You Can't Eat Cool - Or Can You?: A Conversation Between Reasonable People

I thought it would be interesting to speak with my friends about how streetwear and contemporary

I thought it would be interesting to speak with my friends about how streetwear and contemporary fashion have been affected by major league, big-time shit that’s happened in the world over the past few years. I chose Chris, Yosef and Stu for the feature because when I need to know why 35 dollar socks are now a thing (do I buy?), or how to manage my plummeting investments (do I sell?), I often go to them for advice on both.

Phil: Please introduce yourselves – names, what you do.

Yosef: I’m Yosef Johnson, I’m an account executive on Jordan Brand at Wieden + Kennedy New York. Before that, I was an analyst at JP Morgan working with private equity and financial sponsors.

Chris: I’m Chris Paik, I work at a small venture capital firm here in New York. We invest in early-stage, mostly consumer-facing tech companies.

Stu: My name is Stuart Leung, I’m currently a Wharton Business School student interning in the city at a credit fund. After I graduated from college in ‘05, I worked at Lehman Brothers doing leveraged finance and investment banking. Then I did two years of work at a private equity firm called Sun Capital Partners, and then I helped manage Rocksmith as CFO.

Phil: First and foremost, I asked you guys to do this interview because I know that each of you, to varying extents, were influenced by streetwear and sneaker culture growing up. Can you guys speak a bit about that?

Chris: I grew up outside of San Francisco in the suburbs. When I was in high school, the first shoe I really fell in love with was the Jordan 11 when they retro’d it in 2001, I think? Then I just spiraled out of control like most people tend to do. I would try to buy two pairs to cover the cost of one pair… sneaker arbitrage, if you will, to fuel my habit. Continued through college where my taste changed a little… I started moving towards where Highsnob and HYPEBEAST are going now. The gateway drug was definitely raw denim.

Yosef: I grew up in Chicago, so Jordans were everything… and then from there you kind of moved through every other type of Nike. Also, I went to Williams College, and if you hit people with a pair of sneakers up there, they’d be like “what? what are those on your feet?” so you could be the man with like four different pairs of whatever.

Phil: I’m pretty sure Stu never did, but Yosef and Chris, did you guys ever line up and/or camp out?

Chris: I did a couple of times. The first time I stayed overnight somewhere was for the Stash drop at NORT/Recon in San Francisco.

Phil: What did your parents think about that?

Chris: They were supportive. They brought me food.

Phil: Was it just you?

Chris: Yeah. You know. They rolled up in the Previa. Dropped off some food.

Yosef: The only time I waited outside was with the intention to flip. It was outside at Niketown in Chicago and it was when they dropped the N.E.R.D. Dunks and the Espos, I think.

Phil: So you were actually flipping, too?

Yosef: Yeah, a bit, not a ton. I always liked to wear what I bought, and many times I just didn’t even have the money to get the second pair anyways.

Phil: So at the W+K NY office, you’re one of the guys who is the most indicative of where contemporary menswear is at… when did your style shift from what you were wearing in high school and college to what you are into now?

Yosef: I think it’s when I moved to the city after college. I went to go work on Wall Street, so it’s like, you know the sneakers are gonna get thrown on the shelf. That said, I still loved fashion, so when I moved into the finance world, I was really into finding out what the cool shit that works in that scene was.

Phil: What about you, Stu?

Stu: Well this isn’t exactly answering that question, but to correct you on an earlier point, I actually did line up once for shoes. It was when the Jordan 11s FIRST came out back in 1996, and I went with my mom. I was on the game early all the time because I have older sisters who bought me every Jordan that came out. I had the Chris Webbers when they came out, Pippens in two colorways, I was hooked up! So when the 11s came out, everyone was talking about those, and my mom took me to get them.

Phil: By the time I got to Dartmouth, though, you were a senior and definitely out of that phase though, right?

Stu: Yeah. Like Yosef was saying, moving back to the city for work did that. When you first met me, I had already spent 9 months interning in New York.

Phil: OK so now that we’ve covered your personal stories, let’s discuss how you guys feel about the current landscape and condition streetwear and contemporary fashion finds itself in. Economically, stylistically, culturally, so on and so forth.

Chris: I think one of the most interesting shifts in fashion is certainly the emergence of e-commerce. A good case study of how this works in the streetwear world is Karmaloop, and specifically, The Kazbah. Karmaloop doesn’t hold any inventory for items represented in The Kazbah, but as an independent designer you can borrow their distribution and sell through the Karmaloop name. This is different from something like Digital Gravel, which held all of its inventory. Outside of streetwear, you have all these things like Shopbob, Net-a-porter and Yoox, which are all very interesting innovations in the sense that designers and aspiring fashion entrepreneurs can sell and scale their businesses faster than they ever could by selling t-shirts out of the trunk of their car.

Phil: The Digital Gravel vs. Karmaloop point is an interesting one. I remember Digital Gravel was the first online store for streetwear in a lot of ways. What happened? You see a lot of online streetwear retailers losing steam, and yet Karmaloop stays so far ahead of the pack financially.

Chris: It comes down to inventory risk. When you hold inventory you have to purchase wares wholesale from designers. So, by virtue of it physically taking up storage space you have to pay for, if you can’t move and offload it, you’re taking a financial hit. Simple. So you have to think about operations, warehouses, shipping…

Phil: But Karmaloop does hold inventory, too.

Chris: Yeah they do. I don’t know what their numbers look like exactly, but I would say that the vast majority of their revenue comes from the cut that they take from supporting the Kazbah brands.

Stu: So, I’ve been on the other end of interacting with Karmaloop while I was at Rocksmith, as we sold to them. Because of their scale – they’re a huge buyer – they receive a discount, and it’s kind of mandatory when you start selling to them.

Phil: Is that common practice with most retailers?

Stu: It depends on the order sizes. If you have larger guys with more doors, you’re going to give them discounts because there’s more volume, so it induces them to order more. Karmaloop gets good pricing from all of their vendors, and I think the diversity of product and their brand portfolio is what really makes them successful. There’s risk involved in that because, yes, they’re holding a lot of inventory, but they’re pretty good at forecasting and inventory management. It’s a pretty good model.

Phil: A lot of online retailers in the streetwear circuit were initially run by people who all had a very similar brand portfolio and M.O. as Karmaloop. How and when did Karmaloop leap so far forward in terms of market share?

Chris: I think, all marketplaces, whether it be online streetwear or fashion e-tailing, are subject to power law distribution. This means that 20% of the players control like 80% of the revenue and traffic. The thing is, the early retailers had first mover advantage, certainly, but you’re only as competitive as your rate of innovation. The Kazbah is the purest form of how Karmaloop leveraged the network effect for both their audience and designer network. With each additional person visiting the site, it’s more incentive for brands to sell through Karmaloop, and vice versa. Being able to scale the sellers on Karmaloop without taking on additional inventory risk is such a smart thing. Also, if a brand does well in the Kazbah, it’s a really safe way for Karmaloop to crowdsource who they should bring in to their full retail lineup.

Stu: Karmaloop is the Amazon of streetwear. If you want anything in streetwear, you go to Karmaloop. You don’t have to look anywhere else and the pricing is good across the board. It’s a one stop shop.

Yosef: There’s a lot to be said about the diversity of product offered at Karmaloop. I think a lot of other streetwear retailers focused really heavily on one specific look or style, so they kind of ended up in the water when trends shifted elsewhere. If you’re not invested in a breadth of options, you’ll always end up being stuck with the one thing.

Phil: OK moving onto a specific thing that I wanted to talk to you guys about…thoughts about I.T.’s acquistion of A Bathing Ape?

Yosef: Who didn’t see that coming? A Bathing Ape’s design aesthetic is so specific, and the appeal throughout the brand’s history was that it was expensive and hard to find. The second they opened a shop in New York and you saw every dude in hip hop wearing it, it lost all of its cache because it became too easily accessible.

Chris: How much did I.T. buy it for again?

Phil: 90% of the company for 2.8 million USD.

Stu: …WHAT?

Phil: Can you talk about what that means? Everyone read that article, and because the figure was so low, folks had a vague understanding that it was a crazy deal – but when you guys hear that it obviously sets off different red flags.

Chris: Selling 90% of a company for 2.8 million USD basically means the TOTAL ASSETS of said company were valued at just north of 3 million USD. That’s not a lot. What probably led A Bathing Ape to sell for as little as it did is that brick and mortar locations are incredibly expensive. If you have a company that relies on restricted distribution to stay exclusive, it doesn’t make business sense to have half a dozen, or more, stores. There’s always a fine, paradoxical line between trying to balance how exclusive a brand is and growing revenue…making money. Period.

Stu: That’s something we had to consider all the time while I was at Rocksmith. You have two options: you can stay exclusive and keep your retailer list super limited, or you can grow the business and move into chain retailers. It depends on what your goal is. If you want to maintain your status as a cool, small brand, you’re not going to make a lot of money and it’s going to take you a while longer to get profitable. BAPE is distinct because their margins were so ridiculous. It’s the same quality of t-shirt being sold for 70 bucks more than a Rocksmith shirt. I guarantee Nigo’s t-shirts cost 7 bucks a pop, tops.

Yosef: I think an interesting thing to talk about might be Supreme’s numbers. They seem to have found that sweet spot better than anyone else.

Phil: That’s a good point. The larger question here is: is it possible, within the streetwear space, to have a brand that maintains that cultural cache and gravity alongside being a profitable business?

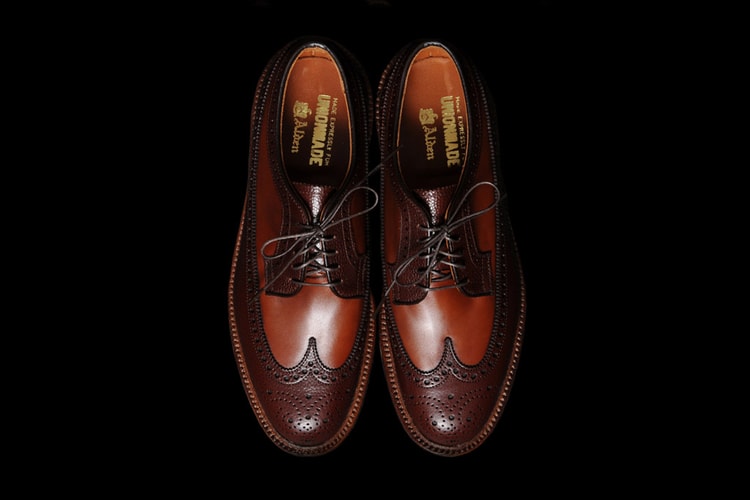

Chris: I think… whether it be a streetwear brand or a footwear brand… what has the best chance of becoming big while also feeling exclusive are things that are well designed. Common Projects is a good example. They maintain an air of exclusivity because they’re expensive. They go for anything between 300 to 500 USD… which is more than most pink box SB’s on eBay. But more importantly, they’re just beautiful shoes.

Yosef: When Common Projects hit, they hit right when everyone was jumping on the loud bandwagon. They came in and presented a super crisp, slick option for everyone who was tired of seeing these neon colors everywhere. So it’s a combination of beautifully executed design and how they filled a void in the market. They’re not unlike Supreme in that way. Supreme has done a great job of creating a mystique around its brand. The harder to obtain something, the more appeal it has in this culture. With Common Projects it’s a price point thing, and with Supreme it’s the really exclusive, controlled distribution of its product.

Phil: So do you think the exclusivity-for-exclusivity’s sake thing still works?

Chris: Yeah. Though, brands are increasingly relying on price to make them more exclusive. Look at 3sixteen. They started as a strictly streetwear brand, but now they’ve very successfully transitioned into contemporary menswear.

Phil: Speaking of exclusivity, another phenomenon I wanted to address is The Hundreds and Johnny Cupcakes. They kind of sit on the opposite end of the spectrum for me, in that their operations seem to entirely be about being inclusive. Can you talk about why you think The Hundreds and Johnny Cupcakes have done so well for themselves?

Chris: What those two brands did well is that they recognized they were first movers in this new/current wave of streetwear. They came in at the right time, when streetwear was still a little foreign to the mass market, and did a good job of making streetwear accessible and affordable to kids who couldn’t afford the $90 t-shirt while making them feel like they were still part of a tight club. It’s all in the execution.

Phil: Like the first Johnny Cupcakes shop, which opened in Boston around the time you were at Harvard, right?

Chris: Exactly. The whole thing was that you would walk inside the Johnny Cupcakes store, and the experience was such that people who didn’t know would be confused because they’d think they were in an actual cupcake shop.

Stu: Well let’s go back to the original question. I feel like lots, if not all, brands in streetwear, at least attempted to follow the model you’re describing, Chris. So the question is why are these particular brands we’re talking about so much more successful than others?

Chris: I think The Hundreds’ blog plays a big factor in explaining that. Psychologically, if something’s more accessible and familiar, people are more prone to favor it. There was a study that found that the more you see someone, the more attracted you are to them.

Phil: Well to me, The Hundreds is almost the opposite of Supreme. Supreme built its mystique/club by espousing this you-might-get-kicked-out-of-our-shop attitude. I understand how that makes something exclusive, because that’s traditionally how exclusivity works. You can’t get something, so it drives demand. But, The Hundreds is all about making everyone who comes to one of their stores feel like a homie, and, implicitly, part of the brand. This flies in the face of how exclusivity works in my mind. Which model is more successful? Let’s say you’re starting your own brand…do you skew closer to The Hundreds model or Supreme’s?

Chris: Again, I think it always comes down to good design. One of my favorite companies, which represents a perfect merger of design and accessibility, is Ikea. It competes on many levels with much more expensive brands. That said, I’m not suggesting that you have to make really well designed t-shirts and sell them for $19 dollars a pop. Good design is an asset for a brand in that it gives the brand universal appeal to consumers, whether they’re plugged into a scene or not. People will appreciate a product if it’s well designed.

Stu: What do most buyers of streetwear look for? Often, it’s not about design and/or quality, it’s about buying into popular brands. That’s what makes it tough for new brands trying to establish themselves in streetwear. You have to be very strategic about product placement, how/where you market it, who’s wearing it, etc. – that’s how you become successful in streetwear. In higher end, contemporary fashion, you have a lot of more people walking into brick and mortar retailers so it becomes much more about quality, design, and fit, etc.

Yosef: Identifying who your core consumer is first is what it comes down to for me. That’s what’s going to dictate the direction of your brand. If your demo is younger, shirts that are almost like flags are more important. A lot of new rappers are following the precedent streetwear built, in that sense. But if you’re targeting an older and/or broader market, that’s really when subtle choices in product design start to distinguish successful brands. That said, it will always matter how plugged in your brand is to the scene.

Stu: Yup, that’s crucial to any brand across the board. If the right people are wearing your stuff, that’s the fastest way to grow. It’s always been that way.

Phil: So with all that said, what are you guys’ favorite brands?

Yosef: One that I really did like was Nom de Guerre. They did a great job with their whole presentation and look. Their price point was high enough that it gave them that feeling of exclusivity… you had to go into a basement off the street to find their shop. The recession hit them hard, but for a while, they were definitely doing it correctly. They started in the higher end of the streetwear space, and transitioned into contemporary menswear really successfully.

Stu: People talk about this one a lot, but rightfully so – how J. Crew turned around their menswear business in recent years is impressive. A critical part of what made their reinvention so successful is how they’ve tied themselves to really top notch brands like Barbour, Mr. Freedom and Belstaff in their physical retail locations. It really elevates the J. Crew brand.

Yosef: Uniqlo, and their parent company, Fast Retailing, is a good example of a brand that does their thing really well. Their lane is basics, and they just completely dominate that lane.

Chris: You know – the only other brand I can think of that is both really cool and all about making money is Apple.

Yosef: And I would even put Apple in its own category. At the end of the day, Ikea and Uniqlo use really competitive pricing as an advantage, whereas with Apple, you’re still paying a huge premium for their product, but customers still flock to their stores en masse.

Stu: Yeah, Apple is in its own league for sure. I rode that stock from $40, baby!

Chris: I remember the day Apple’s market cap crossed Microsoft’s, and you could HEAR all of the case studies being rewritten.

Phil: So the last question I have is, as people who have a strong grasp on both economics and fashion, what are some words of advice you have for people who want to start their own brands? I’d like you to pose your answers as if you were holding a meeting with said designers who are coming to you for seed money. What are you looking for if you were thinking about investing in a new fashion brand?

Yosef: If I was in that position, my question to any designer would be the most simple one: what sets you apart from the pack? It’s actually a very difficult question to convincingly answer. Also, I like brands that start out with a narrow focus and perfect a small range of products before expanding their portfolios.

Stu: I can’t emphasize this enough: a crucial thing that is too often overlooked is the production side of running a brand. If you miss a sales or delivery window for whatever reason, you’re hosed. Everyone else’s product is already on the shelves and you’ve got nothing. Knowing the right suppliers, being able to effectively manage your supply chain, how product gets to you, etc. is all important to any brand, not just a fashion company. Basically, the question is: who is your business guy?

Chris: Three things. It’s really important to think about how you are leveraging the internet to increase your distribution. It’s also critical to invest a lot of time, resources and energy into getting strong, meaningful branding early on. Lastly, putting a lot of thought into your business model is essential. A few companies that have impressed me in the fashion sphere all follow these points. There’s a pants company called Bonobos – they do a lot of their sales online. Warby Parker, which does glasses, is another brand. Shoedazzle is killing it. That business is making hundreds of millions of dollars a year by simply optimizing a unique business model.

Phil: Thanks for taking the time out to share you guys’ thoughts and insight today. Let’s go take a photo of you guys for the site, and then I’ll find old shots of you guys in JNCOs and Sean John to pair these with.

Editor’s Note: Phil Chang is a strategic creative at Wieden + Kennedy New York and a member of the agency’s multidisciplinary solutions team, Attack. Attack ensures that Wieden stays active as a creative participant in the culture of our beautiful city, while also freaking the good shit out for the agency’s primary clients. Prior to co-founding Attack with the design empire Grand Army (Larry Pipitone, Eric Collins, Joey Ellis) and the artist formerly known as Keiji, Phil worked at W + K NY as a brand strategist for Nike and Jordan Brand. You can follow Phil on both Twitter and Tumblr.