HYPETRAK Magazine - Volume 1: Flying Lotus, The Illustrator

Steven Ellison, commonly known as producer Flying Lotus, is preparing for the release of his

Steven Ellison, commonly known as producer Flying Lotus, is preparing for the release of his forthcoming fifth studio album, You’re Dead!. The title is a testament to Ellison’s fascination with death, even going so far as requesting acclaimed guru manga artist Shintaro Kago to create the album’s cover art. However, You’re Dead!, in the context of Ellison’s artistry, comes across as more of a rebirth than an absolute end. Where Ellison’s earlier work featured little to no guest appearances, this album features contributions from frequent collaborator Thundercat, as well as Herbie Hancock, Kendrick Lamar and Snoop Dogg. When the You’re Dead! teaser video released in August, which featured Kago’s surreal imagery of decapitated, skinless bodies synchronized to short bursts of intricate, jazz-influenced melodies, it indicated one thing: Ellison would be returning with some of his most ambitious work yet. Although two minutes long, one could hear the growth in Ellison’s music –- still challenging and complex, but definitely more direct and focused.

The music is only one component to Ellison’s artistic vision. Before devoting himself to music, he went to film school and was inspired by national and international filmmakers alike: Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers, Takashi Miike and Lars von Trier. Such filmmakers continue to influence Ellison as he bridges the gap between auditory and visual art. One can see this as early as the music video for “Zodiac Shit,” a notable track off Ellison’s highly acclaimed 2010 Cosmogramma album. Since then, the visual accompaniments to his music have only become more compelling and intricate. It is still difficult to watch the short film for his 2012 Until the Quiet Comes album and not have goosebumps from the scenes of a child’s blood flowing like a river, or a young man being revived for one final dance before journeying to the afterlife. Like any good composer, Ellison creates a mood for his listener, and the visual component ensures that the mood settles in.

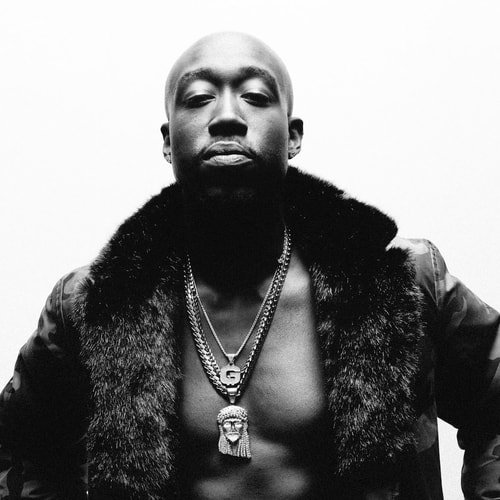

Along with his work as Flying Lotus, Ellison has also begun to create more material through his rap alter ego, Captain Murphy. When Murphy was first introduced on the Flying Lotus- produced track “Between Friends” in 2012, people speculated that the mysterious rapper was either Tyler, the Creator, Earl Sweatshirt or Ellison himself, or a combination of all three because of the frequent pitch shifts in vocals. Ultimately, Ellison revealed himself to be Murphy at a Low End Theory show, celebrating the deluxe version release of Murphy’s debut mixtape Duality.Ellison’s relationship with art has played a fundamental part in his own artistry. Like Kago, Miike, Tarantino, and the other artists he references throughout this interview, Ellison enjoys pushing the boundaries of this discipline. This is what motivates him: the ability to challenge his own ideas (as well as those of his listeners) of what art can be, and how other forms of art can complement one another. Even now, with the recent unveiling of his new live visual set up, Ellison continues to explore his artistry through interesting and alternative means. It seems as though the filmmaker in Ellison is still present, directing a creative world that is just as compelling as it is complex.

There’s no end for Ellison –- at least not yet. It seems that he’s finally at a place where he can truly explore his creativity through means both in and outside of music. Ellison might be fascinated with death but his artistry is very much alive: always moving forward, never stagnant.

When was the first time you mixed your music with visual art?

When I mixed music and visual arts for the first time, it was just for my own stuff I guess. Back in the day, I experimented with films, videos and that kind of stuff, which was kind of my first introduction to it. I think that it made one love the other. I love music, but now it’s hard to imagine doing music without visuals to accompany it. And as far as the way I work, it is always a very visual thing, even if it’s with a music program.

When you first started, was it more the visual that pushed the music, or vice versa?

For a time it was all about the visuals. I went to film school and became really interested in making cinema, and eventually I got back into making music heavily because it was so hard to make films by yourself. But I like the fact that I can be alone and make music, and get introverted and very detailed with my own personal ideas without meeting a whole crew of people and actors.

What were some your inspirations in terms of cinematographers or artists?

When I was inspired by films I was really into a lot of Japanese filmmakers. Artists like Takashi Miike, Tekeshi Kitano and all the crazy filmmakers who were doing things a little left field. Even someone like [Quentin] Tarantino. At the time I was really into the guys who were going in the other direction. When I was in film school it was around the time of the independent cinema revolution which saw guys like the Coen Brothers, Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino, not to mention all the new European cinema filmmakers who were coming out like Lars von Trier. For film, it was like the new wave –- the newest generation of filmmakers that will be remembered forever. It was more inspiring to me than music because at that time, it was the shining suit era of music (laughs). I felt as far as telling stories and incorporating music and visuals go, film was the most attractive medium to me. But the music just kind of happened. I was pursuing filmmaking, but all the while I was producing hip-hop and that took off.

How did you know manga artist Shintaro Kago was the right choice for creating those 19 cards on your website, and where did you see the connection with him?

I’ve been a fan of his work for a while, and I really appreciate his style of storytelling. He could do short stories, building these worlds that don’t exist and are completely impossible, but yet believable, and he can also tell stories that transcend his medium. This approach is really attractive to me so I became a fan of his work and bought some of his artwork directly from his website, and then just started chatting to him a bit. He seemed really approachable. When I was starting to come up with visual ideas for the album, I’d always refer to a specific piece of his in my house. I said, “it needs to feel more like this!” And I thought, “you know what? Why don’t I see if he’ll be down to do something?” So I just hit him up –- I have a friend who speaks Japanese who helped me translate my thoughts and ideas, and we kept talking all the time with Kago to get things going. He was so great to work with and he worked so fast. He did those 19 cards in a week.

In your own words how would you translate your album cover?

I’ve seen a piece that Shintaro Kago did, and it’s a theme he does in his work, with the characters having an empty hole in the head. There was something about that I wanted to have. I wanted to have that moment of realization, you know? “Oh I’m dead, I’m not even me anymore.” On one of the songs I did on the record it talks about having a bullet in my head. I just wanted to repeat some of the themes, and how your identity is gone. I really connected to that because I didn’t want it to feel gory either. I didn’t want the album to look bloody. But at the same time, I felt that it was a good way of playing into the religious themes and ideas of mandalas, and the tunnels of light. Not to say that I believe that’s what it is, I wanted to play off of people’s perceptions of what happens in the next life with the visuals as well.

How important to you is the art component for a music release?

It’s funny, man, because a lot of people don’t care. A lot of people just don’t get it and a lot of people just aren’t visually inclined, and in this day and age you don’t have to be. But to me, I always see it as an opportunity to tell my stories better, and to bring people into the world of the album I’m trying to create. Whatever it is –- single, EP, album –- I always try to be considerate and careful with the artistic choices because it helps to tell the story if you get it right. In this case specifically, I have been very hands- on with every bit of it. I even decided on the font. The actual text and everything else is very important, especially with an album named You’re Dead!, it’s easy for someone to take the concept and go the wrong way with it or turn it into something that it’s not meant to be. So it’s really important for me to make sure that the stories are represented right throughout the entire campaign, because one minute it could look like Scooby Doo (laughs), and the next it could look like a death metal album. I needed it to feel a certain kind of way throughout in order for it to resonate with people and to make sense. I spent so much time on all the other aspects of it so I want to make sure that the things the people see from the branding to the design is all a consistent thing. When I was a kid, I paid attention to things like that. All the things that I loved, all the things that I was a geeky fan of, I always paid attention to the finer details. When it’s done well, it’s like people don’t even notice, but when it’s wrong, people say, “you know, there’s something wrong with this.”

Switching to the topic of music, what lessons did you learn from collaborating with artists like Herbie Hancock, Snoop and Thundercat?

I learned that you can’t really go into this kind of collaboration with a planned outcome. I feel like for a long time I’d be hesitant to collaborate with people because I didn’t necessarily know what to tell people sometimes, or I didn’t know how to communicate musically with people, especially trained musicians. I wasn’t confident enough to do that. This time around, however, I felt a lot better having done it a few times already on records now, so I was more at ease with the collaborative aspect in terms of just trying to relay ideas to people who can read music, but also having to adapt to someone’s style and how they do their best work. That’s what I always try to chase after, what do I like about this person? Working with Herbie Hancock is really intimidating if you think about it, but it never felt that way. It felt very organic, the way it all went down. A lot of that had to do with working with Thundercat, because he and I have a great rapport and we can make music without even talking. So it was cool to have him as an ally.

For the full story, pick-up a copy of the HYPETRAK Magazine: Volume One for $12 USD over at the HYPEBEAST Store.