What’s the secret to a successful studio? Is it powerful name or a lifestyle brand? Do you really need a staff of 20-plus to accrue blue-chip clients and once you hit that mark and are speaking to the masses, how do you stay true to your own voice and continue to push boundaries? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, but Public-Library believes the best first step is to work through fear.

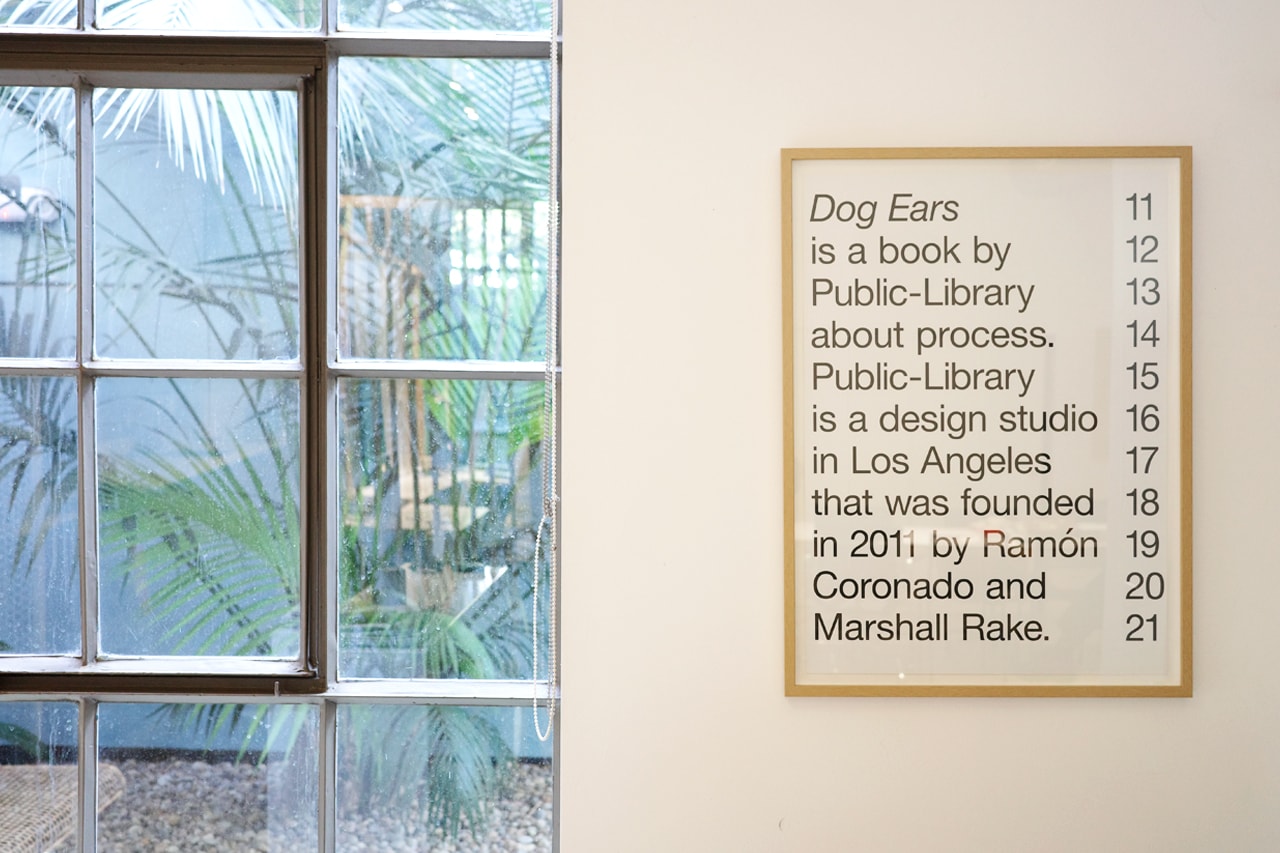

Founded by Marshall Rake and Ramón Coronado, the Los Angeles-based creative studio begins each project by reducing every brief to its core elements. The two, alongside their creative operations manager, Jeanha Park, begin to deduce meaning through a constant process of experimentation, all the while keeping a sense of wonder and allowing uncertainty to dictate the final result.

Celebrating ten years since going full-time, Rake and Coronado have never looked back and their client list, which includes Nike, Boeing, The New York Times and Sony Music, is a testament that fear can be used as a valuable asset when seen as a motivating force, rather than a crippling emotion.

For the latest HypeArt Visits, we visited Public-Library at their studio in DTLA. Read our exclusive interview below and let us know your thoughts in the comments section.

“‘That wasn’t the exercise, it’s cool, but not what we asked for.’”

Going on 10 years now. Take it all back on how you two first met and the genesis of the studio.

Marshall Rake: We originally met in college by having some classes together. Our work was always in a different spot than our other classmates. I personally found myself being pushed by what Ramon did and was doing stuff that I thought was really inspiring. So trying to connect with that and push that. During that time, we both really fell in love with typography, which is a backbone of the studio. We also both did things before design, so that led to us looking at it differently as well.

Ramón Coronado: In school, it is interesting that it was always Marshall and I — where we were almost picked on the side, ‘what the fuck are you guys doing? That wasn’t the exercise, it’s cool, but not what we asked for’, haha. I think that was really fun in school to push the boundaries and try different things. We’re here to learn and there was a lot of exploration that we did in school that was the foundation of the studio.

Marshall, you mention there were other passions that fed into your creativity outside of design. What were some?

MR: Before design, I was playing in crappy bands then designing all the t-shirts, CD’s, flyers and stuff. After a while, people stopped asking me to play guitar in the band and started asking me to design, so I was like, ‘Ok, maybe we should switch over.’

RC: I thought I wanted to be an architect. So after high school, I enrolled into architecture classes and just hated how long the projects were and the never-ending rounds and months of working for the same home. I was working on a small architecture firm. Like Marshall, I got a copy of Photoshop seven, I think it was, and started making these really shitty t-shirts and random graphics that didn’t really mean anything, but it was fun.

MR: If you’re not selling t-shirts in high school…

… did you actually go to high school?

RC: Hahah yeah exactly. But yeah I started a dumb t-shirt company and it was great just slanging them out of my buddy’s truck. We tried to do a trade show out in LA and dumped all our profits into it, but only sold one. It was so terrible. We both also come from small towns — Marshall’s from Kansas and I grew up in the Palm Springs area. It was really eye-opening to go from that world and try to come out with a cool brand and that’s how it died haha.

“It’s never been easier to have something look fine.”

What was the brand name and what year in college was this?

MR: We started in 2006 in college.

RC: My brand was called Function.

It’s a cool name, there are so many labels with bad names. Even in high school, where you don’t really know anything and you see your friend’s brand, thinking, ‘this sucks.’

Totally and I think this was 2004, so before college at Art Center.

So much has changed in the design world where there are these superstar studios, where designers have become regarded as artists in their own right. What have you noticed, having been entrenched in the game over the years — from design trends to observations on the field now — since you were in college?

MR: This is going to sound old, but we used to have to look things up in books. You’d have to go to a library or a design bookstore and find the Sagmesiter book or whatever you were looking for. Now, it’s so easy to see everything. Trends are out of control because it’s so easy now and the software has gotten so much better. The easiest thing for a designer is make something look cool — it’s never been easier to have something look fine. So there’s more fine stuff than ever.

You see a lot of agencies or a lot of studios that can do that and then whatever’s on trend, they can knock it out, because software is more proficient, people are more proficient, and you’re just more visually aware, because you can get onto Pinterest and go down a rabbit hole, see everyone’s stuff in the world and make more things look like that.

But I think what you see now, is that the people who don’t do that really pop. Like you said, the people who are more like artists, you see that, because they’re approaching it as an art, rather than something that’s on trend. As we all know, if you’re making something based on a trend, then it’s already dead. If you’re reacting to something you’re seeing, it’s already done. So you see people going against the grain and that’s the work that actually has an impact.

That’s something that we really strive to do. Just make the stuff that we want to make and be inspired by. We always say: the thing that we make with a client or collaborator, should look completely different that if they did it with someone else. If the three of us made something? Then it should be completely different than if the four of us made something, right? Because we should actually be reacting to each other’s personalities, point-of-views, tastes, backgrounds, histories, and then make something different, rather than just a cool logo, cool color palette or everyone’s doing this type of illustration. For us, what’s the point of doing that?

RC: Which is a very common brief haha.

“We want to be that building providing those different books.”

Can you talk about the concept behind the name, Public-Library?

RC: The library was where we would meet and an important place for us as we were developing our skills. Just hanging out at the library, digging through books — it was this awesome place where it was quiet, you could concentrate, but you also had an enormous gallery of anything you wanted or any history, that’s not design-related.

We always look for inspiration in things that are not strictly in the design world. We take time off and away from the screen to spend time with family and friends – going out and exploring the world — nowadays, that is where we pull a ton of inspiration and not so much within the studio.

MR: I think one of the cool things about a library is it’s basically up to you how you use it. You can walk in and access information on anything. We want our studio to function in that way. We’ll design a building or a belt, which is what we were working on before you came in. But we’ll also do album art and logos. It’s really about how you want to work with the resource that we are and us doing that together to provide knowledge and build something. So just as people, we’re always trying to do something a little bit different. 100 different people can go into a library and get 100 different books and it’s still all in that building. We want to be that building providing those different books.

You were making projects as Public-Library while in college?

MR: No after college, I moved to New York and Ramón was here. We were just working out of a bunch of studios and agencies and got pretty burnt out quickly. I moved back and we met up one day after a crappy day of work. We were both doing our own freelance stuff — and at least for me, what I find hard when I’m working by myself is that you go in the motions and you’re just like, ‘this is how I do it.’ You don’t have that other person to challenge you or you’re not looking up and seeing other things.

So we thought, what if we just put our freelance together and see what goes from there. We basically built a completely new portfolio together, because we had day jobs and weren’t necessarily trying to pay the bills — we’re trying to be emotionally okay haha.

That gave us the opportunity to take on projects that we didn’t have to worry about the money. We could do something cool together and build a portfolio that we wanted with the types of clients we wanted. Right after we started the studio, Ramón moved to Portland.

RC: Just thinking about college, where we did have to look stuff up in books, we were halfway through college when the iPhone came out. We graduated college as print designers, but after college, this thing [iPhone] changed everything. So we had to learn web design, apps and all this shit. That was part of the rude awakening of graduating and hitting all these agencies and was like, ‘fuck this sucks. I don’t want to do this.’ I think that’s why we put our portfolios together and just thought to keep making our weird shit. Someone will see it somewhere. We just stuck with that and eventually it snowballed.

“A proof of concept of yeah, we’re making crazy shit, but we’re doing it.”

Looking back, what have been some of the milestone projects to where you are now?

RC: I was the first one to leave my job and that was huge and really scary. To make that step to have this salary and safety net, then just go for it. I think in terms of milestones within the studio: both of us leaving our jobs and slowly doing little cafe branding that doesn’t pay anything or a restaurant brand that didn’t pay much, but it was good experience, good exposure — and just seeing the way the studio started to evolve to eventually here’s a Nike project. Having that one Nike project is what I think really elevated the studio and the type of clients we can now take on. A real blue-chip client that we can actually use in our portfolio — a proof of concept of yeah, we’re making crazy shit, but we’re doing it.

I’ve seen a lot of sports related work within your portfolio. Again on your upbringing, were sports a big part and what galvanized you — from music, fashion, etc?

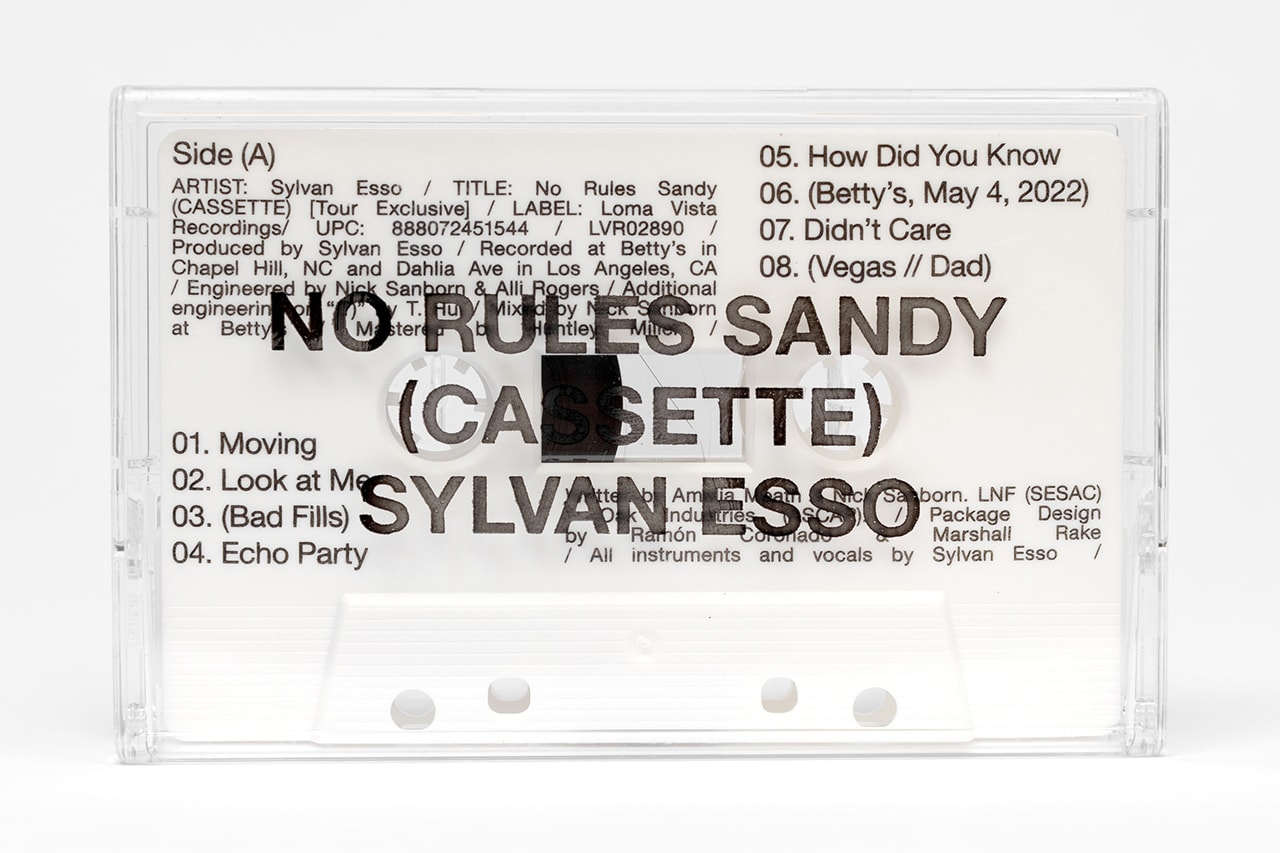

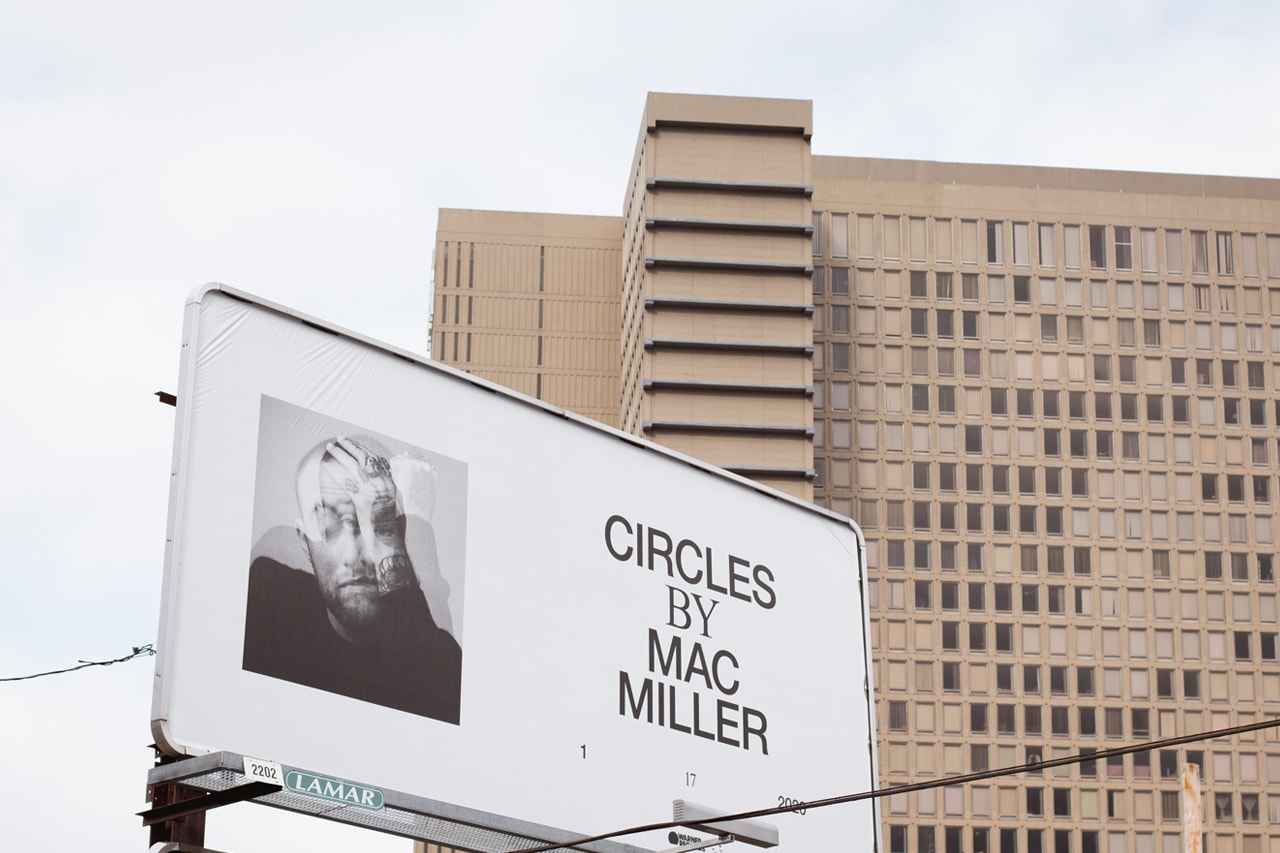

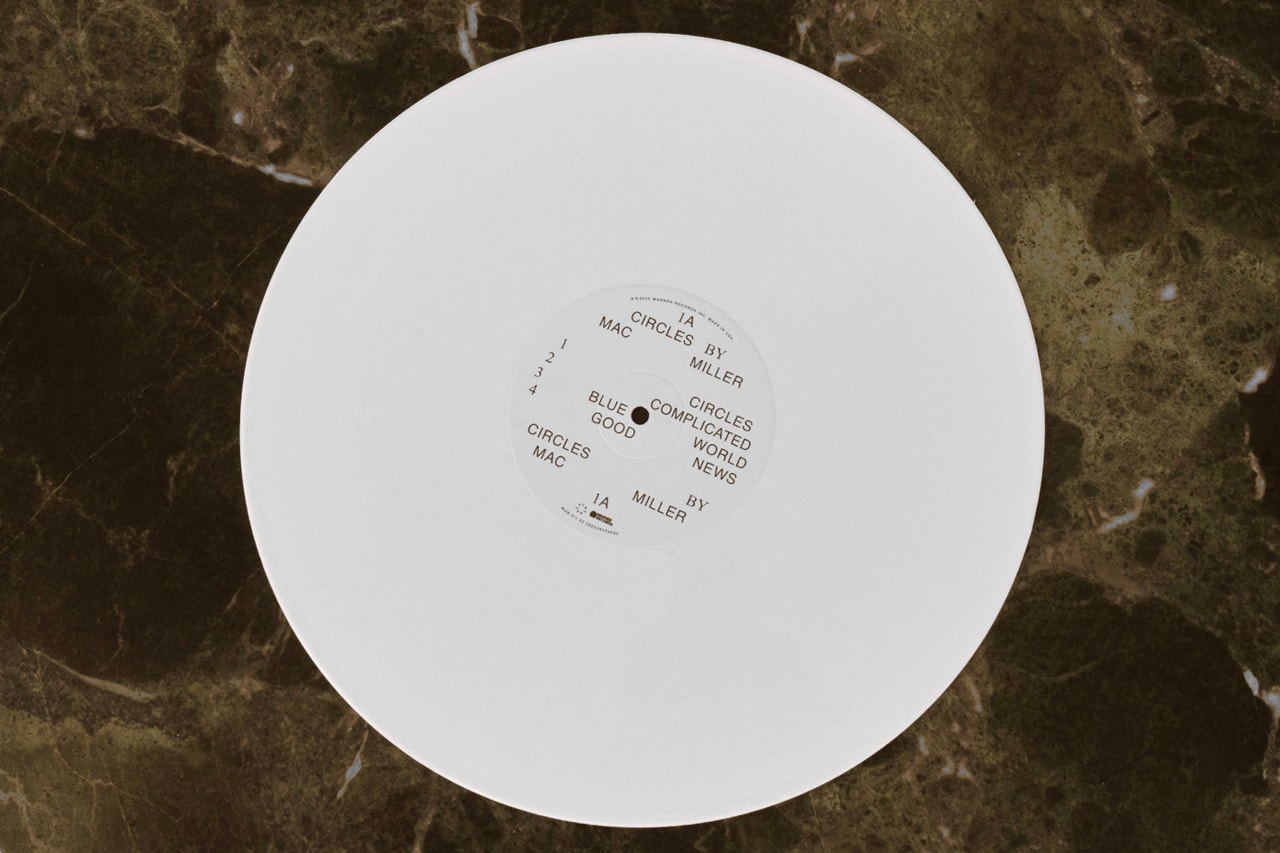

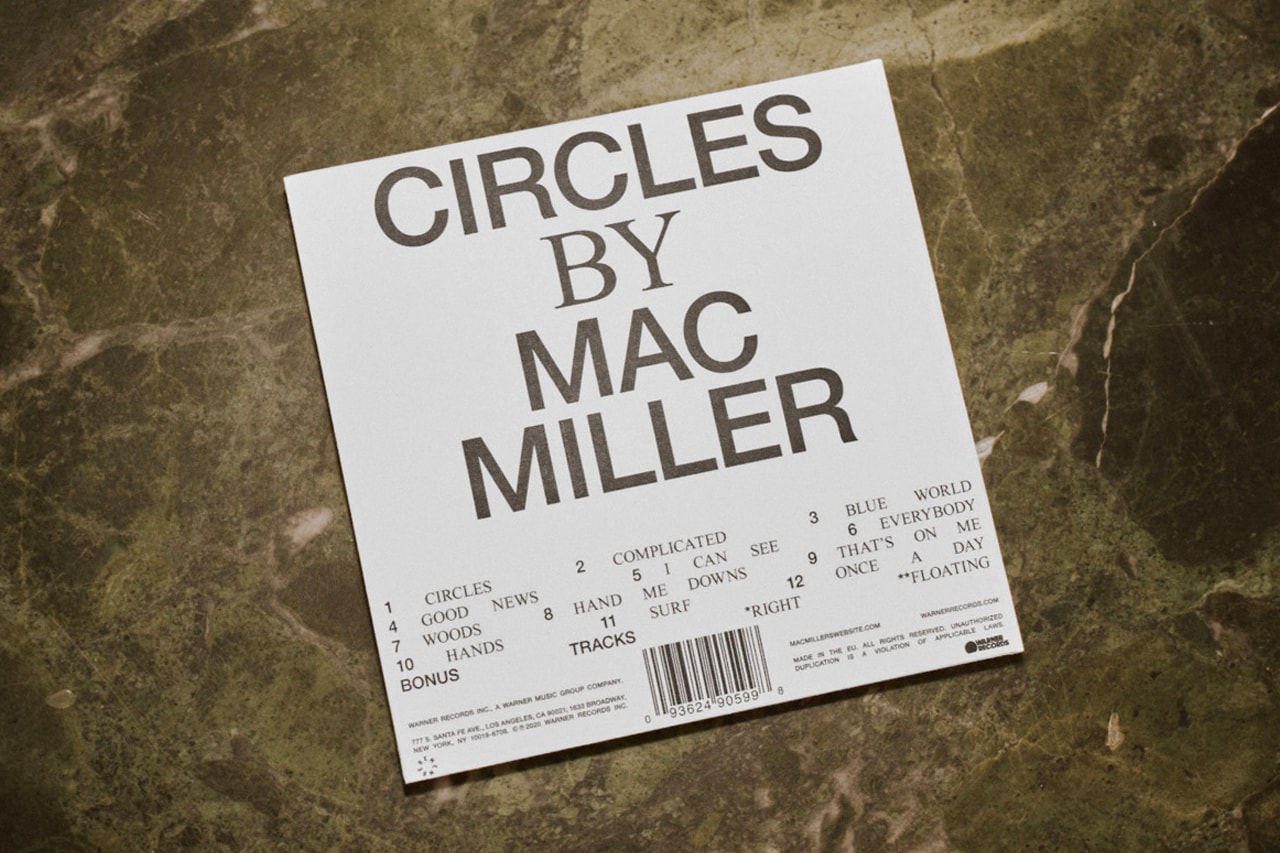

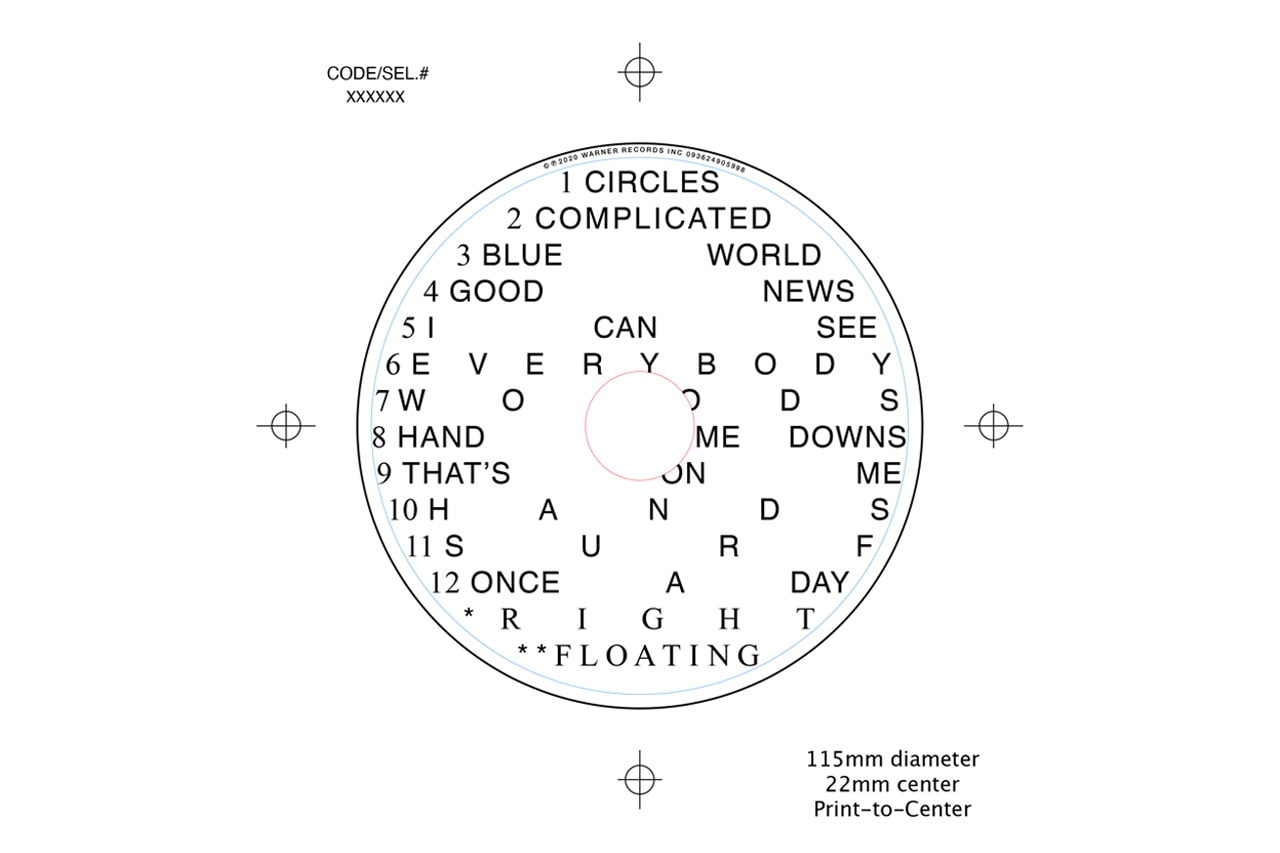

MR: Those are basically our three biggest inspirations — music, sport and fashion. We always try to gravitate towards that type of work. Music projects are really fun, because we’ve been lucky to work with artists and getting to know them on a personal level. We worked a lot with Mac Miller. For us to be in the studio and him texting us songs and making stuff to that — it’s like, what more could you want than that?

Getting these WAV files from the studio into our studio to work on the single art and he’s still recording it. Being able to have that connection with someone is really great.

The sports projects we always gravitate towards, having both played growing up. We always joke about how we meet people and all they wan’t to talk about is design and we’re like, ‘but did you watch the Clippers last night?’

Also what Ramón said before about us looking for inspiration outside, fashion is definitely a big inspiration because it’s the best example of brand building and how you can grow a brand and change your brand. If you look at any traditional fashion house, the logo is simple. They know how to breathe life into the brand through the activations they do, the way they connect with customers. They don’t put the pressure on what the Gucci tag is on the inside of their garment. The tag is beautiful, but it’s because the type is good, the material is good and attached properly. The brand is captivating because of all the other things that they do.

For us, that is such an influence in how you build something big. It’s not really putting all the pressure on the actual graphic design — how does it show up in all these other touch-points? So fashion is something we’re always looking at.

“Every single project starts black-and-white in Helvetica.”

You’re design is very minimal and pared-back. Can you describe your own practice and how you approach your projects?

RC: Typography is the foundation of the studio. Marshall studied a little bit in Sweden. I studied in Switzerland and in college, that was what we did — rudimentary typographic studies and exercises. That’s where every project starts is typography.

MR: Basically, in a foundational typography system, you start with one variable and build it up. You’re making one choice. So let’s say you’re picking a typeface, that’s one choice, then you’re picking a color, that’s another choice. You very quickly amplify your choices exponentially in a way where you’re juggling a lot of variables. So something that we do here, every single project starts black-and-white in Helvetica. By eliminating all those other choices, we right away start looking at the letters, the spacing, the content — we don’t have to think about, ‘well, if we change the typeface and it becomes more personalized, is that a true representation of the content? Or is that a representation of the style or personality that we’re trying to impose upon it rather than draw it out?’

By adding color, is that doing something or is that a crutch? We always start there, because we can get a better understanding, formally, of what we’re actually dealing with. It’s like laying all your clothes out before you pack, you need to know what you have to fit into the suitcase. We really try to break every decision down and the way that we do that is by making hundreds of designs before we simplify it down to 10 designs, just because we want to know all the corners of the world that we’re trying to develop and understand all the possible decisions and implications of those decisions.

Apart from the Mac Miller cover, what are some other projects over the years that have been the most fulfilling?

MR: Before the Olympics, we worked with Michael Norman, the 400 meter sprinter. He’s incredible and some of these Nike projects, when you get to see the athlete perform — watching the best 400 meter runner in the world even lightly run on the track and understanding that both him and us are human beings is crazy.

I think anytime you work with an athlete or an artist that is that other one-percent different than you is really energizing. You have a chance to help them tell their story, which is super cool and you feel a responsibility to do that well.

RC: The Grammys to me was a fun project, because it felt for the first time, we had very different eyeballs on our work. CBS, mainstream TV, normal people that watch the Grammys, as opposed to the cultural work for Nike, etc. So that was interesting and a fun challenge to design something that the masses will have their eyeballs on basic cable. Marshall and I were in here everyday just redrawing that gramaphone a million times playing with type, shape and trying to build this world.

Has that been the most challenging project thus far?

MR: I think what’s cool about doing something that big is obviously everyone else that has done it before you — it’s very public. You can see an example of what last year looked like and what it looked like two years ago. You don’t always have that for a given project. For the Grammys, it’s like, here are 40 previous iterations and trying to develop that with all these different types of artists and audiences — while trying to bring our perspective to it.

The team here is three people, so we’re doing a project that is usually done by 100 people. And that’s just how we like to do it because we hate ourselves haha. Like Ramón said, that project had a lot of challenges, but it was very cool because that’s something that even my grandma would get to see.

“Take the risks, do all those things that you aren’t sure of — keep pushing that feeling.”

The studio is such a think-space where you can go any and all directions. What are some mediums or projects that you haven’t touched yet that you want to work on?

MR: A big thing lately has been product, like a bag that we’ve been working on from start-to-finish. We did a collaborative t-shirt with Actual Source earlier in the year — they’re buddies of ours and we’ve always wanted to do something. We did a beach towel with Basic.Space. We’re also working on sunglasses with AKILA.

RC: I think it goes back to the idea you were talking about with the artist-designer. That’s something we strive for in the studio is to always have a project that is coming from us — whether a beach towel, sunglasses or maybe just a poster series. Back in 2015, we would just take the day to design posters that are self-initiated by us — whether it was on the NBA Finals, World Cup, Champions League — just to get our our ideas and things we wanted to try with that content, because we didn’t have that type of project, so it would just be a time for us to study.

Designers are traditionally just providing a solution to a question, whereas, the artist has this question and puts it out into the world. Those self-initiated posters fall in line with that same approach. You’re putting this question out for your own fulfillment and exploration.

If you were to look back 10 years and give yourself advice, what would you say?

MR: Great question. Ramón said in the beginning that we always took an outsider approach on things — where eight people did it one way, where we did it another. We still get asked to do things we’ve never done before. We’ve been working with Nike for like 10 years and one of our first biggest projects with them was doing these buildings on their campus. Not just the wayfinding, but specking the furniture, designing pieces that would go in there — it was very terrifying — but we had that same approach of, ‘if we’re going to do it? Let’s do it in a way that no one else would.’

I think reinforcing that it’s ok, take the risks, do all those things that you aren’t sure of — keep pushing that feeling, which is the part of the work that people react to — those chances and trying something different.

RC: Also knowing when to walk away from a project was a big lesson too. We’ve had to basically walk away on a couple of projects where it didn’t feel right. We tried to make it work and knowing that’s fine. Not every relationship has to be great and we don’t have to come up with a great product from it — sometimes it doesn’t work out and it’s ok to walk away from it.

Photography by Shawn Ghassemitari and Public-Library.