Creation and destruction are central to Urs Fischer. For three decades, the Swiss conceptual artist has shifted our understanding of reality through collage-like photographs and paintings, as well as large-scale sculptures and installations that explore themes of perception, absence, and representation.

Born in Zurich, but now based in Los Angeles, one could call Fischer a miner of images and material, where disparate objects (literally) collide with one another, much like the thoughts that endlessly race through our minds. Examples of this can be seen in his anthropomorphic sculpture, Bad Timing, Lamb Chop! (2004-05), where he depicted a massive cigarette box and wooden chair fused together in cast aluminum, polyurethane resin, and finished with enamel paint. Both objects, despite serving completely different functions, are by humans for humans. Under the sculpture, however, the human is a tiny afterthought who marvels at the sheer scale of their once subservient tools.

This overlapping of ideas continued on in a 2013 duo exhibition at MOCA’s Grand Avenue and Geffen Contemporary locations in LA, such as in Portrait of A Single Raindrop (2013), where it appeared as if a giant monster had rummaged through the walls of the gallery — revealing a labyrinth of clay sculptures. Made with the help of 1,500 people in LA, it’s hard to discern where each artwork begins and ends — giving way to one unified piece, where notions of authorship come into question, as does the blurring between the artist, viewer, studio, and gallery.

“Anything you find in a different context, that’s not your own, you will think about it. It’s a story.”

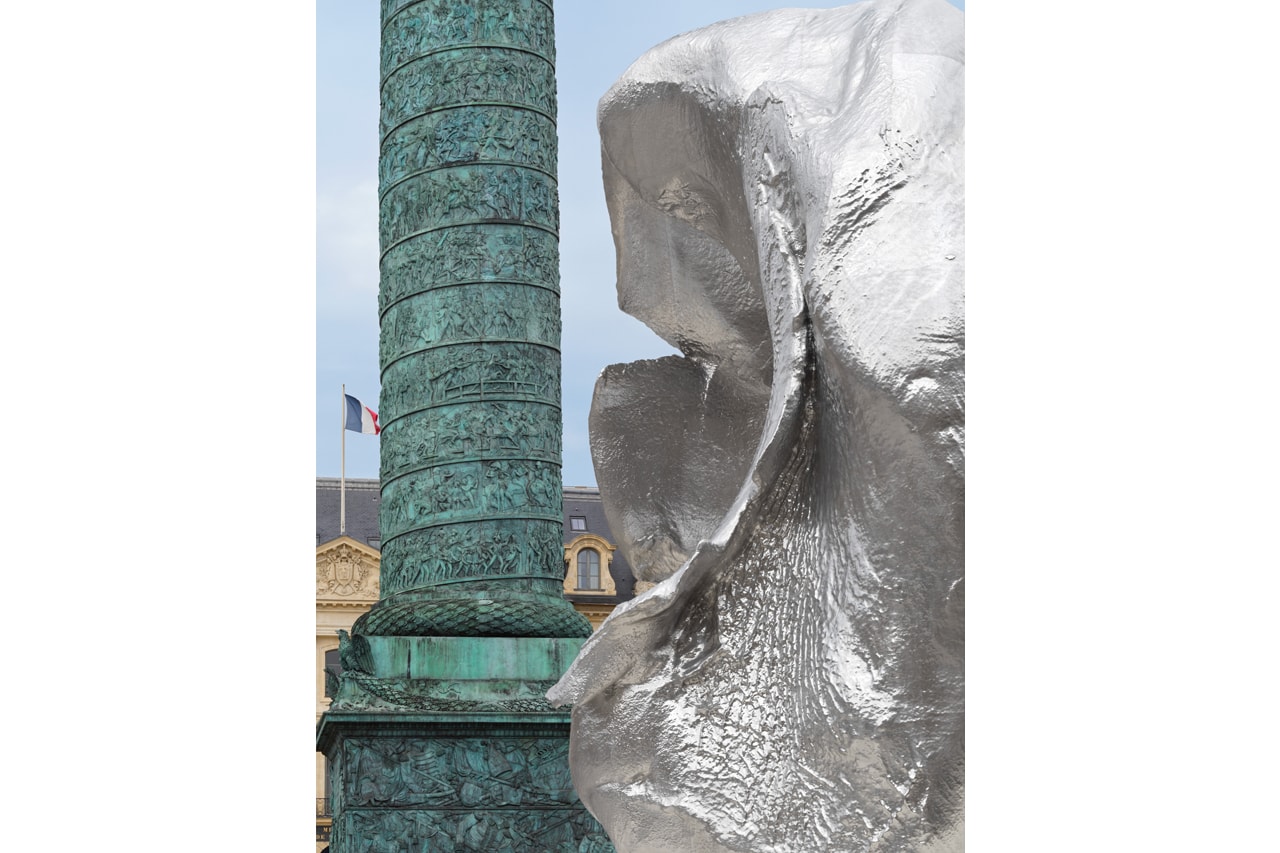

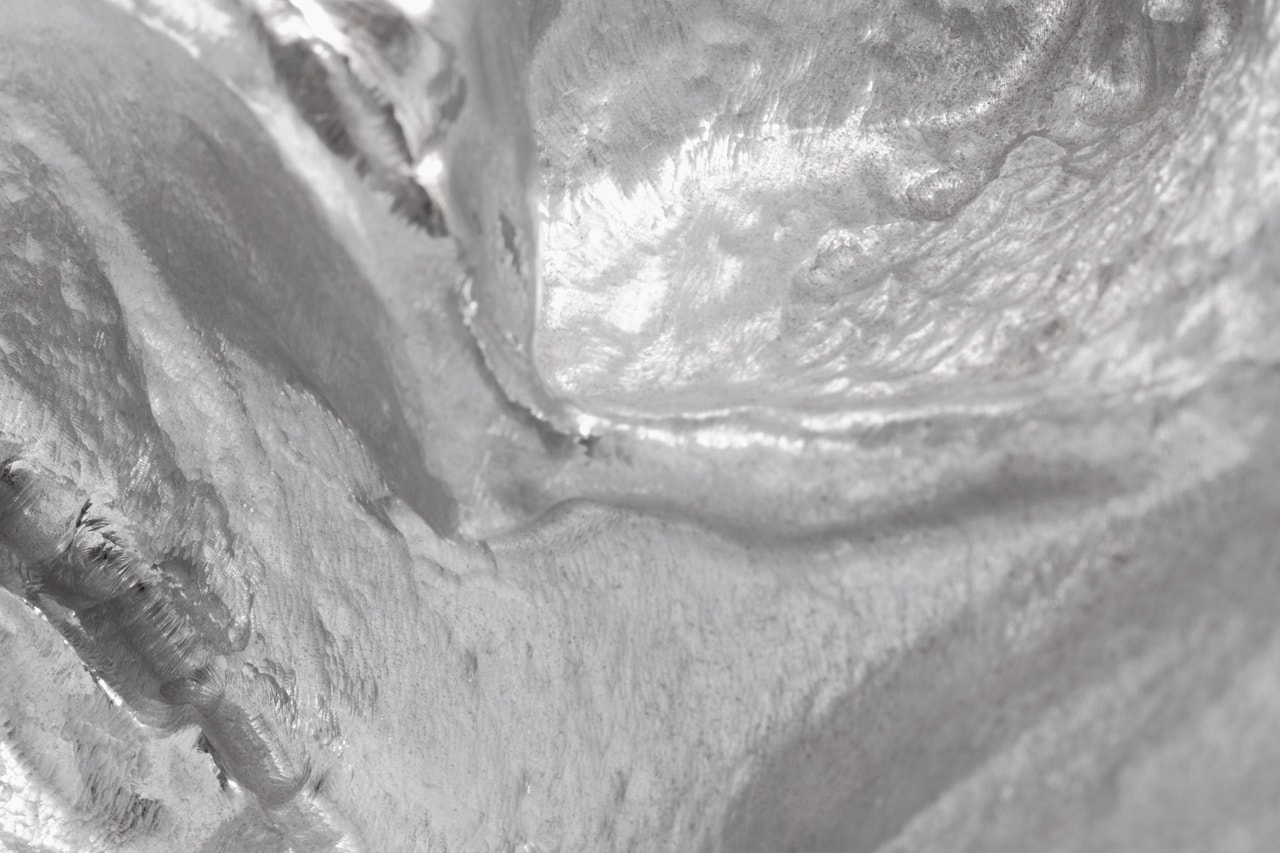

When asked by Hypeart on how he would define his nebulous practice, Fischer explains that he is just trying to use every part of his body. “I’ve pretty much just given myself permission to pursue whatever comes to my mind,” he adds. This week, that enigmatic thought process resulted in a massive aluminum Wave — the sixth sculpture in his Big Clays series — which is currently on view in the center of the Place Vendôme in Paris until November 30. Coinciding with the upcoming Paris+ par Art Basel fair, launching tomorrow until October 22, the sculpture originated as a small mound of clay, which he gripped, kneaded and squeezed instinctively to shape. In a statement, Fischer described the process as “a sensual and repetitive gesture, like a bodily motion,” which was then 3D-scanned, digitally reconfigured, and cast into a 17-foot colossus now towering over the viewer.

At odds with the Haussman-style architecture that surrounds it, Wave appears like a prehistoric object — perhaps the weight of mother nature itself — freeze-framed to poke holes at the traditions of humankind. His latest sculpture wasn’t the first time he took the French capital by storm, either. Several years ago, Fischer was the first artist to inaugurate the Tadao Ando-designed rotunda at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection.

Orbiting the center were a series of wax sculptures — one of his friend, fellow artist Rudolf Stingel — who was depicted in contemplation around wax chairs sourced from different cultures around the world. In the middle of the rotunda stood the centerpiece of the show: a giant candle replica of Giambologna’s The Abduction of the Sabine Women (1579-82). Initially resembling a mastery in realism and beauty, each of the sculptures melted to the ground during the show’s eight month period as a commentary on impermanence, metamorphosis, and the passage of time. While again, Fischer demonstrates a keen willingness to destroy what he creates, the very space in which he exhibits his work is of equal importance.

Much of his recent studies have resided in the boundless frontier of digital art, most notable in his CHAOS series of NFTs. Like Bad Timing, Lamb Chop! (2004-05) and similarly Frankenstein-like concoctions, such as Horse/Bed (2013), each animated artwork is like a thought-exercise where he laboriously recreates real objects in space. At times humorous, dizzying, and undeniably thought-provoking, everything from three-dimensional renderings of houses, eye charts, and fire hydrants float through one another in a jig-saw puzzle for the viewer to piece together. In Sleeptalker (2023), which depicts a sheet of film hovering through a purple vase, Fischer tells Hypeart that the inspiration came from a random film roll he bought on Etsy. “Say you find a photograph on the side of the street, you look at it and it becomes interesting,” he explains. “Anything you find in a different context, that’s not your own, you will think about it. It’s a story.”

Everything has a story, from a ceramic vase perched on a table to items discarded in the trash. On our call, Fischer talks about a pair of sneakers that he bought just prior to our interview. “The amount of civilization that’s in these sneakers is crazy — from footwear to marketing to distribution to the plastics developed and how to fuse and package them,” the artist stated. “In everything you see, there’s a ginormous amount of history. In some ways, this exploration [CHAOS] was also a way to treat everything equally — a piece of crumpled paper is the same as a diamond.”

Fischer is quick to note that he doesn’t really think NFT’s were made to be an artwork. Nor does he see the immersion promised through the metaverse as quite there yet. With that being said, he still finds it all too strange to observe how absorbed people have become into their phones. “You still go to the venue, but everyone looks at their screen to see the performance and almost understand things better when viewed on a screen, because a camera does some kind of editing for you.”

“Advertisements have [now] defined the collective language globally at this point”

Where, say 10 years ago it was a little disdained, it has become almost strange for someone to not record a big moment on their phones while at a concert, sporting event, or at dinner. Apart from the perplexing CHAOS animations he posts, Fischer is not really interested in using social media — at least not to promote his own likeness. But he is inquisitive about the phenomena surrounding it, leading to his Denominator (2020-22) digital sculpture, unveiled at Gagosian’s Beverly Hills location last year. At the center of the exhibition stood a 12-foot cube displaying thousands of fragmented snippets sourced from the history of advertisements.

Unlike giant monuments in antiquity, marble sculptures in the Renaissance or paintings and films up until the first half of the 20th century, “advertisements have [now] defined the collective language globally at this point — of what things are and what desires look like,” Fischer remarked. “In some ways, they [ads] are some of the strongest visual contributions in centuries. They create our inner image, a world order in our brains.”

While the ad industry is filled with “genius” forecasters and creative directors, Fischer states that this “experiment on humanity” is largely without a plan. Content has replaced culture, and we just “move in that culture. We don’t know how that culture affects us or what it does to our lives and experiences,” he adds. Denominator (2020-22) was conceived under this premise, to create an encyclopedia telling the story of humanity through the source material that recurrently informs our present.

By training ChatGPT to generate its own questions off simple prompts, such as commercials from “all over the world since the onset of TV ads in the ‘50s,” Fischer uncovered commonalities within society over the past 70 years. “It could be a shoe, but it could also be a countryside family gathering or Baroque fashion that describe products marketed to 12 year old girls. You find images that describe these situations.” Like his oeuvre, Fischer doesn’t charge his art with any of his own socio-political beliefs, but leaves that to the viewer to assemble meaning for themselves.

For a conceptual artist, concept has never shown to be the primary concern for Fischer. Instead, like a child in a sandbox molding castles and kingdoms, he plays with time and space as a material to realign our perceptions of reality. When asked what the greatest piece of advice he had gotten during his formative years, Fischer recalls arguing with a professor, who told him: “There is always a door.” Referring to the door to exit the classroom. It’s not clear whether he stayed or not, but when the question then flipped on him, Fischer reflected, “Listen, but don’t listen.”

All photos courtesy of the artist and Gagosian.