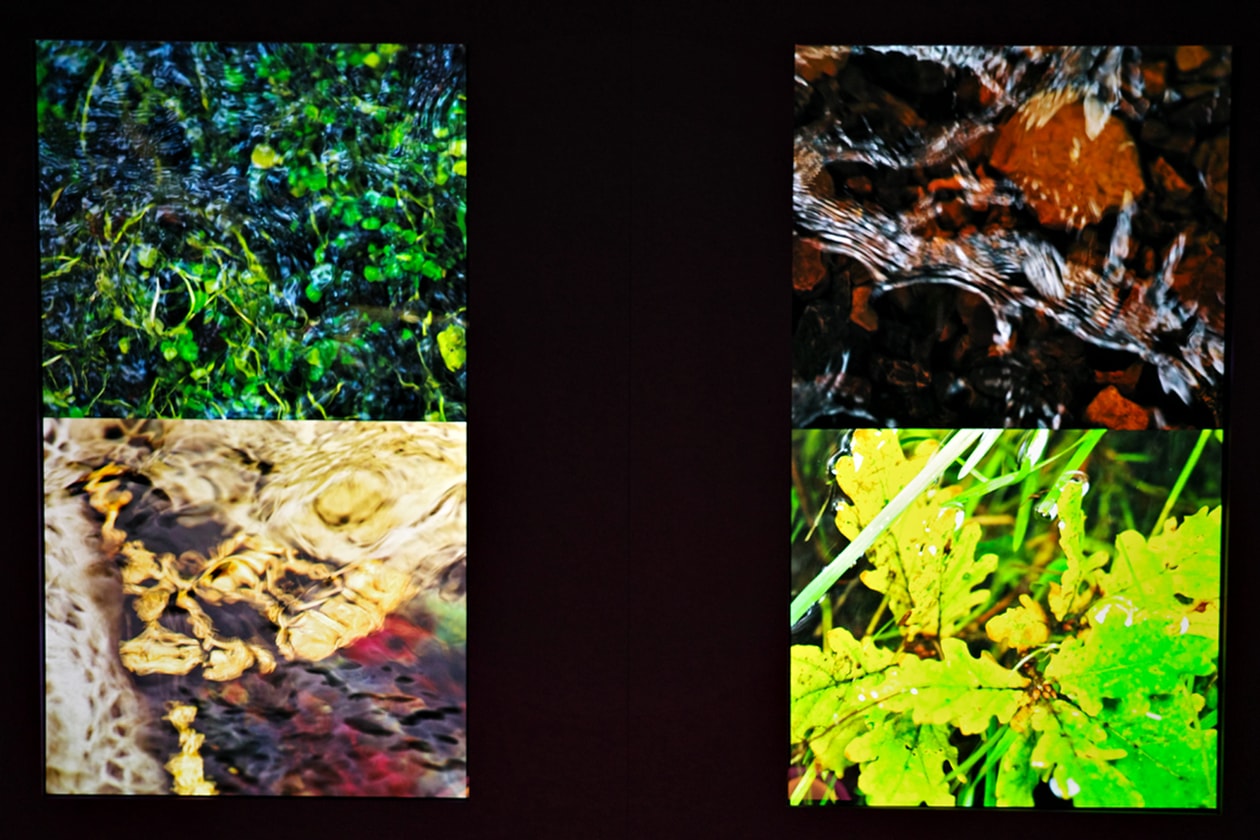

Ghanaian-born, British-raised artist Sir John Akomfrah creates moving films that probe into memory, racial injustice, migrant diaspora communities and climate change. As one of the pioneers of the Black Audio Film Collective, which aimed to bring Black cultural presence in the British media back in 1982, Akomfrah transformed Great Britain’s pavilion into a sensorial reflection that subverts post-colonial narratives.

Entitled Listening All Night to the Rain, visitors enter the building from the bottom level of the space, giving way to a series of multi-paneled monitors — each juxtaposing images of Holbein drawings from the Tudor period, as they wither away in a stream of water and ultimately ends with the death of David Oluwale, a British-Nigerian man who was drowned by two police officers in Leeds in 1969, which was largely forgotten until records surfaced 30 years later.

While known for his striking visual displays, listening is at the heart of Akomfrah’s exhibition. Each of the eight rooms are split into cantos, that together, work like a “collage,” the artist said, “everything jammed together or connected in some way, each one a sort of rummage into a specific economic or political past.” The sound of various bodies of water guide visitors throughout the building, from puddles and streams, rain to floods, as smaller LED screens give way to wall-to-wall projections. Akomfrah connects differing social issues from around the world, from police brutality in the north of England, the effects of climate change in South America to cries for emancipation in West Africa, through the universal reflection of water and the experiences of migrants in Britain.

“The exhibition is seen as a manifesto that encourages the idea of listening as activism and positions various progressive theories of acoustemology,” said curator Tarini Malik, “how new ways of becoming are roote din different forms of listening.”

Japan

Efficiency and cleanliness are pillars of Japanese society. But when slight messes occur, such as the small water leaks in the Tokyo subway, staff revert to everyday found materials to solve the issue. For Japanese artist Yuko Mohri, these makeshift solutions often resulted in quirky sculptural displays that in part inspired her pavilion, entitled Compose. Sook-Kyung Lee, who is both the curator of the pavilion and the Senior Curator of International Art at the Tate Modern, notes that Mohri’s makeshift water leak installations parallel a world in which floods are constantly threatening built and natural ecosystems, such as the city of Venice, who experienced its latest flood in 2019.

The Japanese pavilion, however, appears more like a laboratory or food processing plant than an exhibition, as Mohri connected electrodes into decomposing fruit, rendering their moisture into electric signals that flicker light throughout the space. As the fruit wither away, a smell of decay fills the air — a cycle that Mohri purposefully makes reference to the Buddhist “Nine Stages of Decay” — or the way in which life delineates a circle.

Chance is at the core of the pavilion, visually and sonically. “The exhibition asks what it means for people to be and work together in a world facing multiple global crises,” Lee said, adding that “The water leaks are never fully fixed, and the fruits end up in the compost to rot in Mohri’s installations, but these apparently futile endeavors indicate the glimpses of the solutions our humble creativity might bring about.”

South Korea

If sound dictated Akomfrah’s British pavilion, then smell was the defining sense emphasized for Koo Jeong A of South Korea. Neuroscientists state that scent is the strongest sense tied to memory, as odors directly enter the limbic system, the same part of the brain as the amygdala and hippocampus, which process emotions and memory. A of weightlessness is instantly present throughout the pavilion, which is left bare, barring infinity symbols embedded into the light oak wood, two wooden-shaped möbius sculptures and a scent-diffusing sculpture that periodically releases a different fragrance roughly every 10 minutes.

Entitled Odorama Cities, the site specific installation began back in the summer of 2023, when Koo asked via social media, one-on-one meetings and press releases for people to submit a scent that that reminds them of their memory of the Korean peninsula. “What is you scent memory of Korea?” wrote the invitation, which was accessible to both Koreans and non-Koreans alike. Over 600 entries entered with specific keywords that Koo and the Arts Council Korea then transferred to 16 expert perfumers in Paris, Shanghai and Singapore, resulting in 16 distinct scents that act as the artworks within the pavilion.

“With the new commission Odarama Cities,” the curators of the show explain, “Koo delves into the nuances of our spatial encounters, investigating how we perceive and recollect spaces, with a particular emphasis on how scents, smells, and odors contribute to these memories.”

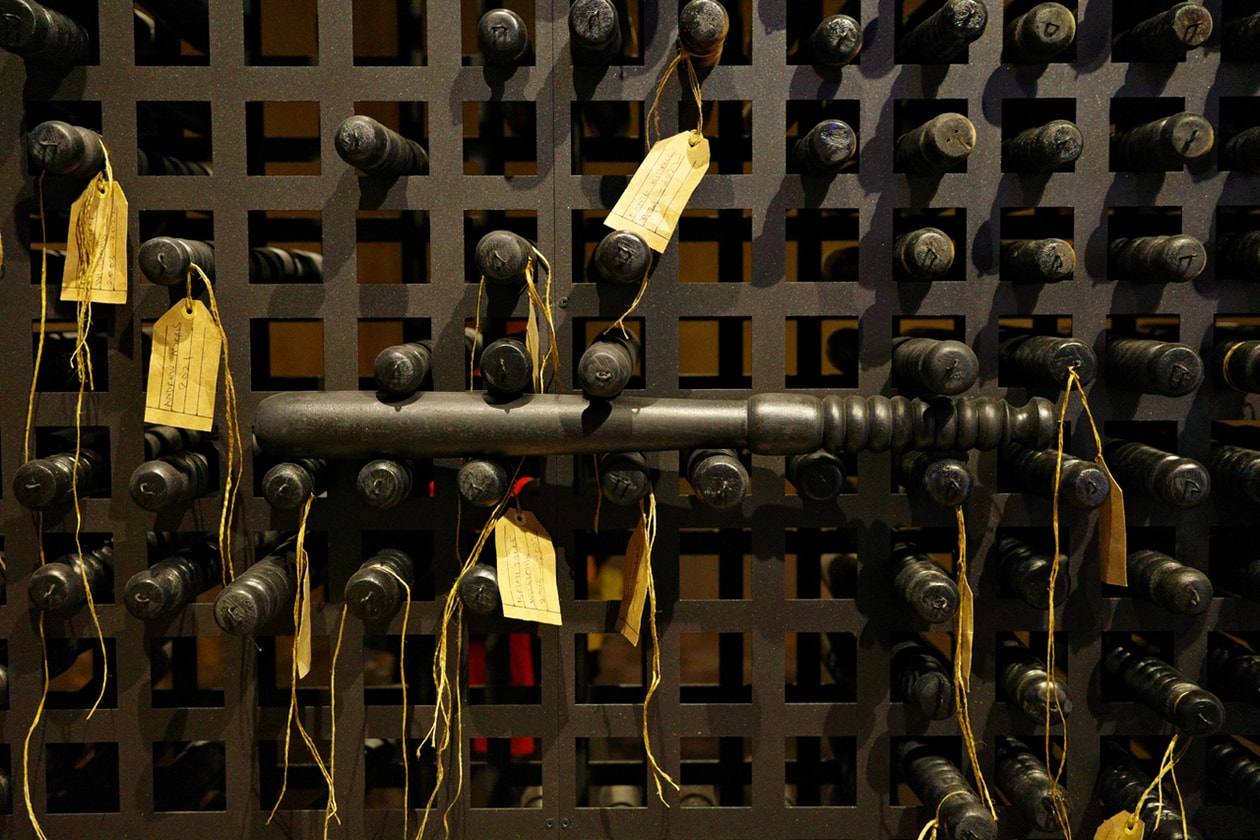

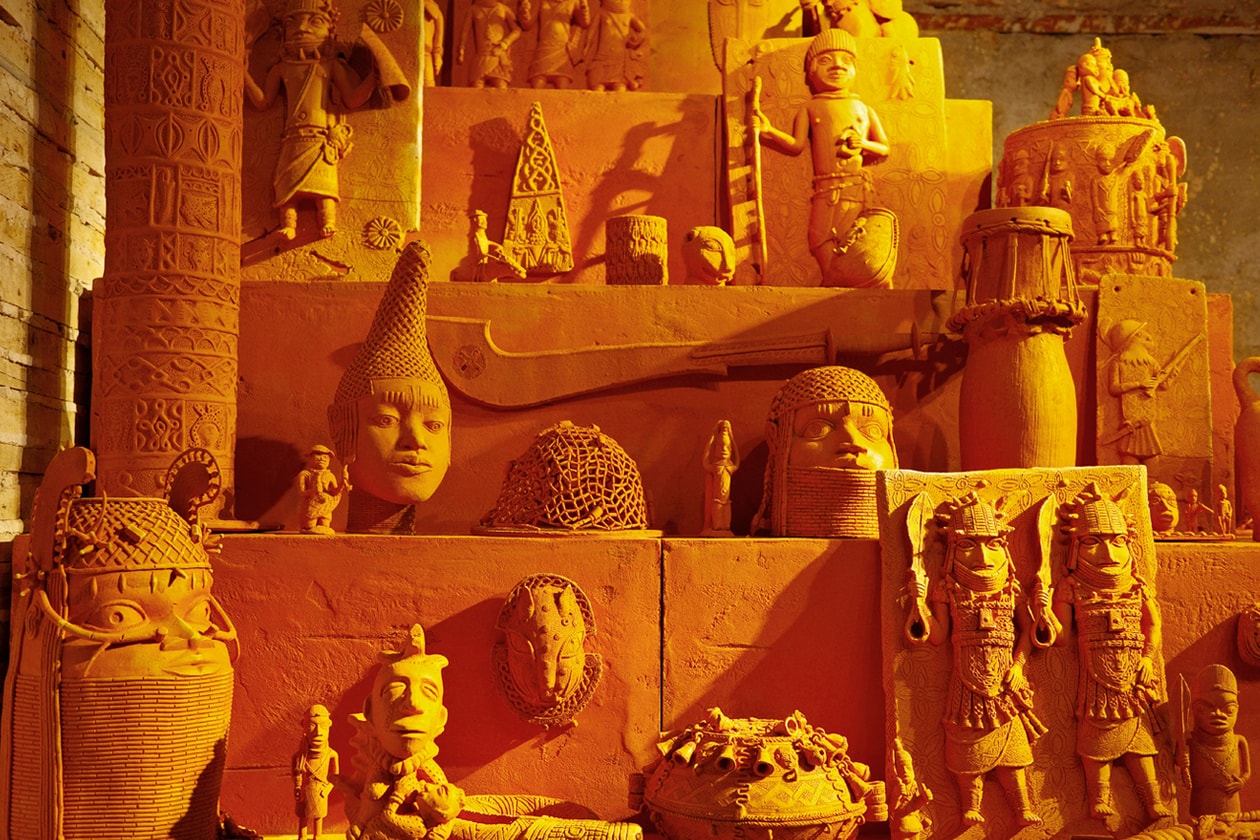

Nigeria

Instead of the Giardini della Biennale, Nigeria Imaginary takes over the Palazzo Canal and explores the West African nation, both in the contexts of history and the shape-shifting image formed in the mind. Curated by Aindrea Emelife, the exhibition spans painting, film, installation, sculpture and unique AR displays ruminating on moments of optimism within Nigeria’s past, as well as formulating “a Nigeria that could be and is yet to be,” according to Emelife.

Nigeria gained its independence from the UK in 1960, leading to an explosion of creativity in the optimistic post-colonial years — emblematic of the Mbari Clubs that formed shortly after, which served as “laboratory for ideas” where mythology, education and fantasy intersected. Artists such as Toyin Ojih Odutola explore what a world can look like if centered around the concept of the Mbari House, while Yinka Shonibare CBE RA revisits the legacy of the Benin Expedition of 1897, in which bronze sculptures and symbolic objects were looted and auctioned off to galleries and institutions around the world, such as the British Museum, amongst others.

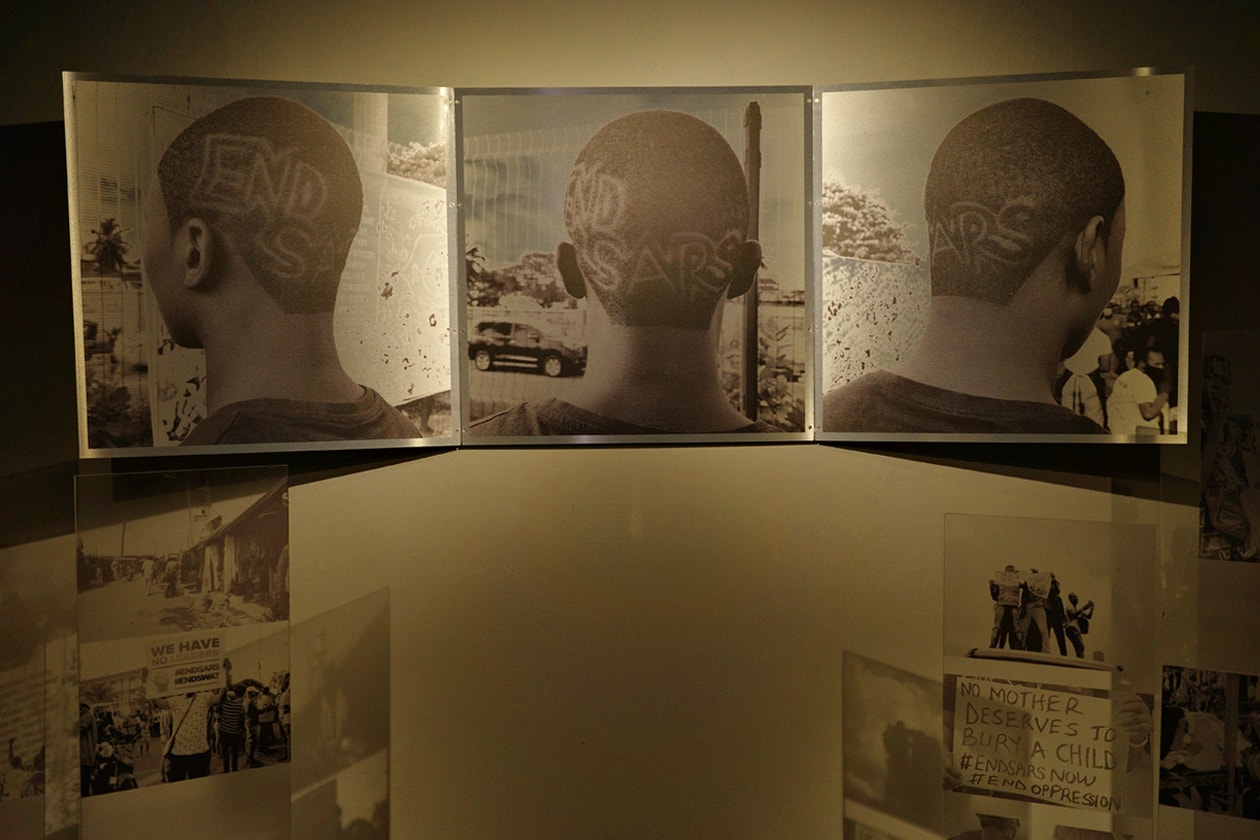

Further into the palazzo, British-Nigerian artist Ndidi Dike presents Blackhood: A living Archive (2024), a harrowing installation made of black coated steel batons that investigates the “intersection between global movements of police brutality: particularly the #EndSARS movement in Nigeria and the re-emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement follwoing the death of George Floyd,” wrote Dike. As it was following its independence, art today is a cornerstone in Nigeria’s reemergence as a nation. The creators of the Mbari house “considered art making a duty to a burgeoning nation and a vital public matter,” Emelife added. “It is here where Mbari and Nigeria Imaginary shake hands, passing on this duty to a new school of artists to reimagine a nation once more.”

USA

When Jeffrey Gibson, the American Mississippi Choctaw-Cherokee artist, was announced to lead the US’ pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, a major shift was signaled that would come to define this year’s exhibition. Dubbed Foreigners Everywhere, Gibson would be one of a handful of indigenous artists to lead major pavilions that probe into post-colonial narratives of identity and displacement.

“How do I relate to the United States?” Gibson told The New York Times, describing feeling at a crossroads of being the first Native American to represent the US in the Biennale’s history. His “complicated relationship” with a country that is supposed to be his home comes as no surprise. His grandparents were some of the many Native Americans forcibly displaced by the US government. Entitled the space in which to place me, Gibson created a vividly chromatic exhibition of sculptures, paintings and film installations that challenge the foundation that American mythology is based on, the ways in which it has actually been enacted, and proposing a future in which “indigenous art and a broad spectrum of cultural expressions and identities are central to the human experience,” said curators Kathleen Ash-Milby and Abigail Winograd.

Gibson and his 20-person team meticulously weaved intertribal aesthetics with European modernity, resulting in vibrant totemic sculptures and large geometric paintings that reflect on the past and current experiences of indigenous communities across the US. Another standout within the show includes a hypnotic multi-channel film installation, She Never Dances Alone (2020), showing artist and dancer Sarah Ortegon HighWalking as she performs the Jingle Dress Dance. HighWalking is shown twirling to a thunderous bass-house melody conceived by Native American electronic act, The Halluci Nation — her image multiplying as the film continues to embody the persistence of indigenous women across generations.