An Introductory Guide to visvim's Advanced Processes and Techniques

We take a look into how visvim pieces become qualitative rather than quantitative.

For years, Japanese cult label visvim has provided its customers with not only the highest quality product manufacturing, but deep, rich stories behind each product and its production. And while factories behind Hiroki Nakamura’s brand may have shifted from Japan and Korea to more recently China, both quality and the storytelling processes have not changed. The beauty is certainly behind the details and visvim prides itself on these truths; nothing less is expected of the 16-year-old brand.

The stories told stem from decades and even centuries of Japanese and American tradition in construction and manufacturing. From tanning to dyeing and even stitching, every garment within visvim’s collections is historical in meaning, but many of such are unknown or misunderstood by the general public. Therefore, we’ve decided to take a closer look at the core foundations in visvim’s advanced craftsmanship techniques and processes. There are far more production facts that line the vast history of visvim, but the below production schemes are certainly its most well-known and are expected to make a return in its near and extended future collections.

Indigo/Natural Dyeing

Implemented onto numerous products that carry the visvim label, Hiroki’s love for all things indigo is more than just a choice of color. Originating as far back as the 10th century, indigo dye sourced from indigofera genus of plants provided a strong economic backbone for Asia, as the dye was particularly difficult to obtain. Japan found processes, known as Kasezome, to extract the natural dye and incorporated it into kimono-wear and what we know today as blue denim jeans. Products are dunked into massive, skin-staining barrels of the liquid dye and dried for long periods of time to provide that vibrant indigo color that eventually wears away for gorgeous patterns and patina characteristics to the garment, and thus recording the consumer’s history with the item. Alongside indigo dyeing, visvim also implements a wide range of natural dyes that also are extracted from vegetable matter and trees for natural shades of red, yellow, green and more. Both techniques are thus synonymous to visvim, seen on its Social Sculpture denim, countless shirts, shoes, and even the underlying theme behind visvim’s concept I.C.T., short for Indigo Camping Trailer.

It’s important to know however that modern-day mass-produced indigo jeans use a synthetic dye rather than the extensive natural process.

Vegetable-Tanning

Vegetable tanning is a process that treats natural hides which eventually become wearable leather goods. The process begins with the sourcing of tannins, or a biomolecule that bonds to the hides in order to kill off the organisms within before the material is ready for daily use. Once the living organisms are killed, the collagen fibers, or proteins, are left and thus are ready to be produced into jackets, shoes, accessories and more. While practices such as sun-drying hides provide an alternative to the extensive process in question, vegetable tanning thus provides the leather with a beautiful sheen and a level of breathability that is highly favored and incomparable. With modernization comes efficiency, and thus vegetable tanning has been replaced by chrome-tanning; a synthetic procedure that provides similar effects with a less demanding time frame and cost to that of vegetable-tanning using tree and nut tannins. Today, tanning of hides using synthetic compounds accounts for a large majority of leather production–visvim’s use of traditional vegetable tanning remains within the brand’s core ethos for a wide range of products.

Textiles and Embroidery

Japan’s use of woven fabrics and textiles dates back to its rich history of kimonos and workwear, utilizing materials and fabric patterns to tell its story of production and manufacturing, while also distinguishing styles from garment to garment. For visvim, the intricate designs found in its woven products, for example its highly popular SUMMIT PAPOOSE backpack, give a sense of unrivaled design aesthetic that naturally gives each product a unique “one-of-one” texture. Its process stems from traditional weaving looms — much like looms for selvedge denim — that both efficiently produces large amounts of usable fabric while also providing a rigid, durable medium that organically contains desired “character”-defining flaws within its weave.

Another widely adopted practice is that of Japanese sashiko, or traditional running stitch embroidery. The island country’s practice of sashiko — translated directly as “little stabs” — was common in repair needs but was thus adopted as decoration shortly after due to its distinctive look of white or sometimes red thread across indigo blue fabrics. The stitching not only displayed an eye-catching geometric look, but it also provided reinforcement to the garment thus adding durability as originally intended.

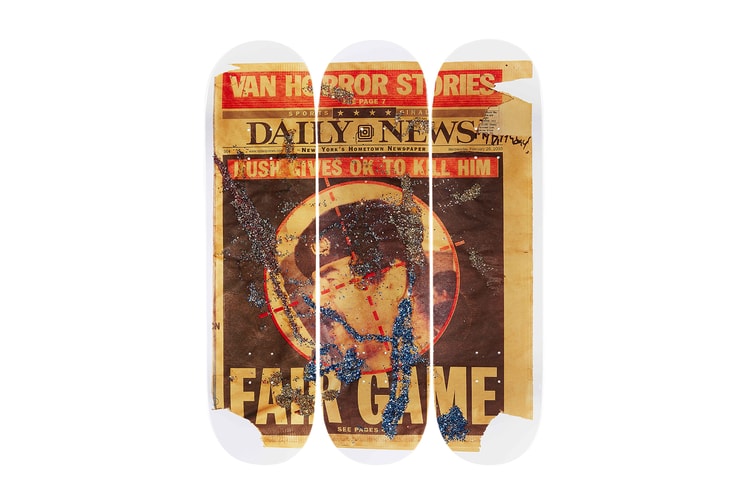

Hand Drawing and Painting

Some things are best left away from machine manufacturing, and visvim’s use of hand work products embodies the time-honored practice over efficient printing and screening of graphics. While the brand has only recently begun to truly highlight the practice (widely seen in its Spring/Summer 2015 collection), its appeal has set specific products apart from the “standard” (used loosely) offerings and finds aesthetic value through wabi-sabi — “beauty in imperfection.” The labor is painstaking and the output is incredibly inefficient, as 2015’s season saw hand-drawn T-shirts and water-colored embellishments that took multiple artists to complete and hours logged for completion of a single piece. The quality however, while seemingly low to the untrained eye, provides a sense of individuality that only hired artists possess and a personalization that dates back to “kyo-yuzen” kimono painting techniques of expressiveness and charm.

Goodyear Welt

Originally invented in the 19th century, the process of Goodyear welt construction provided footwear with a level of breathability due to the lack of impermeable adhesive; the upper, welt, and midsole would be hand stitched together allowing for moisture and airflow to escape through the crevices. The construction was however strong enough that it allowed for the thickest of leathers to be bonded to its respective soles, in exchange for a ton of a constructor’s time and elbow grease. Combine the vegetable-tanned leather of visvim’s famous Grizzly or Serra Boots with natural cork footbeds and rugged Vibram soles and the label’s “FOLK” nomenclature was a synonym for the highest quality shoes and boots to ever release under Hiroki’s direction. Further, as an added bonus, visvim also allows for FOLK footwear soles to be replaced at the consumer’s request — the lack of an adhesive allows for removal and replacement repairs to be fairly straightforward.

visvim will present its Spring/Summer 2017 collection on September 7 in New York during New York Fashion Week. Stay tuned for a closer look at the products utilizing the above processes shortly after.