Shohei Shigematsu thinks architecture needs a refresh. “Architecture globalized quickly and became very generic everywhere,” he tells HYPEBEAST. Throughout his illustrious 22-year career at architecture firm OMA, Shigematsu has been focused on researching areas that others often miss in order to facilitate the progression he feels is necessary for the industry.

“[Architects] need to stay relevant in society. In order to do that we have to develop our own way of looking at the world,” he says. Along the way, Shigematsu has discovered the many unexpected relationships architecture has with food, fashion, art and even economic recessions.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Manus x Machina exhibition, Albright Knox-Gundlach Art Museum’s new gallery space and the upcoming Audrey Irmas Pavilion are just a few examples of how Shigematsu and his team are creating architecture that propels the industry in a new direction.

The Albright Knox museum in particular exemplifies how Shigematsu looks beyond the standard architecture brief; for that project, he considered how museum culture is shifting to become more accessible to the wider public. The result is a gallery encased in a glass shell that exposes large-scale installations, performances and events happening within the museum to outside onlookers.

During a visit to OMA’s NYC office, HYPEBEAST sat down with Shigematsu to learn more about how fashion and architecture can benefit from one another, the future of urban landscapes and the difference between iconic spaces and iconic architecture.

You’ve been at OMA since 1998. Why OMA versus another firm?

At the time, Rem Koolhaas was becoming a world-known figure. But beyond that I always wanted to do something that creates a conceptual approach to architecture, and Rem was really at the forefront of that kind of thinking. I didn’t think I could get into OMA when I applied. I was lucky that there weren’t many Asians at the time. I’m not saying that I was chosen because I’m Asian, but to some degree, yes, because there is a level of diversity all offices aspire to have. When I got in, I was lucky enough to be able to work on many design competitions. It was very intense, but at the same time, I had great exposure to Rem and project leaders.

During your decade as a partner at OMA, have you noticed any major shifts in the architecture industry?

When I started here at the New York office in 2006, we were doing well until the economy crashed in 2008. I think that moment changed a lot in terms of how people perceive architecture and how the investment works. For example, I think there is now a lot more social dimension required in any kind of architectural project, with community engagement and also on the client side, to have more consensus with society. I think this also led to more landscape architecture. I also noticed that during the recession, a lot of young architects went on to a different path because it was difficult to get a job in architecture at the time.

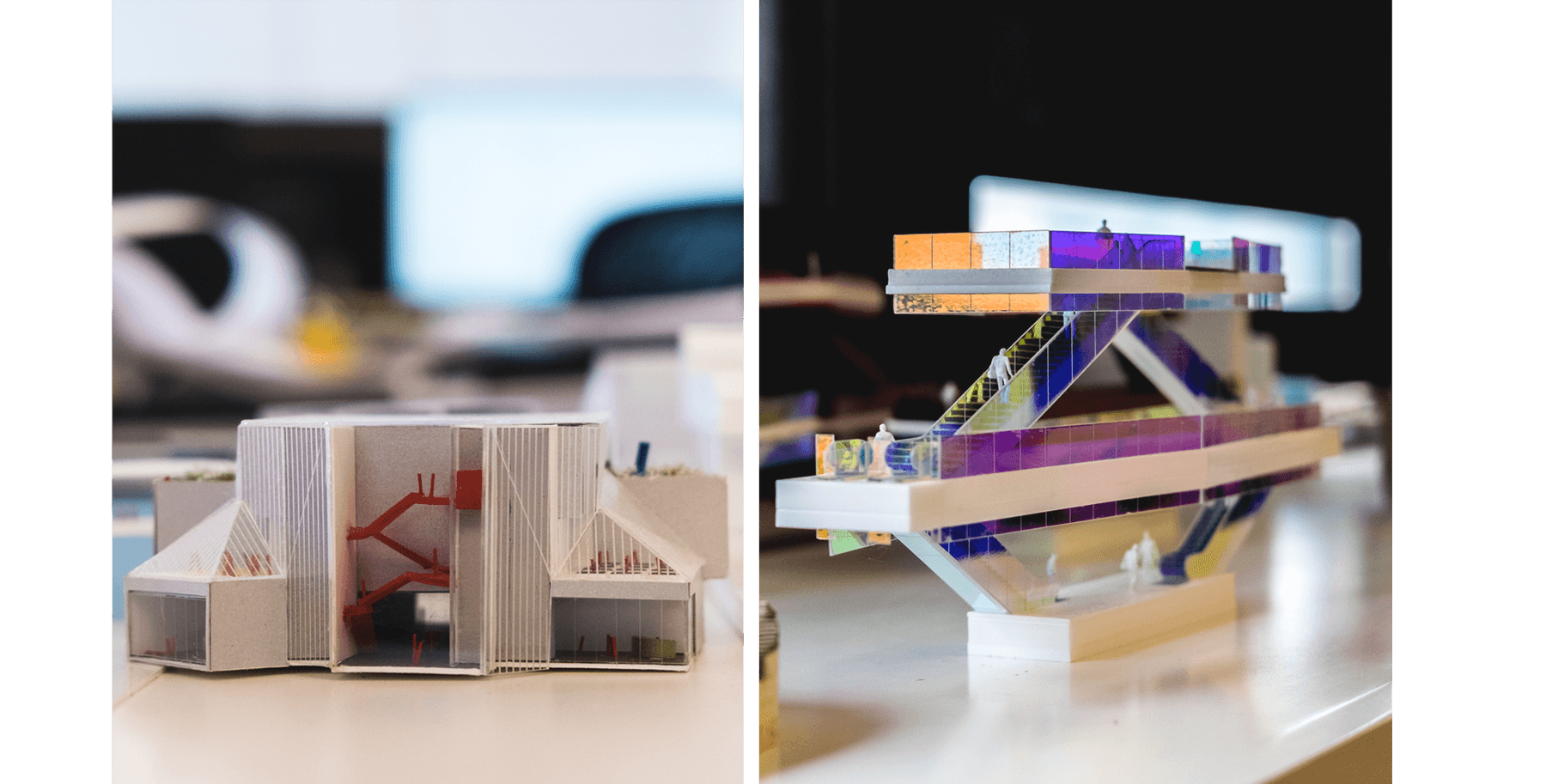

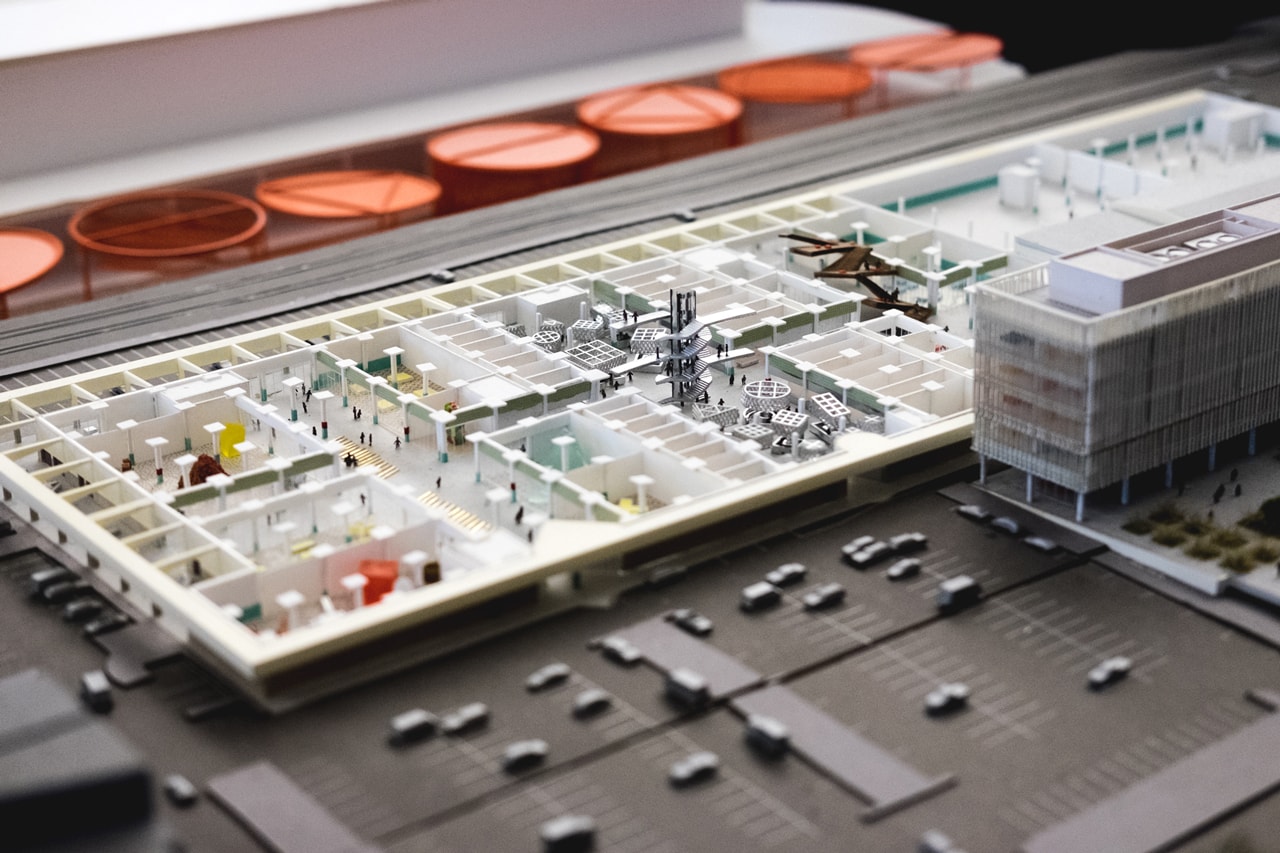

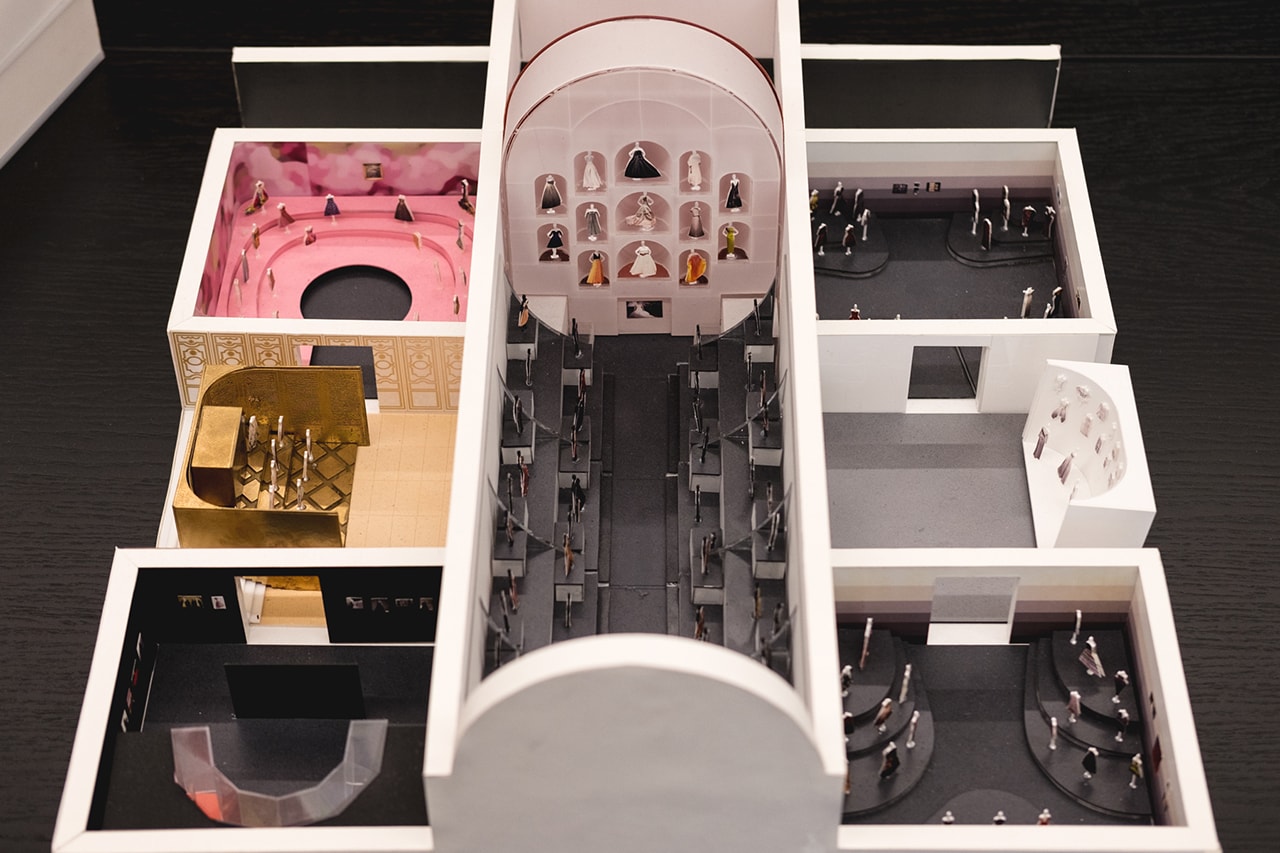

You work on so many different types of projects and exhibitions. Besides making miniature scale models like the ones throughout this office, are there any constants in your design process?

We would like to believe that there is some level of consistency in the way we develop projects. And there definitely is, but it’s always a little bit different depending on the project and the different typologies and cultures we may be working with. We work across North America, Latin America and Japan, so of course the different cultures have different highrise regulations, submission process and so on. But what’s important is that there’s always an overarching belief or philosophy that tries to observe general shifts in the world.

We also use institutions when we teach to further investigate what we are interested in. I actually did a study about crisis — not just limited economic crises like the recession, but also natural disasters and the effects they have on architecture and urbanism.

We also studied the art world by looking at art fairs and biennials and how they are changing the “Bilbao effect.” Bilbao Guggenheim actually changed the mentality of municipalities because everyone suddenly wanted an “iconic” building. But that idea somehow ended around 2008. We looked at how these fairs and biennials are actually taking over a more static architecture because the events are more dynamic.

“I’d rather create an iconic space than iconic architecture because if it’s an iconic space, it will be loved and it will last.”

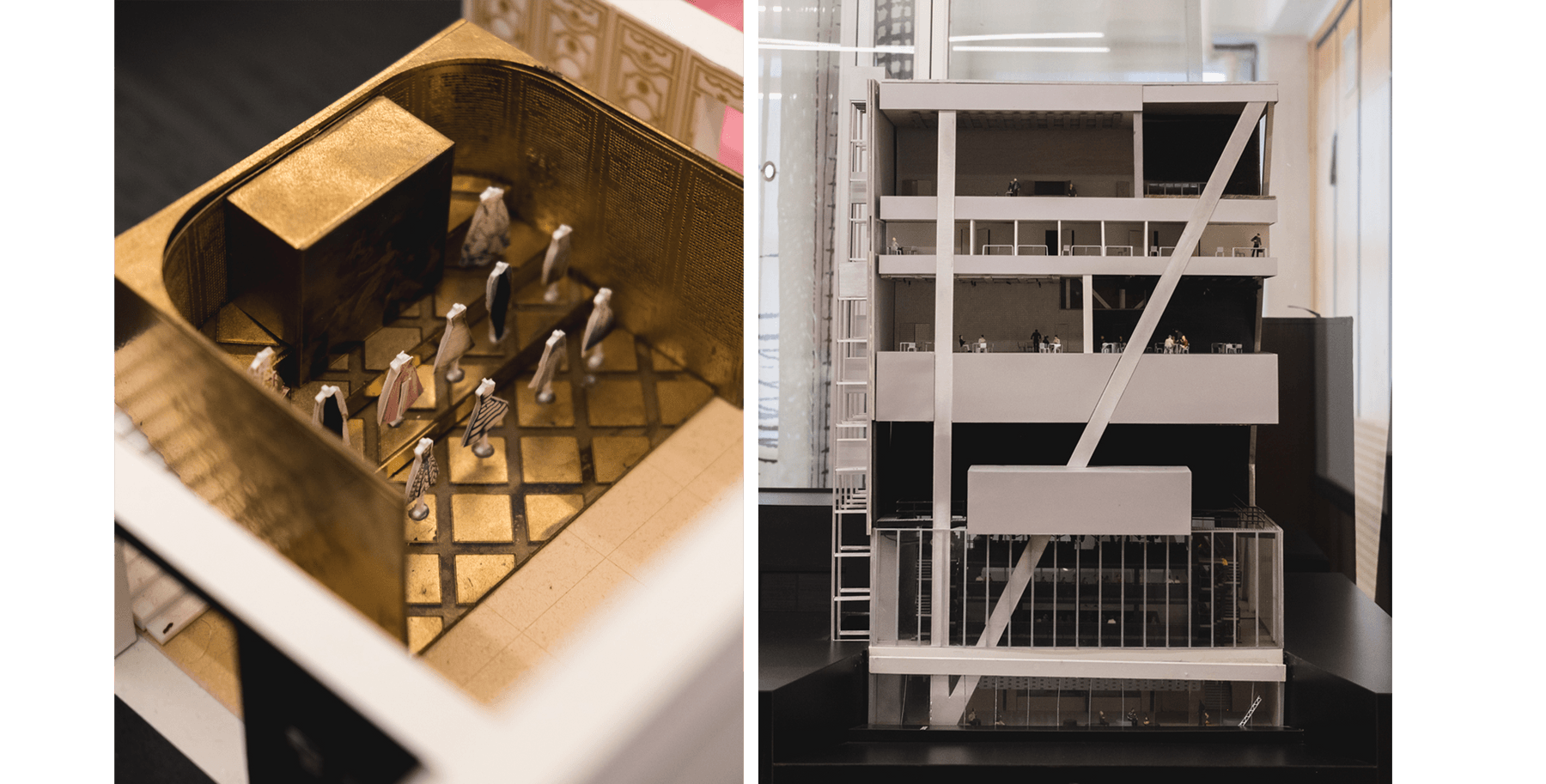

You work very closely with museums and galleries. Are there any special considerations you have to take when you’re considering how art would fit within a space you design?

On one hand, I would love to inspire artists. On the other hand, I cannot break the standards and the customs that have surrounded the art world for a long time — like how a typical gallery space works.

In our recent museum projects, we decided to add an extra space that is not purely a gallery space but also a publicly accessible space where a lot of improvisation can happen by artists, curators or the public. The art world is changing. There is a lot more performance art, large installations, collaborations and community engagement.

Museums tend to be closed off because the best gallery spaces need four walls and some type of skylight. But on the contrary to that architectural need, there’s a social pressure urging museums to be more open and more socially engaged. So there’s a tension between the perfect gallery space versus an institution that needs to be more open and transparent. As architects, that is what we believe we’re articulating.

We did this for the new building we created adjacent to the already-existing Albright Knox Art Gallery. We wrapped the gallery with a glass envelope so that you can actually use the space around it for installations, projections, galas, etc. It’s a very cold climate there, so the glass also allows you to appreciate the surrounding Delaware Park without going outside. It really changes the image of the museum because it used to be very closed and very authoritarian, but now the activities are much more exposed to the public like a community space, which captures one of the major changes that is happening within the museum institution.

I come from a fashion background, and I always think architecture is so fascinating because it’s so slow — you guys have to think incredibly far ahead.

I can honestly say the entirely opposite comment: We are so jealous of the fashion world because it’s so fast. That’s why collaboration between fashion and architecture is so important. It’s very important for architects to understand the speed and creativity of the fashion industry, which, as you said, is very different from architecture. I think that by understanding the different speed of fashion, we can enrich the speed of architecture too. You can be more playful and frivolous with certain things like you can with fashion, while certain things we have to keep more traditional. That kind of balance actually generates architecture that is currently relevant but also relevant for the future.

But we never actually think, “Okay, this building will last for 2,000 years.” We don’t really design like that. To some degree, architecture has become a commodity because the lifespan of a typical building is around 50 years. In Asia, that timeline is on the shorter end, and in Europe it’s longer because there’s a tradition to reuse old buildings longer. But current buildings that are built recently are not meant to last — like buildings with stone.

But what matters is that there is a complete synergy between a building’s design and the building’s operation. If a building Is loved, it will last longer. It’s not about the material. If it is loved, people will always renovate and take care of the building to make it last longer. There are wooden buildings that have lasted for over 2,000 years in Japan even though wood is not considered the best material for longevity. For me, it’s most important to consider the longevity of a building and to design it with operational issues and users mind. I’d rather create an iconic space than iconic architecture because if it’s an iconic space, it will be loved and it will last.

“Modernists truly believed that architecture could solely resolve social issues. I think that’s probably why modernism failed.”

At a presentation you gave at the Lexus Design Award mentorship program in 2019, you spoke about the importance of mixed media in your design process. I specifically remember watching a video your team submitted to an architecture competition, which is a pretty rare format for firms to submit with.

Mixed media is one of the most important issues of our generation. Submissions used to be drawings and models, but now it’s a PowerPoint and there’s room for animations and video. In a way, every rendering looks the same nowadays, because, of course, clients look for the most realistic representation of your architecture. So there is no distinguishing factor between Office A and Office B. Now that every representation of a project is more or less the same, how do we show our originality? And if the building itself is original, how do we translate that to its representation? These are big challenges for us that we would like to push further.

There was a moment when architecture was becoming less relevant to society because architects were — and I still get this — often considered very stubborn, artistic and difficult to deal with. We of course value our own personal obsessions and personal expressions, but we also need to stay relevant in society. In order to do that we have to develop our own way of looking at the world. That’s the way we can create an interesting framework for architecture.

You’ve been a mentor for Lexus Design Award finalists for two years now. Why work with a competition that is for designers of all fields versus just architecture?

Becoming a mentor stems from my interest in how the word “design” is being used today and how design can now become part of the business world and monetized. Of course design can easily be monetized, but it can also make societal things happen that go beyond currency or money, so I’m also interested in learning more about how design is being developed and how the industry itself is transforming.

I’m also interested in how companies have slogans like, “let’s make a better tomorrow” or “let’s save the world” as a corporate responsibility. But can design really save the world? For me, my answer is probably no because the idea that design can save the world is very similar to the notion of modernism, where modernists truly believed that architecture could solely resolve social issues. I think that’s probably why modernism failed to some degree.

It’s very dangerous to tell young designers that the best design is the design that saves the world. It’s a little bit of a trend right now for tech companies to design to save the world. It’s, of course, important, but designing a good book or designing a good chair leg is also important. It’s very unfair to charge this young generation because our generation failed. It’s unfair to say that they can’t just be a good furniture designer.

What excites you most about your job right now?

I think the sheer diversity of people I meet and the places I go. One day I go to Mexico to do a bridge after an earthquake and the next day I’m at a museum gala with a bunch of rich donors. That diversity exposes me to so many things. I’m able to keep learning and keep absorbing different ways of thinking throughout the world.

I feel like I’m becoming more and more open as I work more. It’s actually quite exciting and liberating. I know it sounds like a motivational speech, but I think it’s very important to create my own drive and my own philosophy. Being open is one of the most important states of mind for our generation.

OMA’s research division, AMO is having an exhibition at the Guggenheim this month. Are you involved with AMO?

Yeah, we set up AMO when we started to work with outside industries like fashion and tech as a way to formalize the research we had already been doing as an entity within the company. AMO has been a very strong drive to create a dialectic relationship between architectural and non-architectural thinking. Now we simply consider AMO a part of what we do. We all think, and we all do research.

“We need to create a new city that is relevant to our new future.”

Is that where your research on the relationship between fashion and architecture fits within OMA?

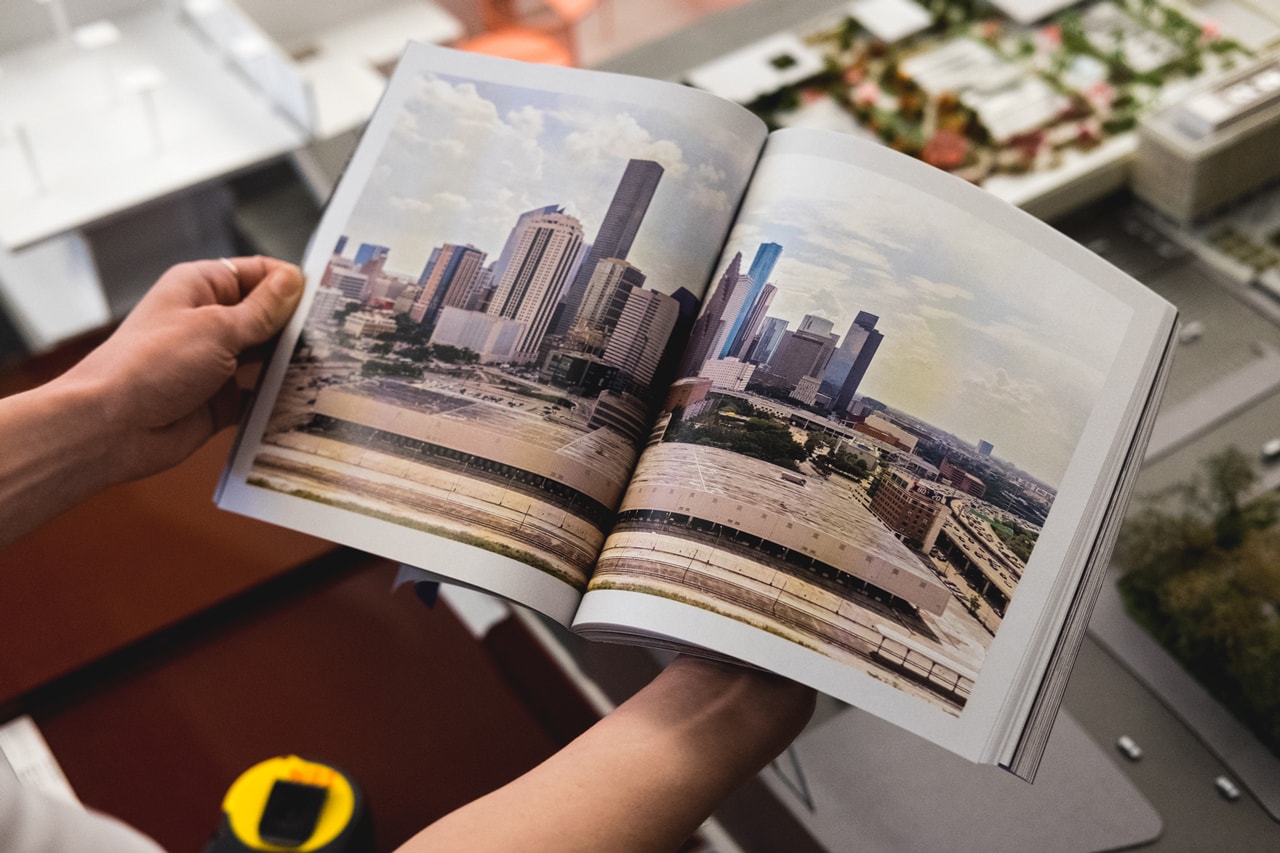

Yes, but oftentimes it’s tough to do that type of research in the studio because there are commissions to focus on, so we collaborate with institutions. For example, I researched architecture and urban design through the lens of food for Harvard. They asked me to come up with a design studio theme that could last three years because they were interested in the continuity of the studio, so I came up with Alimentary Design.

Architecture has become very generic globally, but food is still diverse and very region-specific. Champagne can only come from the Champagne region of France, etc. Food can be both very local and very global at the same time, which I thought we could learn from because it’s so boring to be in a homogenous world.

At this point, food production has been pushed away from cities. Frank Lloyd Wright made a city called “Broadacre City” in 1958 where each inhabitant had to have a piece of agricultural land. Today, this is actually happening in China because its agricultural need is growing as its cities grow, so cities need to merge with agriculture. You probably get a lot of frogs and insects there, but at least you know that food production is part of your fundamentals. Studies show a lot of kids in cities think that cows actually lay eggs because milk and eggs are next to each other in the supermarket. This is just a consequence of food consumers and food producers being so far apart.

We tend to think that the ultimate outcome of human intelligence is a city like Paris or New York City. But I think we have a responsibility as our generation to design the next city. New York City is nice, but I don’t want to believe that New York City is the ultimate end of what a city can be. There needs to be progress. We need to create a new city that is relevant to our new future.

Photographer

Keith Estiler/Hypebeast