D*Face Reflects on His First Collaboration With Banksy

Plus his take on how the British street art scene is evolving.

You are reading your free article for this month.

Members-only

It was an early love of skateboarding that saw British street artist D*Face first find the inspiration to create the initial sketches and characters that established him as one of street art’s most prominent figures. Starting by producing stickers while working in a nine-to-five office job, the London-based creative has since collaborated with contemporaries such as Shepard Fairey and Banksy, and produced album artwork for the likes of Lady Gaga and Blink-182 with a style that’s become instantly recognizable both in London and overseas (click here to see the Los Angeles mural he completed earlier this year). He also had a major part to play in the legitimization of the art form through the launch of London’s Outsider Institute — the city’s first contemporary gallery focused on street and urban art — which he launched in support of a burgeoning local street art scene.

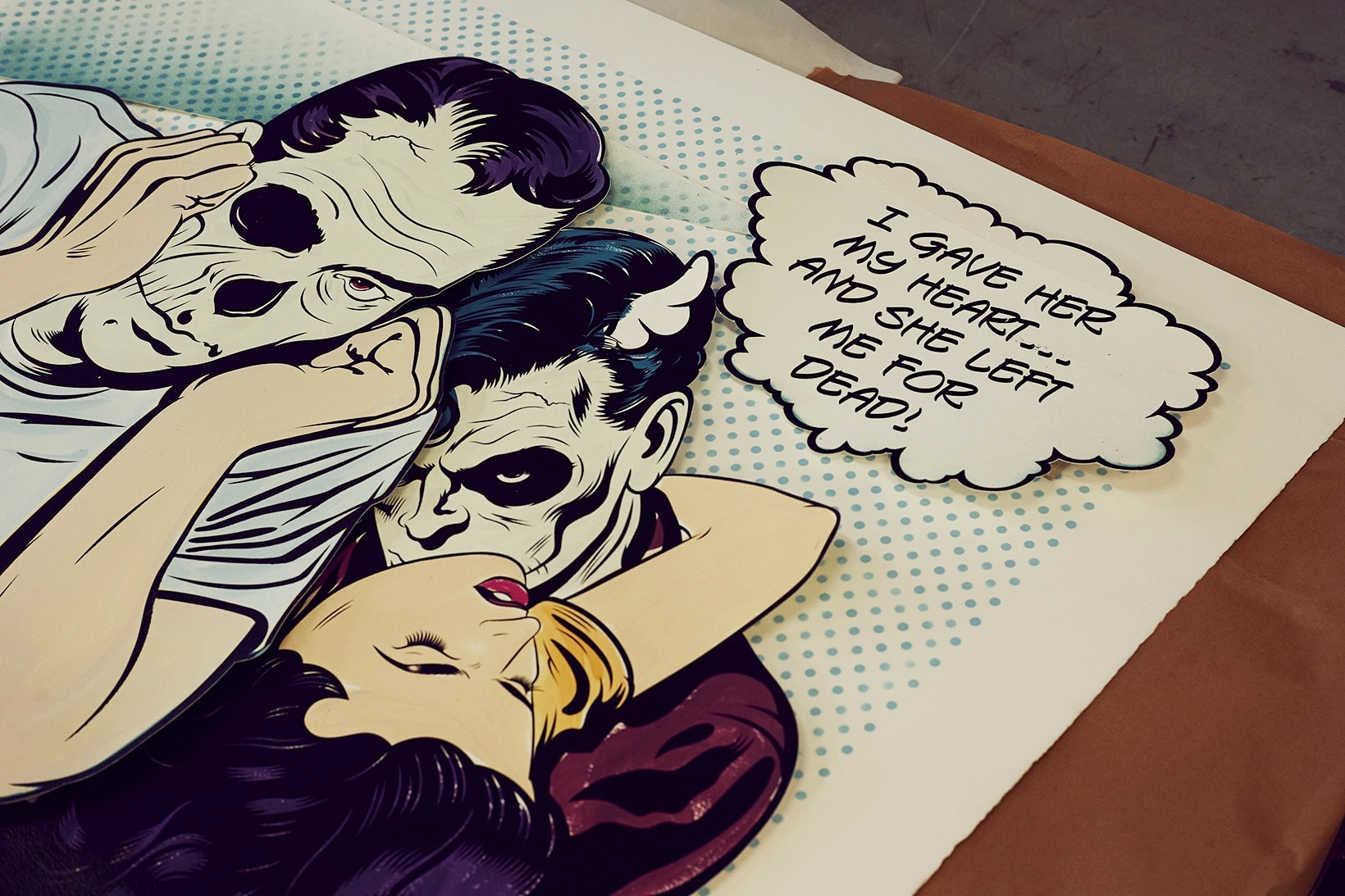

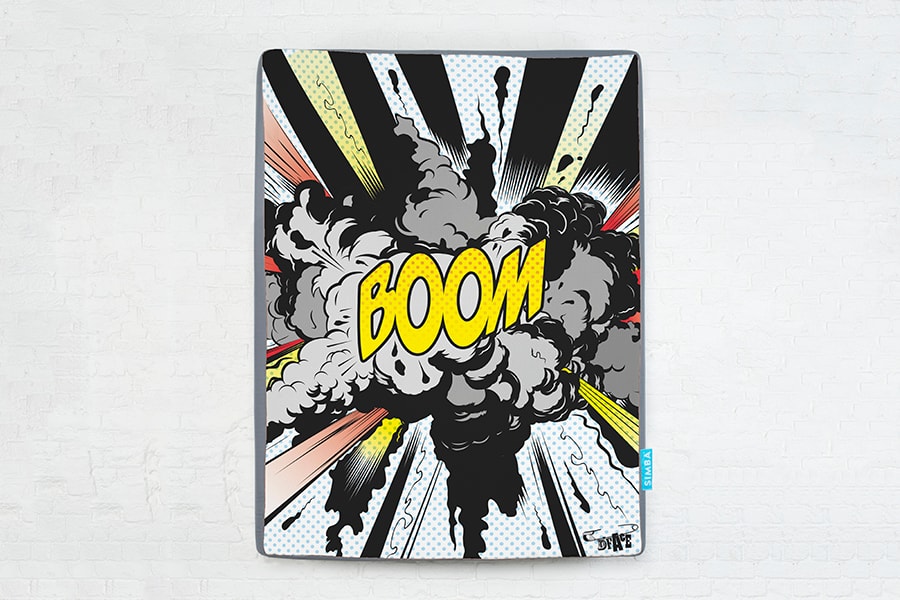

Having produced groundbreaking work on everything from banknotes to billboards, D*Face’s most recent commission is for innovative mattress firm Simba where, alongside several other pioneering artists, he was asked to produce an art piece using a mattress as his canvas, with the results sold in support of homeless charity Crisis. During a break from his various projects, we caught up with the artist in his workspace to find out how street art was first elevated from illegal protest movement to revered art form and the effect on the scene it first originated from.

How did you first get into street art?

The things I was inspired by as a teen were never what was in galleries but instead the skate graphics, the album art and T-shirt graphics that I was fed back then. I wasn’t very good at school but I was always drawing and doodling and around that time I got into skateboarding. My parents finally bought me a board and it started my fascination with skateboard culture. The older kids would pass around copies of Thrasher magazine, which was amazing visual candy full of Californian culture, graphic art, punk bands and other cool shit.

I got onto an animation course and I started along some sort of career path in graphic design. I began drawing characters on a layout pad while I was waiting for files to save and a colleague convinced me that I should do something with them. I started drawing them with a marker pen onto sticky-back plastic and making stickers and rather than getting the bus home I’d walk home and stick them up along the way.

How did meeting Shephard Fairey change your life?

I connected with Shephard Fairey in 1998 or 1999 as he was one of the first to use screen printing techniques to mass produce stickers. I emailed him early on when he was new on the scene to tell him that I liked what he was doing. He responded and sent me some stickers and I said I’d put them up when I put my stuff up. He came to London for a poster show in 1999 and asked if I had a car, bucket, paste, and a ladder to help him out. Meeting him in London with this very dialed technique showed just what I could do, going from stickers to illegal billboard posters. He showed me a direction that I could apply to my work and started a relationship that I still have to this day.

What was happening in London at the time?

There were a few people in London doing something similar: the Toasters, Solo-One, Boyd, The London Police and Banksy, who had moved here from Bristol and hit it hard using stencils. But stencils were just one techniques being used; it’s like a toolbox — you’ve got stickers as standard, then stencils, big posters, billboards and freestyle pieces. In inner London it wasn’t about painting trains and tracksides like elsewhere, but it was about getting into the heart of the city, among the riffraff.

How did your work evolve?

In about 2003 to 2004 I started printing on banknotes and spending it so people would get it in their change, which started to become something resembling pop art. This caught the attention of Banksy who at this point had become a bit of a household name despite still lurking in the shadows. He emailed asking to do a collaboration and from that came prints. He was one of the first to realize that trying to sell canvases at £500 GBP was really hard compared to selling 10 prints at £50 GBP each. After selling out of these prints, I realized that there was a scene emerging and that maybe it had started to capture the public’s attention.

The streets are there and they’re yours, so go and take them

How has the scene changed?

I hated the phrase “street art” when I first heard it in the early 200os, as it sounded like it was a marketing term. But it did mark a step away from the days of graffiti and the scene quickly evolved to the extent where there were categories within it, including mural artists — who had often never done anything illegal — or those whose work is found in galleries, which had obviously not come from the street, so “urban art” became the new way to define it. Whatever you call it, it has become embedded into popular culture, which also means it has become less effective and the impact of, say, putting out a new sticker has been lost. It’s like anything that becomes injected into the mainstream culture — there are pros and cons. The key thing is to stay true to what you believe in and retain your integrity.

How did the mattress commission for Simba come about?

I get a lot of emails from brands asking for help on different projects and every now and again one sticks out and I liked the possibilities of this project — it made me think creatively. I’m doing an installation for the exhibition and I gave it my own twist. Magic things happen in bed so that connects to both the installation and my tongue-in-cheek vision of the brief.

Is the London street art scene a supportive one?

There are a few of us who are good friends but the London scene is very “London” and it’s not always very supportive. Everyone wants you to do well when you’re an underdog but once you’re not an underdog they can try to find your flaws and that can be quite disheartening. But worldwide it’s a supportive scene and I can travel to any city and be welcomed by a bunch of people doing their own version of street art and that’s thanks to social media and the internet.

But the interest is here – you can see that in the street art tours, which gives you a gauge on how the public are enthused by it and it hasn’t dropped off, and I don’t want to hate on London. I think in London it’s still not considered highbrow and we’re a little bit behind in that outlook and mentality but we’re amazing creatively.

How have art galleries reacted?

The galleries exhibiting street art now have often grown from the ground up by people embedded in the scene. This was probably the first art “moment” to use the internet to frame itself. In 2008 it was nuts — street art was at its most hyped peak in terms of sales. I remember thinking that it can’t maintain it and it’s just a trend or a fad but the way in which its grown is really organic and not reliant on a gallery.

What makes street art such an important art form?

It talks to the public in a voice they understand and it uses imagery and forms of graphic communication that they’re very attuned to. It doesn’t talk to people in a way that is exclusive or that makes you feel you need to be educated to understand. Street art can be really empowering and there‘s nothing stopping you doing it apart from you — the streets are there and they’re yours so go and take them. If you’re critical of what’s out there and think you can do better than go and do it as there’s no curator there telling what you can and can’t do.