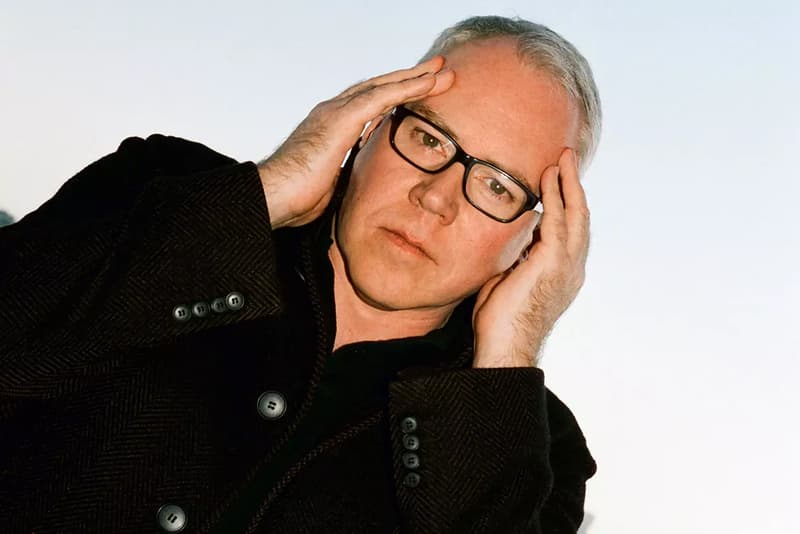

Bret Easton Ellis Talks Politics and Coming out With SSENSE

The ‘American Psycho’ author speaks up.

SSENSE talks to Bret Easton Ellis, American author, screenwriter and cultural icon known for work such as American Psycho and The Rules of Attraction. In the interview, the multi-hyphenate creative speaks about today’s politics, coming out as gay, and culture today. Read the full interview over at SSENSE now, and check out the retailer’s latest collaboration with Kappa.

Robert Grunenberg: Looking back at your career, do you feel success and fame at a young age is a burden?

Bret Easton Ellis: When you become well known, you’re kind of trapped in an image in a lot of ways. You stay frozen at that time, whether you’re a beautiful actress, a famous football player, a writer—I often think that I was stuck at 21 as this bad boy writer, and that people still look at me that way. They look at my work as all about youth, it defines me, it’s my brand in a way. I compare myself to a lot of my contemporaries who came of age in the 80s, and they’re kind of just all gone.

How was your coming out as a gay writer?

I never identified as a gay man. I happen to be a man of many interests, one of them was men. I was 6’1, I had this hair color, I liked this movie, I liked this kind of guy, I liked this kind of car—that was how I saw gayness for myself. It never defined me. It was just one in a series of things I had to deal with. I never had the torture of coming out. I didn’t care enough to tell my parents. I just lived my life. Certainly, it was easier where I was to live that life: Beverly Hills, Los Angeles. It was much more accommodating than say Arkansas. Certainly exploring my sexuality at Bennington College in Vermont in the early 80s, pre-AIDS, was nothing. Becoming famous, it became a little tricky. I didn’t want to be a gay writer. Because then you weren’t just a writer, you were a gay writer. That’s how it worked from the 80s, into the 90s. So, I played coy about it. I lived in the glass closet. People kind of knew, I didn’t admit it, but it wasn’t the closet. I didn’t pretend to have girlfriends.

Right. It wasn’t a big part of your identity.

I was never politicized by being gay. I missed the whole AIDS thing because I was too young, so that didn’t politicize me either. I was lost in writing for many decades, the 80s, the 90s, and a little bit into the 2000s. It wasn’t really until 2005 when I gave an interview to The New York Times that I officially came out. I didn’t think it was a big thing, it was part of a conversation where I said I dedicated Lunar Parkto my dead boyfriend, Michael Kaplan. So, I always felt gay culture was a ghetto growing up. I didn’t want what gay men were kind of forced into—into a neighborhood, into a gay club—it was never attractive to me.

How do you feel about gay culture today?

Terrible. The writer Tennessee Williams once said, the worst thing that could have happened to gay men was Stonewall, because pre-Stonewall, pre-politicization of gay life, it was kind of a glorious free-for-all that was a secret, a vast secret society of men always managing to find ways to fuck and meet each other. Once it became this kind of miserable, political thing, being a gay person meant that you were automatically ten things. For a generation of men, that’s when the fun went out of the room. There was also a danger, a taboo element, a mystique thing about it that I miss. I miss the idea of the gay artist as a radical trailblazer, that has been flattened out in our culture. We won’t have a Tennessee Williams, or Robert Mapplethorpe—there was a kind of intensity from a gay artist that was forced upon him by society, by these circumstances.